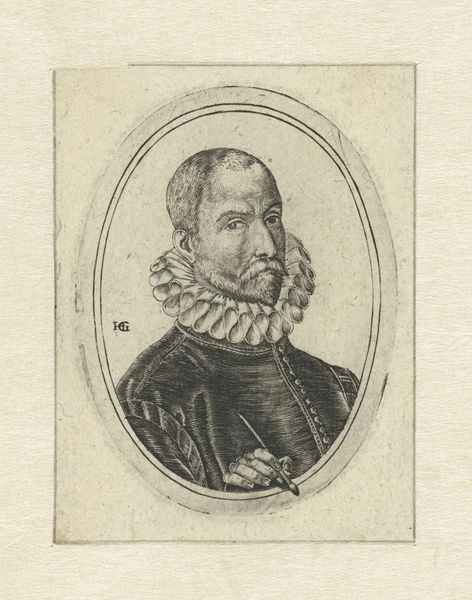

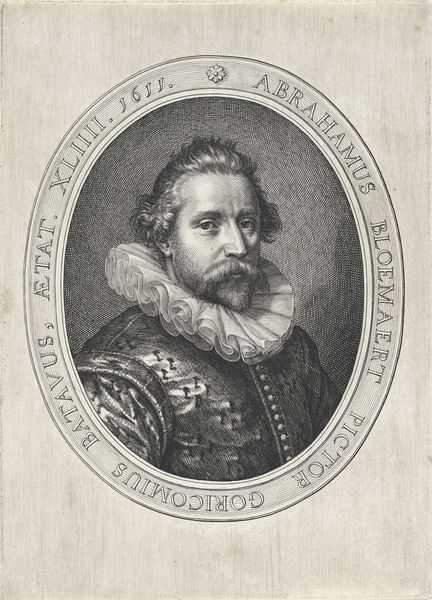

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 163 mm, width 106 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: We're looking at a print entitled "Portret van Marcus Gheeraerts de Jonge," an engraving dating back to 1644. It is currently housed in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Intricate and somber. The tightly packed lines creating the shading certainly capture a sense of weighty formality. And that ruff! The sheer detail is remarkable for an engraving. Curator: Wenceslaus Hollar, the artist, clearly intended to convey status. Gheeraerts was, after all, a prominent painter, having served under Elizabeth and Anne. Note how the inscription beneath the portrait explicitly lays out his illustrious connections and artistic heritage. This print then, served to further cement Gheeraerts' legacy and professional standing within a very particular social hierarchy. Editor: The oval frame is interesting—how it contains but also presents the sitter. I’m also intrigued by how Hollar uses the hatching and cross-hatching to define the planes of Gheeraerts’ face, especially around the eyes. There’s an almost melancholic expression there. Do you see that as well? Curator: Indeed, though I would venture that any sense of melancholy is rooted in the circumstances of its production and purpose: an exercise in preserving reputation through controlled visual media in 17th century London. Think about the engraver's skill and the process itself, reproducing images, ensuring the work found its audience and played its intended role in the art market and social fabric of the time. Editor: But consider how the stark contrast between light and shadow adds a depth that belies its being merely representational. This use of chiaroscuro lends a real drama and emotional weight to the image. And notice how, formally, the lines converge toward his face. Curator: What strikes me most, beyond the aesthetic considerations, is the meticulous labor that went into its making. And it is crucial to realize that, ultimately, prints were relatively democratic objects compared to paintings; accessible to a wider audience, thereby allowing Gheeraerts's image, and consequently his status, to circulate. Editor: I'm left considering how Hollar was able to breathe such palpable life into this image, and how viewers throughout the centuries are likely to connect with it on an emotional level, not just a cerebral one. Curator: For me, it sparks reflection on the system of patronage and production in early modern Europe. A dance of labor, material, and marketing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.