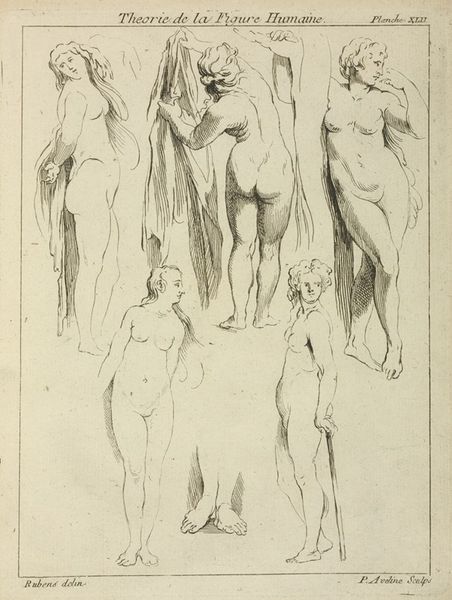

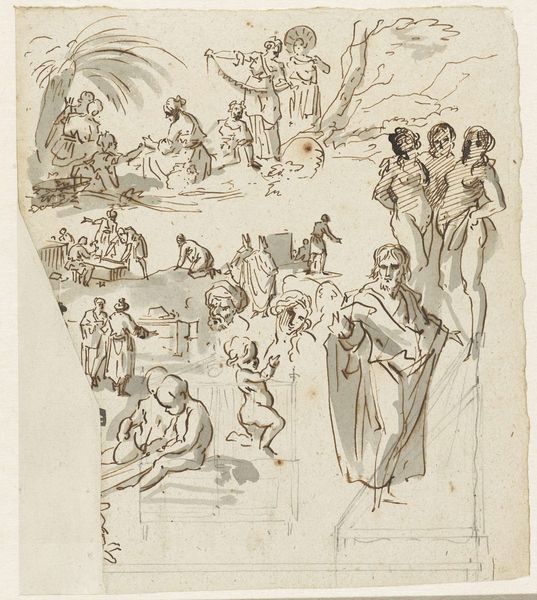

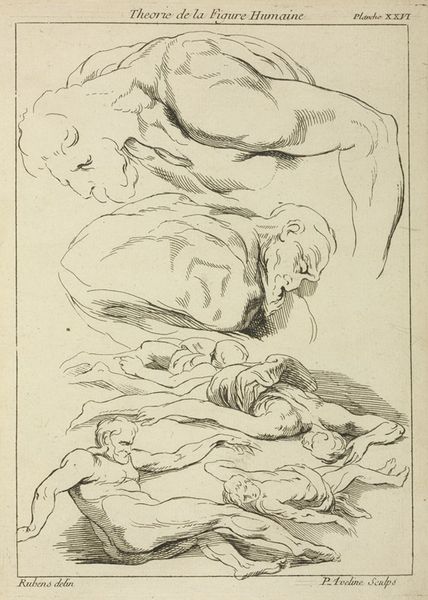

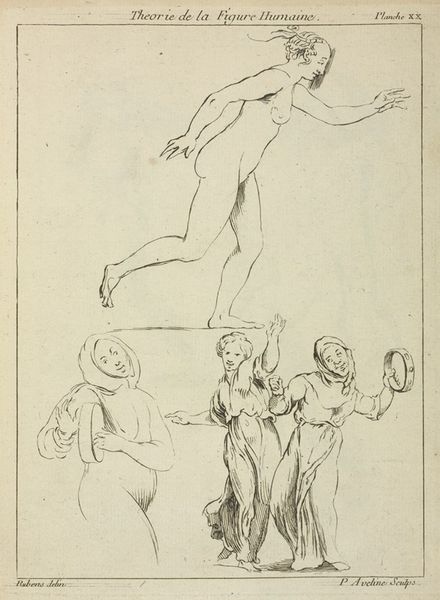

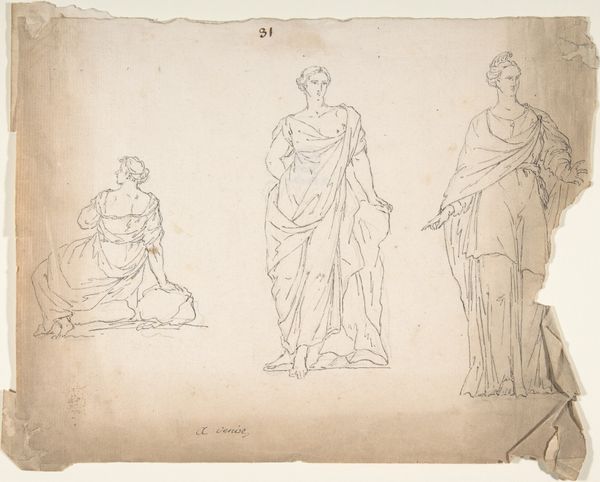

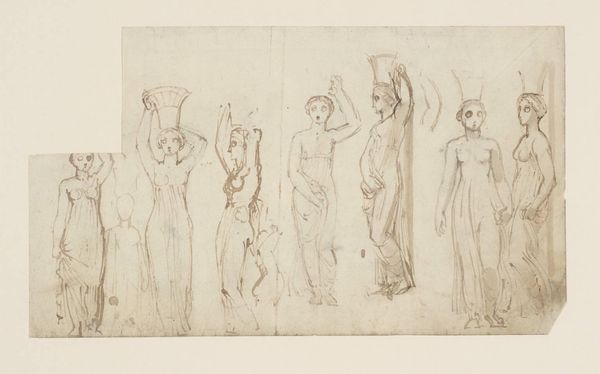

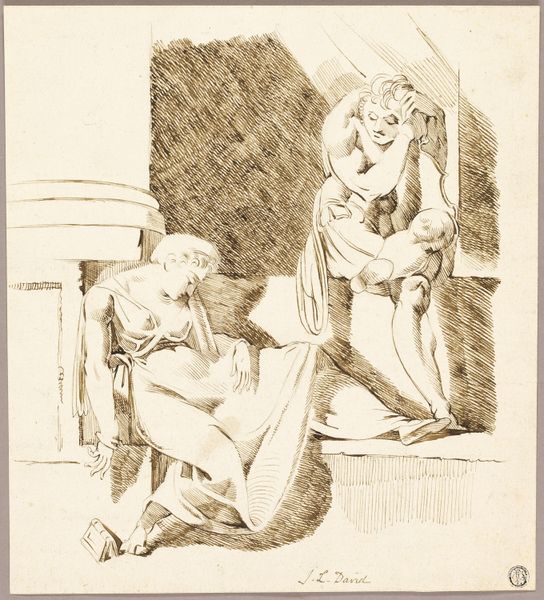

Various figures including Roman soldiers, and partially draped male and female nudes

0:00

0:00

drawing, paper, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

pencil sketch

#

classical-realism

#

figuration

#

paper

#

romanesque

#

ink

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

nude

#

engraving

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

Editor: This drawing, "Various figures including Roman soldiers, and partially draped male and female nudes," is attributed to Peter Paul Rubens. It seems to be an ink and pencil sketch on paper, perhaps a study for a larger history painting? It’s striking how dynamic all the figures are, even though it’s just a sketch. How do you interpret this work? Curator: I see this not just as a preparatory sketch but as a powerful assertion of classical ideals during the Baroque period. Consider the male nudes alongside Roman soldiers—aren’t we implicitly examining constructions of masculinity, power, and the male gaze prevalent at the time? How does this ideal contrast with lived experiences, especially for marginalized bodies? Editor: So, it’s not just about classical aesthetics, but also about power dynamics? Curator: Precisely. Rubens, celebrated as he was, was operating within a very specific social framework. These figures represent a kind of idealized European masculinity, a standard that automatically excludes or marginalizes anyone who doesn't fit that mold. Notice how the female figures are depicted—often partially nude, passively positioned relative to the active male figures. How does that inform our reading? Editor: That makes me think about how academic art reinforced particular standards for bodies and representation, creating a hierarchy. Curator: Exactly. Art isn't created in a vacuum. This drawing prompts critical questions about whose bodies are valorized, and at whose expense. By examining the social and historical context, we can decode how art actively participates in constructing identities and power relations. Editor: I’ve definitely gained a broader perspective. It’s important to examine artworks from multiple angles. Thank you! Curator: Absolutely. Engaging with art critically empowers us to challenge those historical power structures, leading to a more inclusive art world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.