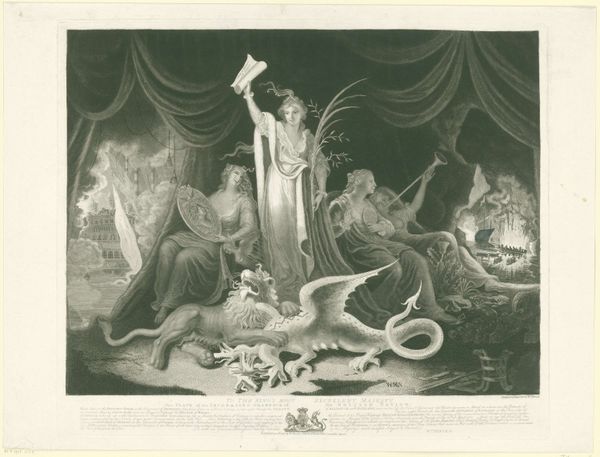

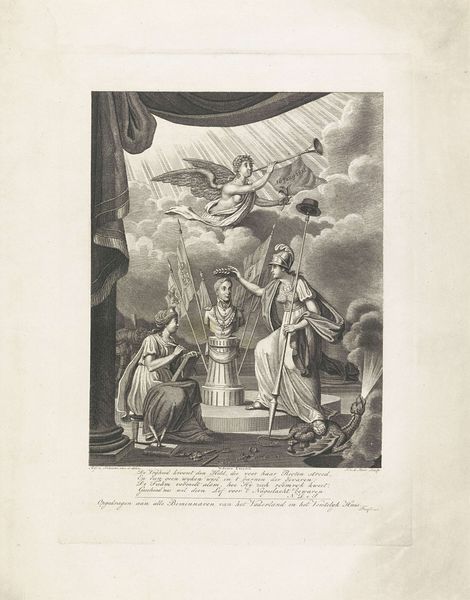

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

#

allegory

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

form

#

19th century

#

line

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 409 mm, width 322 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

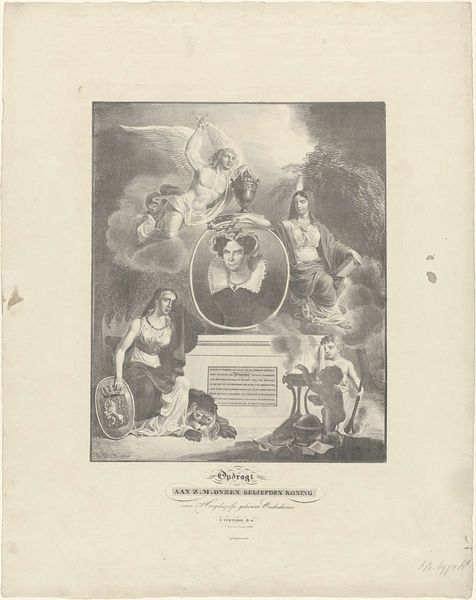

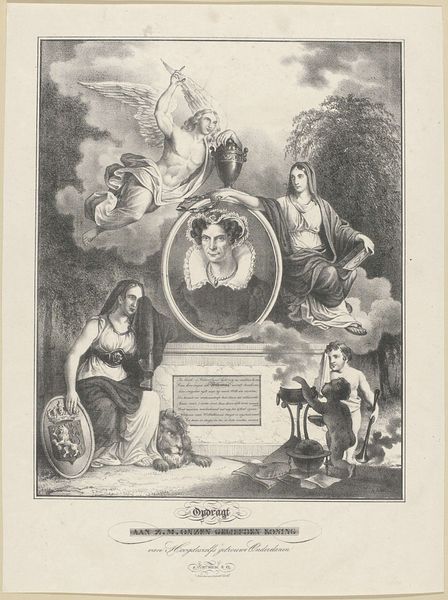

Curator: This engraving, dating from 1837-1839, is an allegorical monument dedicated to Wilhelmina of Prussia. The artist is Johannes Steyn. Editor: My first thought is, wow, what a layered composition! There’s a central portrait, framed by these rather grandiose allegorical figures… feels very symbolic, very staged. Like a dream unfolding from memory. Curator: It is staged, absolutely. Neoclassicism often draws on these heavily staged allegories. Note the lion, a national symbol, reclining passively. A winged figure of fame hovers above, holding what seems to be an urn. The other figures seem to be representing traits or accomplishments associated with Wilhelmina. This wasn’t just a portrait; it was an exercise in constructing her public persona after death. Editor: A posthumous image makeover, you might say! And there’s almost a kind of wistful melancholy hanging over it, even with all that grandeur. It makes me think about how we choose to remember people, especially those in power. Was Wilhelmina really like this picture, or is it a carefully curated ideal? Curator: Wilhelmina was Queen consort of the Netherlands, wife of William I. The print likely served as both a memorial and a piece of political communication. She died in 1837 and these prints circulated afterwards, bolstering her husband’s legitimacy and framing her legacy in a particularly favourable light. Prints like this were powerful tools for shaping public perception. Editor: So, a political pamphlet in mourning drag? The cherub kind of hints at that: he is putting out a flame on an altar, while some heavy books lay around; perhaps a suggestion she was a queen of science and wisdom, extinguished way too soon. But looking beyond that, it’s tempting to see this image also as a mirror of our own attempts at preserving a past which is eternally gone and irretrievable. What is the story we tell and what is really lost in translation? Curator: Precisely. Art like this makes the historical and cultural context incredibly visible. Editor: Agreed. Makes you want to dig deeper, beyond the image, to find out more about the real Wilhelmina.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.