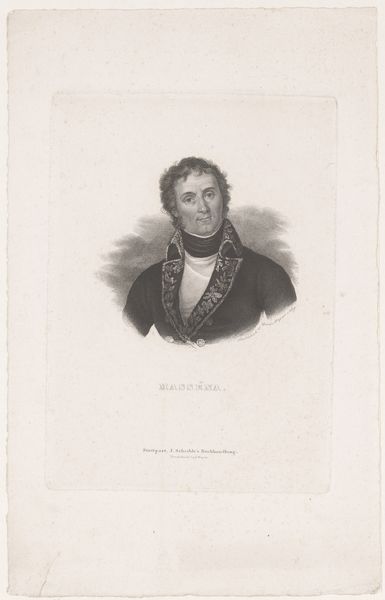

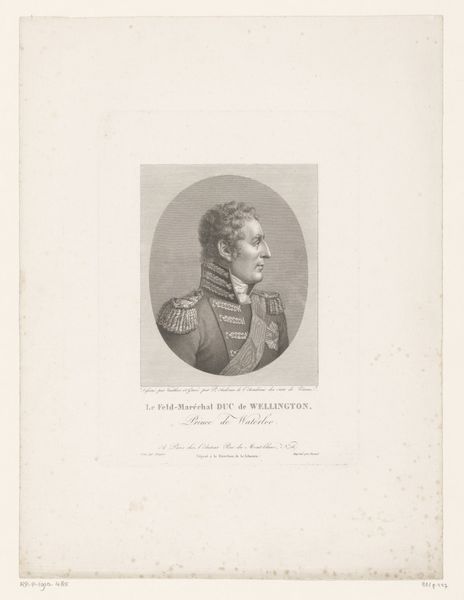

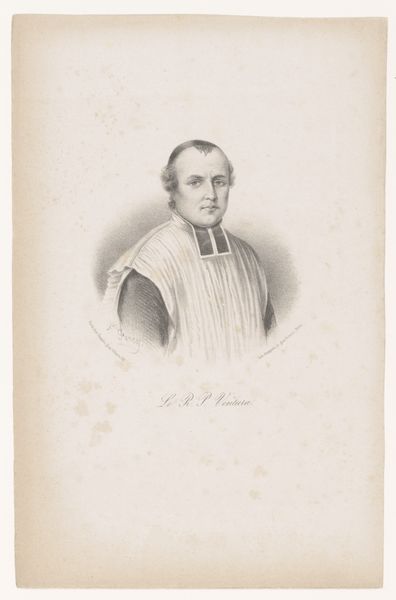

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

old engraving style

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 226 mm, width 141 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Up next, we have a stately "Portret van Paul Grenier," an engraving dating from 1820-1821 by Ambroise Tardieu. It's a lovely example of Neoclassical portraiture. Editor: The precision is striking. Look at that delicate hatching—you can almost feel the texture of his velvet collar. It’s an image that screams “bourgeois comfort,” which raises the question: who benefitted, materially, from its production? Curator: Well, engraving was a key process for disseminating images back then. Think of it as the printing press meets portraiture. This particular example portrays Paul Grenier, a deputy. The portrait immortalizes him but it also acts as political capital. Editor: Right, we see it not only commemorates the individual but communicates power. And what about the physical labour? Engraving involved highly skilled artisans using specialized tools to etch designs onto metal plates, a craft embedded in workshops, apprenticeships, and economic hierarchies. It's a whole material world implied within this "refined" portrait. Curator: Absolutely, and don’t forget the influence of Neoclassicism itself—a movement rooted in ideas of order, reason, and civic virtue. Grenier, as depicted, embodies those ideals. See how his gaze is direct, his posture composed. It’s a statement about his character as a leader. The print becomes another medium to display political and social ideologies. Editor: The man embodies stability— but isn’t there a tension? A print intended for mass distribution paradoxically depicts an elite figure. The print attempts to monumentalize political power by flattening material and class divides that produced it, isn’t it? I mean, isn't it weird how his clothes look newer and better crafted than mine will ever be? Curator: A valid point. Although made accessible, it clearly affirms Grenier’s social standing in contrast to all the artisans involved in creating the print. So the medium becomes quite a symbol of what you could buy into back then. A visual paradox of its time, maybe. Editor: Maybe "paradox" sums it up perfectly, yes. I mean, there's the portrait staring back at us now, years after its original engraving; both subject and object, bound by materials, power, and process. Curator: Indeed! I now see his story much clearer.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.