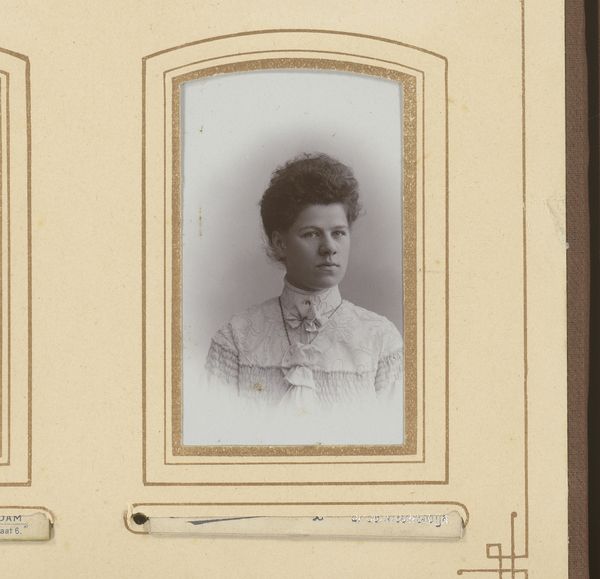

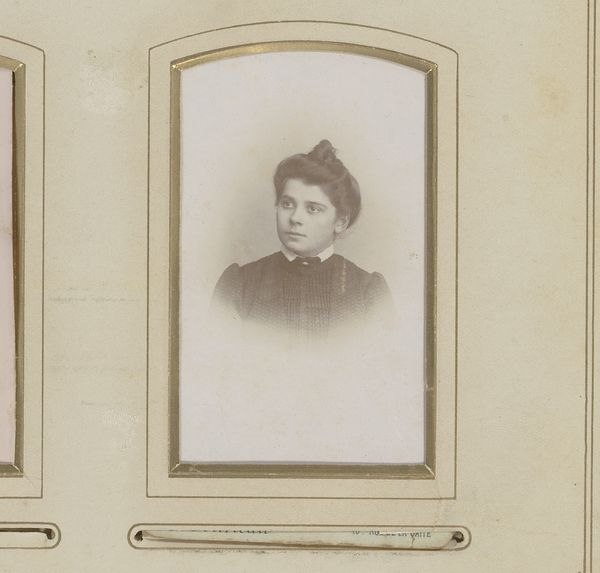

photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

photography

#

watercolor

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 80 mm, width 50 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is "Portret van een vrouw" – Portrait of a Woman – by Atelier Herz, dating from somewhere between 1892 and 1910. It’s an albumen print, and there’s a real sense of quiet dignity about the subject. What stands out to you when you look at this portrait? Curator: I’m immediately struck by the power dynamics inherent in portraiture of this era. Consider the sitter's clothing: the high collar, the restrained embellishments. These elements, while seemingly decorative, were potent symbols of class and societal expectation, essentially functioning as a kind of uniform. Do you think the artist's intention was to capture the individual or to reinforce a specific social ideal? Editor: That's a great point. I hadn't considered the clothing as a social signifier so directly. It makes me wonder about her agency. Did she choose to present herself this way, or was she compelled by societal pressures? Curator: Exactly. And how much did Atelier Herz, as photographers, influence or even dictate the pose, the lighting, the entire presentation? Photography in this period wasn’t just about capturing an image, it was about constructing an identity, one often aligned with bourgeois values. Where do we locate the ‘truth’ of this woman, within these layers of representation? Editor: It feels like peeling back layers of an onion – or in this case, lace! I'm seeing now how the photograph itself becomes a stage for performing identity. Curator: Precisely! And think about who had access to these portraits and who didn’t. Photography became a powerful tool for preserving and solidifying a certain kind of historical narrative, one often excluding marginalized voices. How do we challenge that narrative today when engaging with these historical images? Editor: I’m seeing that understanding the historical context allows us to question the image, rather than accepting it at face value. This makes me consider portraiture in a new, critical way. Curator: And that’s exactly the point, isn't it? To continually question, to unearth the stories beneath the surface and ask, "Whose story is being told, and whose is being left out?"

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.