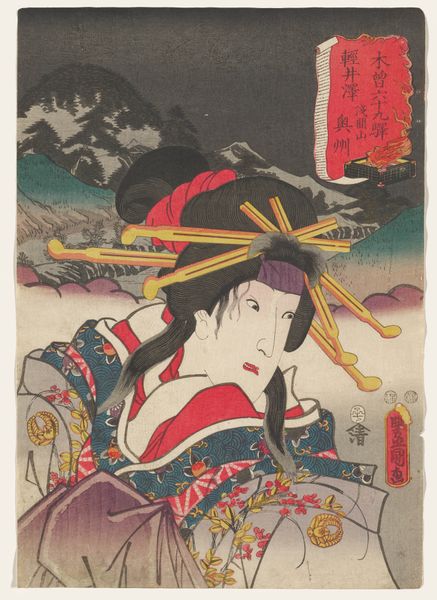

print, woodblock-print

#

portrait

# print

#

asian-art

#

ukiyo-e

#

figuration

#

woodblock-print

Dimensions: height 365 mm, width 253 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

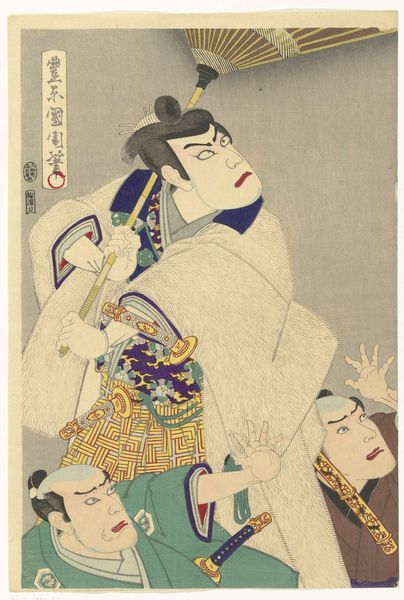

Editor: This intriguing woodblock print, "Iwai Kumesaburo III als Tamamo no Mae" by Utagawa Kunisada from 1862, shows a figure holding a fan. What stands out to me is the texture in the garment – it looks incredibly ornate. What's your take on this, seeing as it's now in the Rijksmuseum's collection? Curator: I'm immediately drawn to the materiality of the print itself, a *ukiyo-e*, a floating world picture, and the production process that brought it to life. Look at the registration of colors, the way each block must have been carved with meticulous care. It's a mass produced object, relatively speaking, intended for a specific social context. How do you think this print would have been consumed? Editor: Probably traded or sold to theater-goers as a souvenir. So, the accessibility of this print contrasts with the high status often associated with portraiture, doesn’t it? Curator: Exactly. Consider the labor involved: the artist, the block carver, the printer – a whole system of production. And let’s not forget the paper itself, its source, the pulping and pressing processes. It moves us away from this singular genius, towards a network of makers and distributors, embedded within a wider socio-economic structure of 19th century Japan. Editor: I hadn't considered the supply chains involved! The choice of wood, inks and dyes. It does change my perception entirely. Curator: It decenters the art object in favour of focusing our understanding on how art, like all objects, exists as a result of very real social processes and networks of making, trading and vending. Editor: That’s such a compelling way to see it, it reframes my idea of how ‘precious’ this type of artwork should be regarded. Thanks!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.