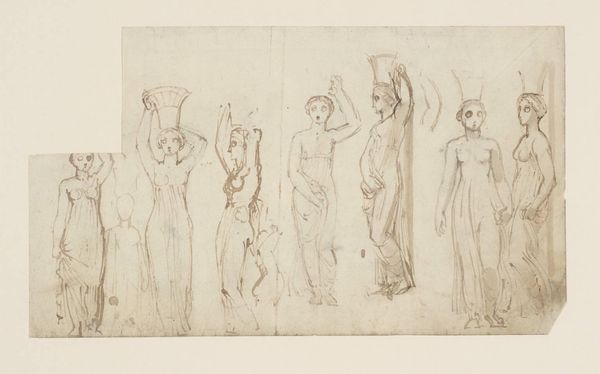

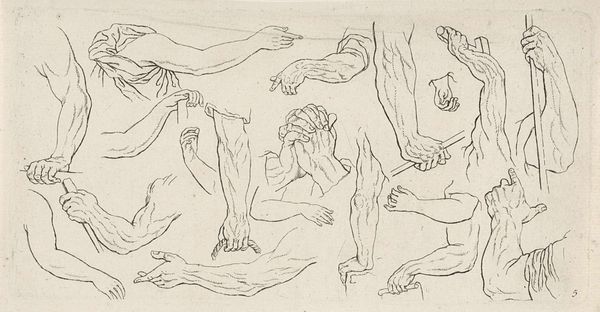

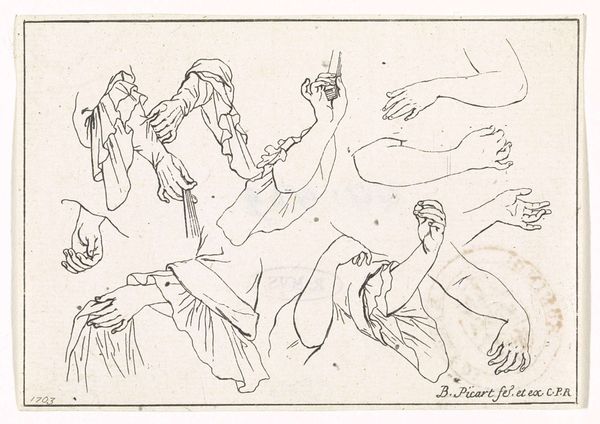

drawing, paper, ink

#

portrait

#

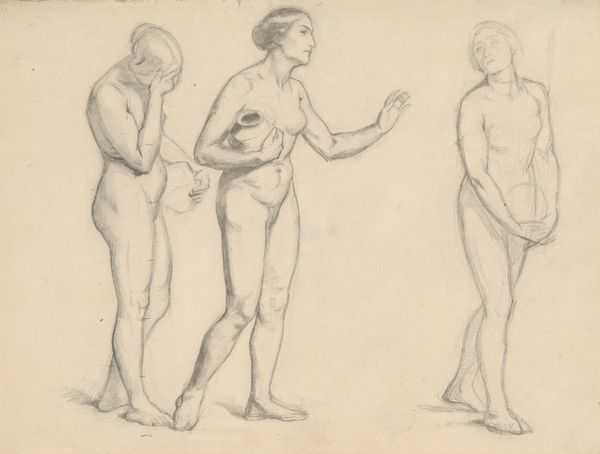

drawing

#

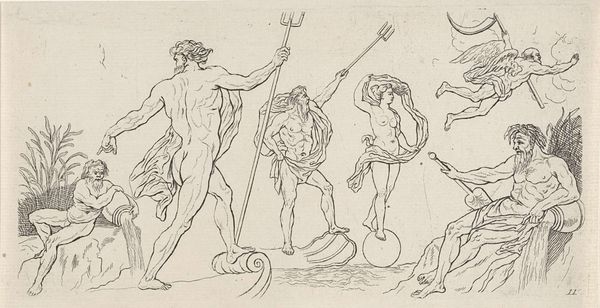

baroque

#

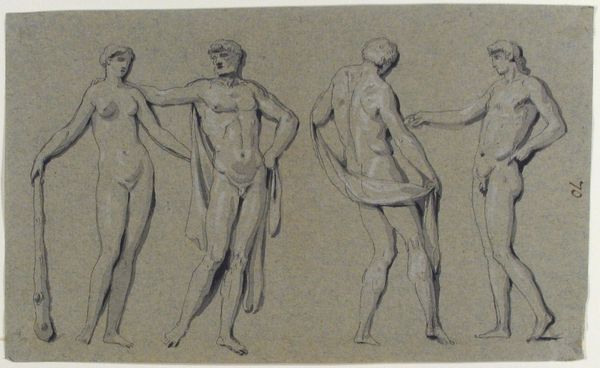

