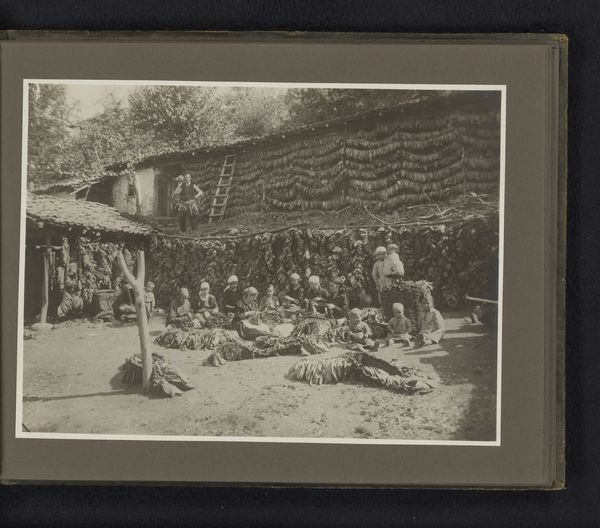

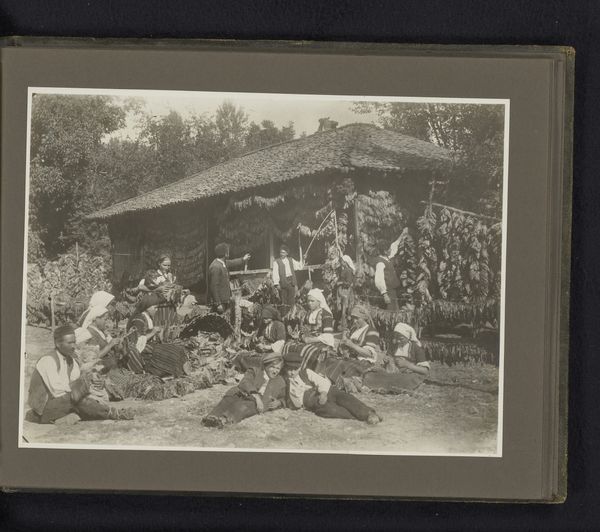

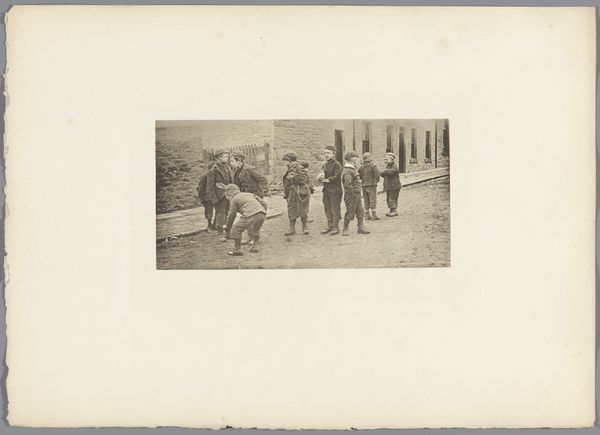

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

landscape

#

photography

#

group-portraits

#

orientalism

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 120 mm, width 169 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This striking gelatin silver print, created in 1894 by Christiaan Johan Neeb, is titled "Goesti te midden van zittende mannen." It seems to portray a leader amidst his followers in what looks like a constructed landscape. What's your immediate reaction to it? Editor: A sense of profound imbalance, actually. There’s such a studied contrast in the image - the formal wear of the standing figure set against the bare chests and earth-toned fabrics of the seated men. It screams of social stratification and raises questions of what labor might have produced this tableau. Curator: Precisely. We can explore the orientalist gaze inherent in the photograph, highlighting how it potentially exoticizes and objectifies the sitters. How does the visual hierarchy reinforce colonial power dynamics, and what narratives are intentionally—or unintentionally—being conveyed? We need to acknowledge this as not simply a photograph but as a construct heavily laden with social implications. Editor: Agreed. Considering its materiality, I wonder about the context in which this print would have circulated. Was it meant for European audiences? Was it attempting to depict and preserve what was perceived as a vanishing indigenous culture, thus feeding into existing notions of progress and development? Or perhaps meant to showcase control? Curator: All are possibilities, and it's critical to unpack the assumptions and ideologies embedded within these representations, not to reduce the humanity of those depicted but to provide layers for discourse surrounding identity, representation, and the pervasive effects of colonial governance. Editor: And the act of photographic portraiture itself, even its staged nature, suggests the capture of labor, time and resources funneled to those with control over the means of image production. How were these materials acquired, processed and deployed to create a colonial record such as this? The processes and material context further cements a global political imbalance. Curator: Looking closely, the gestures and expressions on the seated figures range from guarded curiosity to veiled indifference, complicating any singular interpretation of docility. Editor: Ultimately, grappling with photographs like this forces us to confront not only the history of colonialism but also our own positionality as viewers engaging with a visual legacy fraught with ethical implications. It challenges us to examine who controls the narrative and how we can critically interpret these representations. Curator: Indeed, reflecting on this photo is like excavating layers of social tension through an intricate record. The visual details provoke more questions than answers. Editor: Exactly; that is how we give this image contemporary relevance as more than a quaint glimpse into the past but as a tool of dialogue about persistent political imbalances in the postcolonial present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.