Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

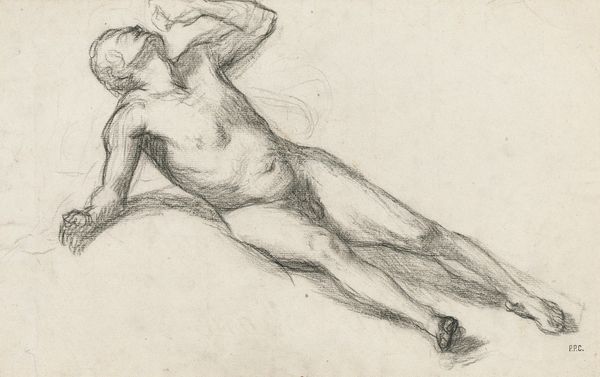

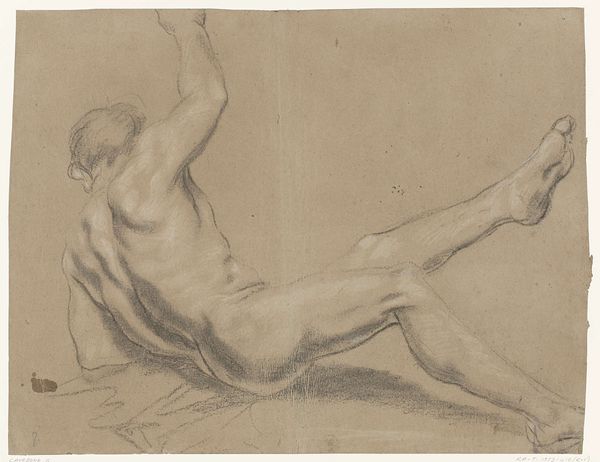

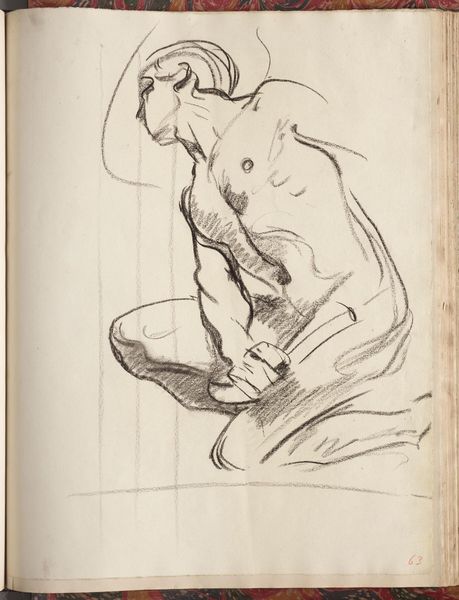

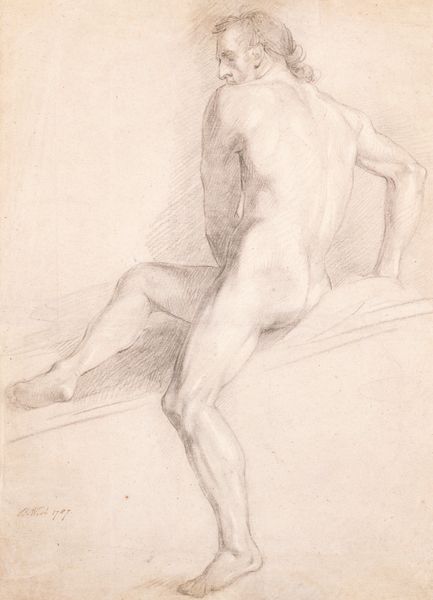

Editor: This is Paul Cézanne's "Study of Puget's 'Hercules Resting'," dating from around 1879. It’s a pencil drawing, and what strikes me most is how classical it feels, despite Cézanne's later innovations. What do you see in this piece? Curator: What I see is Cézanne engaging with the academic traditions of his time, grappling with the canon itself. Consider the implications of a post-Impressionist artist studying a Baroque sculpture, Puget’s Hercules. What statement might Cézanne be making about artistic lineage and the role of the academy? Editor: I suppose it shows Cézanne building on the past, rather than simply rejecting it. Curator: Precisely. Think about the public function of art in the late 19th century. Academic art was promoted by institutions as a vehicle for moral and civic values. Cézanne's study challenges this. Is he merely copying, or is he re-evaluating the heroic ideal embodied by Hercules? And, crucially, how does the medium – a quick, unassuming pencil sketch – affect our reading of this iconic figure? Editor: So, the choice of a quick sketch disrupts the established ideal? It becomes more personal, less about the grand narrative. Curator: Yes. The “unfinished” quality questions the authority that academic art tried to project. Instead of a polished, definitive statement, we get a glimpse into Cézanne’s artistic process, his own negotiations with art history and his own cultural and historical position. Editor: I hadn't considered the political implications of something that seems so simple. It's interesting how a drawing can be more than just a drawing; it can be a statement! Curator: Absolutely. Considering art within its institutional and historical framework really deepens our understanding and expands how we view not only art’s purposes, but its potential to affect the societies that display it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.