classical-realism

#

figuration

#

paper

#

form

#

ink

#

line

#

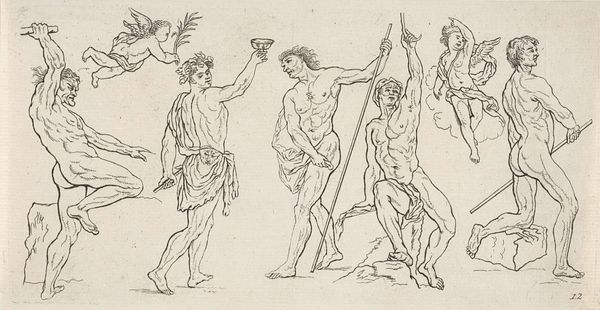

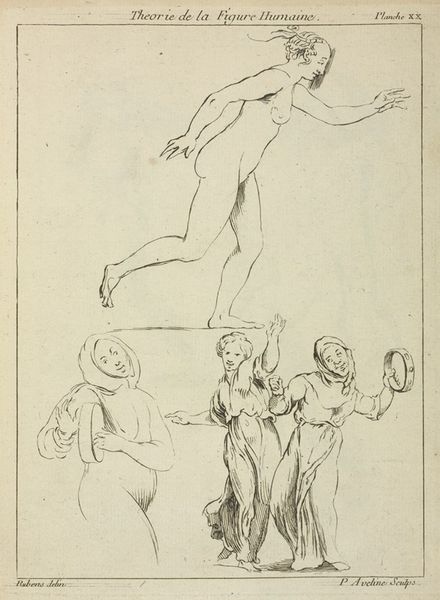

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

nude

Dimensions: height 94 mm, width 193 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

