painting, sculpture, enamel

#

narrative-art

#

painting

#

sculpture

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

sculpture

#

enamel

#

history-painting

#

decorative-art

#

portrait art

#

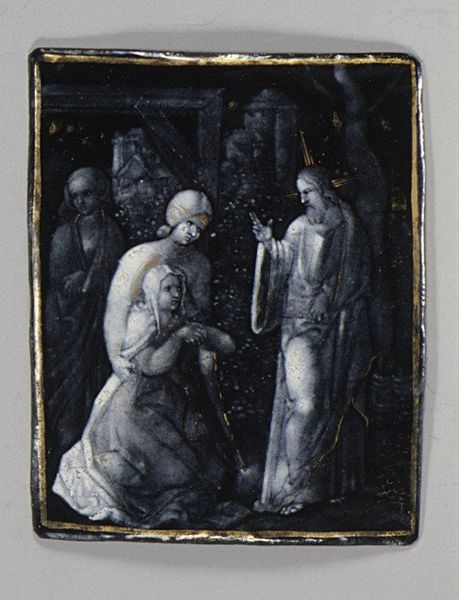

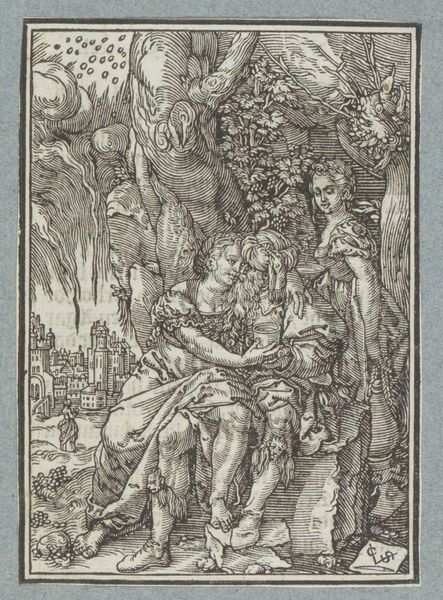

christ

Dimensions: 2 3/4 x 2 1/4 in. (7 x 5.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Let's take a closer look at "The Betrayal," one of a series of seven enamel plaques created by Jean II Pénauld between 1530 and 1565. It currently resides here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is the dramatic chiaroscuro. The figures almost seem to emerge from a smoky, black background, illuminated by an unseen light source. It creates a sense of immediacy, of witnessing a clandestine event. Curator: Absolutely, and this enamel work represents the burgeoning industry serving courtly elites who had developed interest in lavish objects and decorative arts. The contrast certainly enhances the emotional intensity inherent in this pivotal moment from the Gospels. Editor: The composition, while crowded, really draws your eye to the central figures of Christ and Judas. Their embrace, or rather, Judas’ deceptive kiss, is rendered with meticulous detail. The artist masterfully captured the tense facial expressions too. Curator: Indeed. Notice also how Pénauld strategically places that figure with the rope on the edge. It seems Pénauld may be alluding to Christ's role as sacrifice and a figure that represents power of resistance to the law. The crowd also looms large. Editor: Speaking of the background figures, there's almost a frenetic energy to their poses. Their expressions aren’t individualized which is curious. The formal arrangement is not just representational but loaded. Curator: Agreed. One should recall, of course, the widespread social instability of the Renaissance during which the authority of Catholic church was being aggressively challenged and thus paintings of a familiar subject was highly charged. It offered a site through which the artist engages the anxieties of the day. Editor: It’s amazing how a work of this size, crafted using the enamel technique, manages to convey such palpable tension and foreboding. The cool grays heighten that drama effectively. Curator: It really demonstrates how faith could also function as propaganda for powerful, elite families, particularly at a volatile historical moment. Editor: Reflecting on it now, I'm struck by how Pénauld turned an object designed for close looking into a space for contemplation. Curator: And hopefully, we've shown it's more than just religious art; it reflects wider social anxieties of the 16th century.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.