Coaching Horn, from the Musical Instruments series (N82) for Duke brand cigarettes 1888

0:00

0:00

drawing, print

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

art-nouveau

# print

#

caricature

#

musical-instrument

Dimensions: Sheet: 2 3/4 x 1 1/2 in. (7 x 3.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

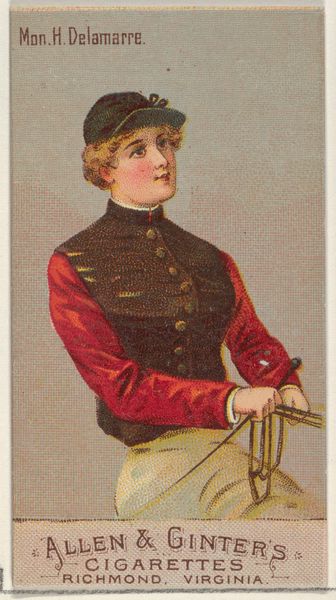

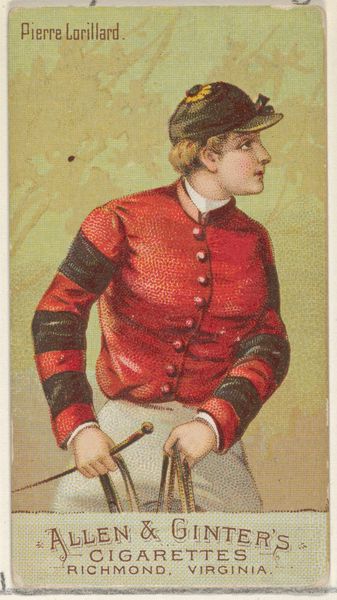

Curator: This is a trade card from 1888, titled "Coaching Horn," part of the Musical Instruments series (N82) distributed to promote Duke brand cigarettes. Editor: Immediately, I’m struck by the strange contrast. There's this detailed portrait, almost doll-like, rendered on what’s essentially a small advertisement. It feels inherently…commercial, and yet quite refined in its production. Curator: Absolutely. The "coaching horn" itself would have been used to signal directions and timings to a horse-drawn carriage. The young woman depicted is essentially advertising both the instrument's purpose and, implicitly, the luxury associated with such conveyance, as well as, of course, the cigarettes themselves. Consider that cigarette cards like these functioned as miniature artworks in everyday circulation, building brand identity, and circulating cultural values. The attire seems almost military in style but in its precise elegance signals wealth and control, like the capability of being in charge. Editor: It is telling, the extent they go to using various visual references as an indication of quality in the final, purchased product. The print quality for something meant to be disposable seems surprisingly high. What inks and paper stock were common at this point for mass production, and how did that affect image-making? Curator: By the late 19th century, advancements in printing techniques made mass-produced color images much more affordable and readily available. These chromolithographic prints made images with remarkable clarity for this type of production and circulation. It reflects, in part, the ambition of brands like Duke to elevate the status of what we would nowadays regard as commonplace advertising through these artworks and a whole host of giveaway objects. Editor: Thinking about materiality, the sheen of the horn mimics a gilded opulence that feels deliberately manipulative now that we’re so far removed. A modern advertisement can communicate its brand more easily, but at that time, the object itself had to sell its brand with as many material symbols as possible. I do think it succeeds here; I am strangely drawn in by its construction. Curator: Ultimately, it demonstrates the subtle power of cultural associations—linking an enjoyable luxury like cigarettes to notions of refinement, control, and a well-appointed lifestyle through layered symbols. It speaks to the long and enduring nature of symbolic manipulation. Editor: Seeing this level of material culture contextualized this way offers new insights into both art and consumer culture, prompting us to rethink art history's reliance on object categories and the separation between high and low forms of expression.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.