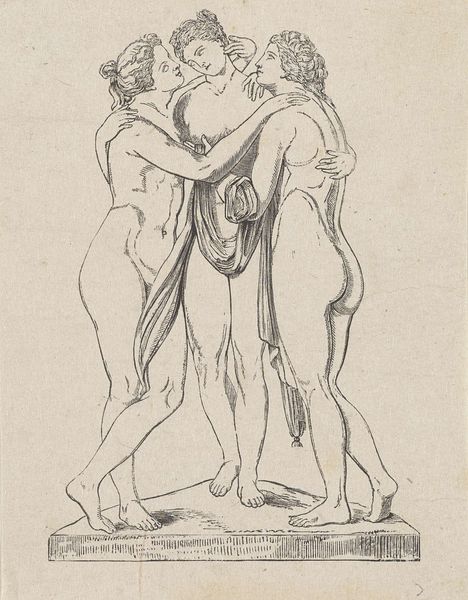

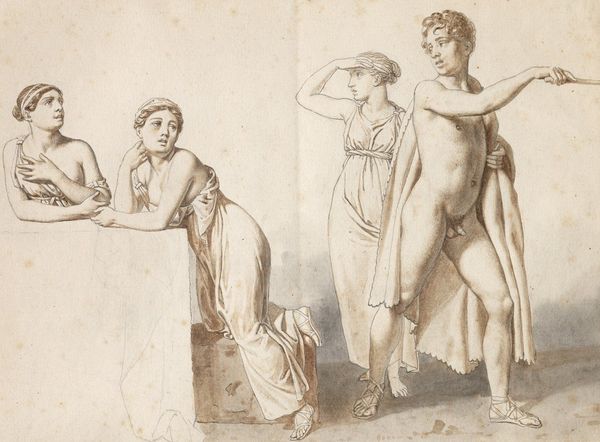

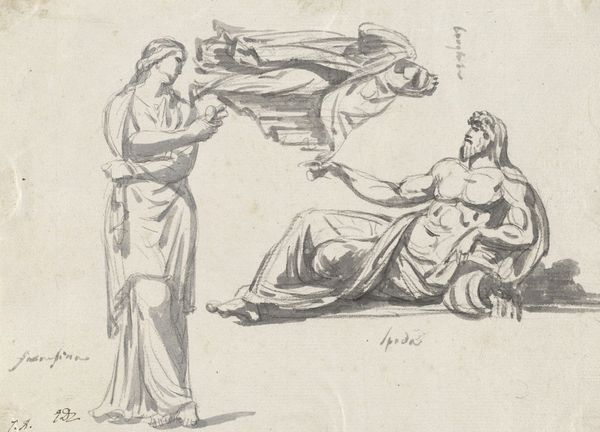

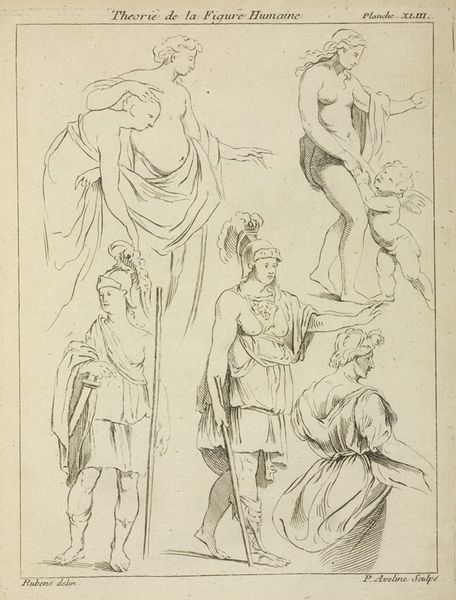

Editor: We’re looking at “Studie van menselijke bovenlichamen,” or "Study of Human Upper Bodies," created between 1710 and 1767 by Leonard Schenk. It’s a pen and ink drawing on paper, currently held at the Rijksmuseum. What strikes me is the almost sculptural quality achieved with just line work, particularly the academic rendering of the human form. How do you interpret this work? Curator: It’s fascinating how this drawing reflects the evolving role of art academies in the 18th century. We see Schenk engaging with classical ideals – those heroic nudes hark back to antiquity, right? But it’s not just imitation. Notice how they are studies; they're exercises meant to train artists, to instill a visual language tied to power and idealised forms. Consider the social implications: who had access to such training, and whose bodies were deemed worthy of representation? Editor: So, this wasn’t necessarily intended as a public artwork, more of an internal educational tool that reflected the values of the art world at the time? Curator: Exactly. These academies acted as gatekeepers. They were powerful institutions shaping artistic taste and defining what "good" art should be. Think about the patron class then - nobility, wealthy merchants - they consumed art that reinforced their social standing and cultural authority. And how do you think this method of learning, of idealizing, influenced public perceptions of beauty and power? Editor: It’s almost like these drawings were subtly shaping a visual ideology. By standardising representations of the body, they reinforced specific ideas about beauty, class, and even gender. It's much more layered than just technical skill. Curator: Precisely! And seeing it this way changes how we understand its significance. It becomes a window into the socio-political dynamics of art production and consumption. Editor: I see it now. It makes me think differently about how institutions and power structures impact art. Thanks for clarifying that. Curator: Indeed, art never exists in a vacuum; it’s constantly shaped by—and shapes—the society around it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.