![Wevende vrouwen ("Kalibafi a Sultanabad"), Sultanabad, Pakistan, Iran [?] by Antoine Sevruguin](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzL2M2NjFkNmFmLTUzNjktNDYzNC1hYWM3LTMyZTU5MjQyZDYwMC9jNjYxZDZhZi01MzY5LTQ2MzQtYWFjNy0zMmU1OTI0MmQ2MDBfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

Wevende vrouwen ("Kalibafi a Sultanabad"), Sultanabad, Pakistan, Iran [?] c. 1880 - 1910

0:00

0:00

photography

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

islamic-art

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 204 mm, width 155 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

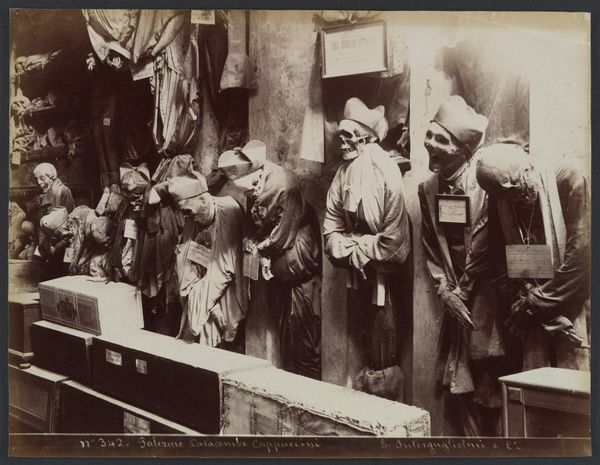

Curator: Let's explore this photograph attributed to Antoine Sevruguin, titled "Wevende vrouwen ('Kalibafi a Sultanabad'), Sultanabad, Pakistan, Iran [?]," dating from around 1880 to 1910. Editor: It's strikingly composed. The repetitive forms of the women and the hanging threads create a somber mood. The sepia tones definitely intensify the historical feel. Curator: Sevruguin was a photographer active in Iran during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This image, part of a larger body of work, presents an interesting example of Orientalist photography, capturing scenes of daily life and labor. Think about how images like this were circulated and consumed, often reinforcing Western perceptions of the East. Editor: Focusing on their process of weaving, it brings up questions about skill, the domestic sphere, and probably exploitation. The women are weaving what is suggested in the title is Kalibafi a Sultanabad which is a type of rug. This photograph shows them at their place of labour, how do we begin to measure the social value of their textile production versus what they were probably paid for it? Curator: Absolutely. The image, while seemingly ethnographic, is staged, perhaps constructed for a Western audience eager for exotic representations. We need to question the photographer's intentions and the power dynamics at play. Are we looking at a romanticized vision, or a truthful depiction? What agency did these women have in this portrayal of their lives? How does it reflect gendered roles and labor within the societal framework of the time? Editor: It almost seems that their individual identities become part of the uniformity that is involved in production. Look at the weaving process. So many identical threads placed together to create this one piece. In this, are these women's identities being considered through the Orientalist lens, too? Curator: Indeed. By interrogating the photograph through a postcolonial lens, we can critically assess how such imagery shaped perceptions and reinforced power structures. Whose story is truly being told, and who benefits from its telling? Editor: Considering the sheer labor these women pour into these materials, one must imagine that it may have given them autonomy to earn money, providing a glimpse into the complexities of gender, class, and commerce in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Curator: Yes, the photograph's stark imagery opens a necessary dialogue about the gaze, labor, representation, and how we understand identity and power relations across cultures. Editor: And that’s why I think this examination into labor makes you see that we need to confront, respect, and re-assess historical representation from the margins.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.