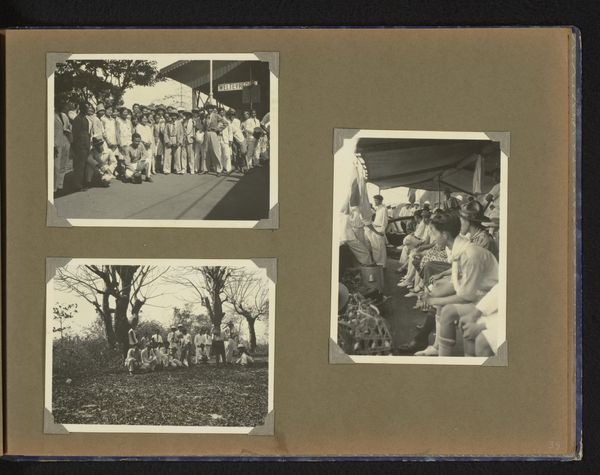

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

african-art

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

group-portraits

#

orientalism

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 190 mm, width 260 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

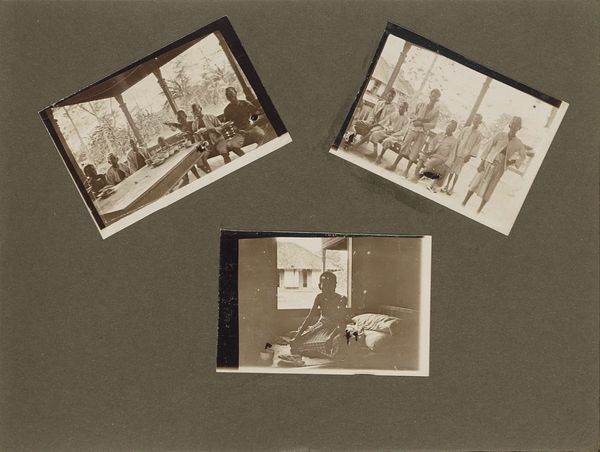

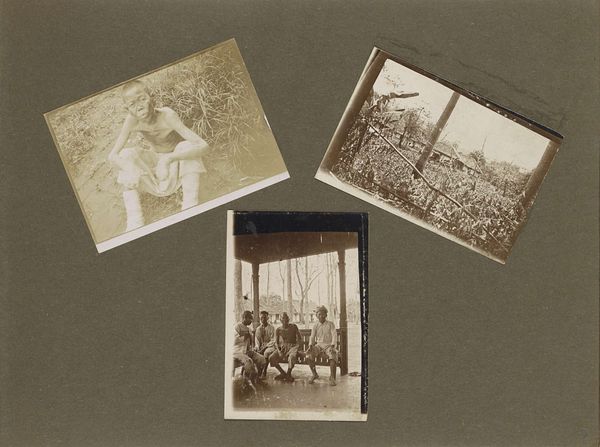

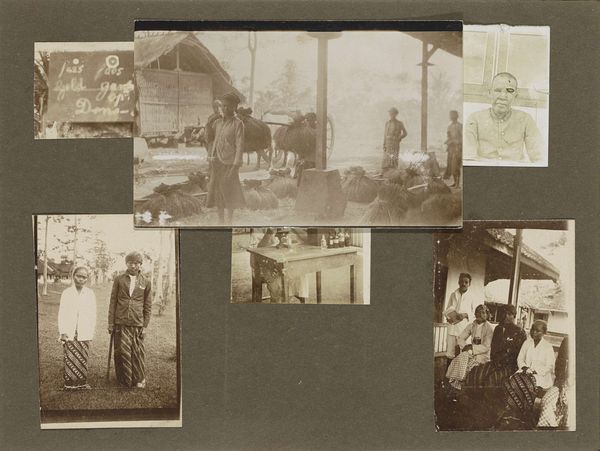

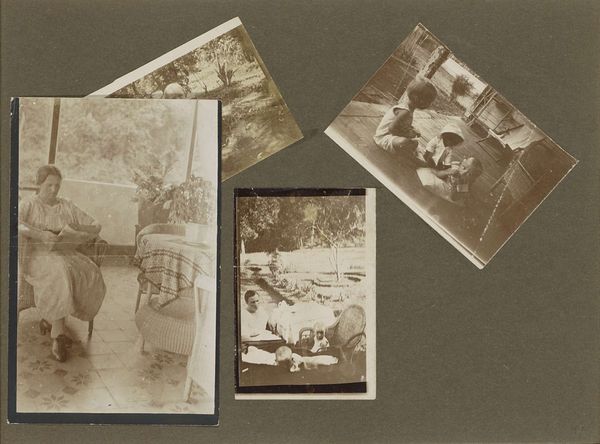

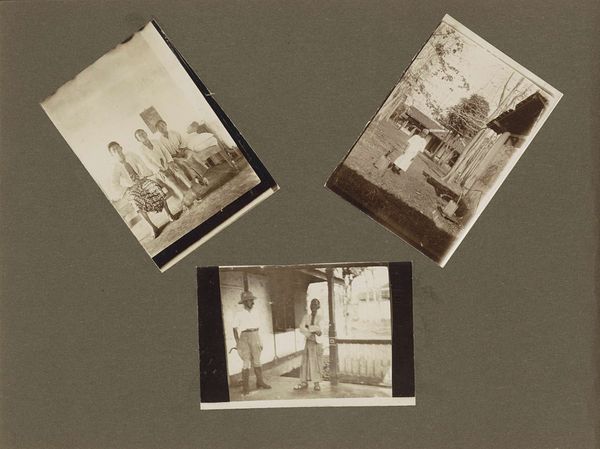

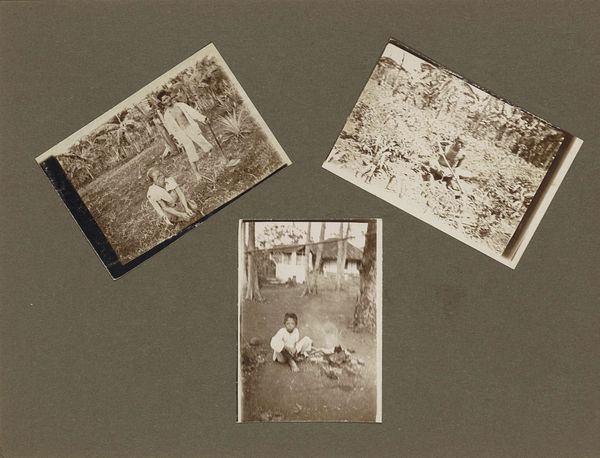

Curator: This is an anonymous gelatin-silver print from 1922, titled "Leprozenkolonie Danaradja: arts en personeel," which translates to "Lepers Colony Danaradja: doctor and personnel." It seems to capture a moment in time at a leper colony. What are your initial impressions? Editor: Stark. Isolated. I'm immediately struck by the clear visual hierarchy—the segregation, even—between the European medical staff and the local population affected by leprosy. Curator: That hierarchical composition definitely speaks to the colonial dynamic at play. Consider the visual language itself – who is being centered, whose gaze is privileged. We see three separate photographic compositions contained within a single frame, offering different perspectives on the colony. Each mini-narrative has the distinct whiff of Orientalism about it, especially as this photography style coincides with narratives around medicine, public health and colonialism. Editor: Exactly. The way the medical personnel are framed exudes control. Their position suggests authority, almost a surveying of the scene. How much was the photography used to serve colonial administration purposes by visually reinforcing the West’s self-portrayal as rational, civilized, progressive against an image of otherness and disarray? Curator: It is worth remembering that in addition to the political agenda that these types of photographic documents carried, they also often reveal a humanist concern, at least on the surface. Many public health campaigns were accompanied by similarly styled photos to build up support for these efforts. I am just not sure the way that “support” was achieved by casting some in the roles of the needy or “uncivilized.” Editor: But that so-called “concern” often serves as a guise for deeper ideological projects. The photo ends up normalizing existing racial, class and geopolitical hierarchies and justifying exploitation of resources and populations. How complicit are such images in perpetuating lasting legacies of oppression? Even if unconsciously, don’t they normalize the exploitation and degradation that become ingrained? Curator: I think we need to critically acknowledge and analyze their power, rather than simply viewing them as objective records. And we can do this while also grappling with more generous interpretations. The question remains—who do images of this type really serve? Editor: Well said. It forces us to reflect on the responsibilities of both image-makers and image-consumers.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.