print, textile, engraving

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

textile

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 140 mm, width 190 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

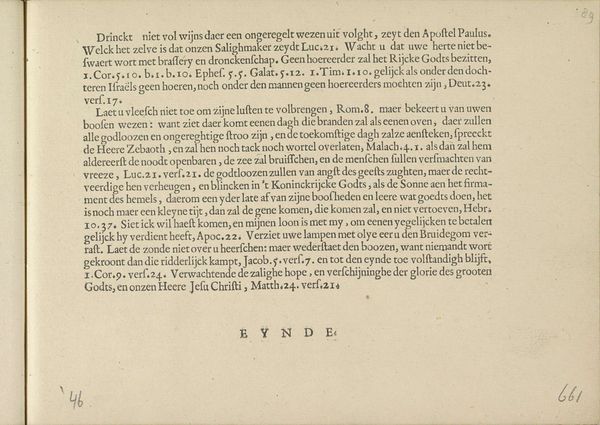

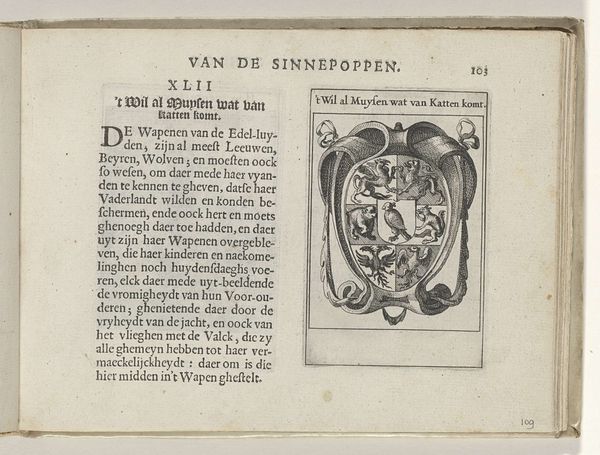

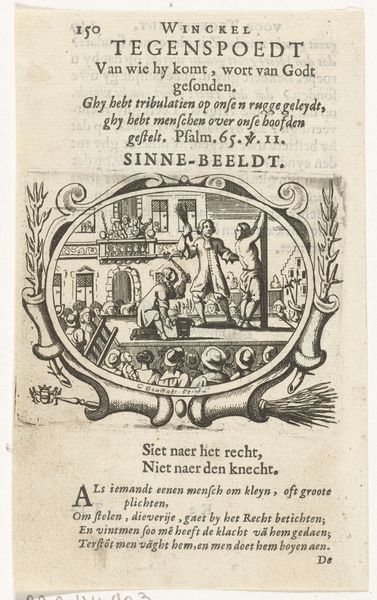

Curator: Today, we're looking at "Nederlandstalig voorwoord, pagina 1," or "Dutch Preface, page 1," an engraving created in 1641 by Crispijn van de Passe the Younger. It’s currently held in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first impression? It's a dense page of tightly packed text. Very serious. Austere, even. The high contrast of the engraving lends a severity to the whole thing. Curator: Yes, the visual weight is certainly in the details. Observe the decorative initial 'D' which depicts classical figures interwoven with foliage. How does that stylistic choice contribute to the reading experience? Editor: Well, text functions as textile. The dense rows speak to a certain period aesthetic that found delight in surface, decoration, and pattern. Consider, though, that in terms of broader societal readings, this text makes claims about gender. Specifically, Crispijn invokes the Poet Ovid, suggesting, through fables, that loose women mislead virtuous men and, furthermore, are a catalyst for male jealousy. Curator: An interesting reading. I was going to mention how the texture achieved by the engraving highlights the material reality of the book. The page becomes an object, rather than merely a carrier of information. Semiotically, one could examine how the language, although unfamiliar to a modern speaker, signals authority through its visual presentation and calligraphic flourish. Editor: True, and let's not overlook the intended audience. This preface likely aimed at a privileged, literate segment of Dutch society, reinforcing existing power dynamics and moral frameworks of its time. Curator: A worthwhile addition. I think examining the visual strategies that elevate printed text as art opens up some interesting dialogues about book production and information dissemination during the Dutch Golden Age. Editor: Indeed, and through examining the content of such a piece we also reveal its place within discourses of gender, morality, and class circulating then—and perhaps even now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.