Portret van Gaston Jean-Baptiste van Orléans, te paard after 1627

0:00

0:00

crispijnvandeiipasse

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

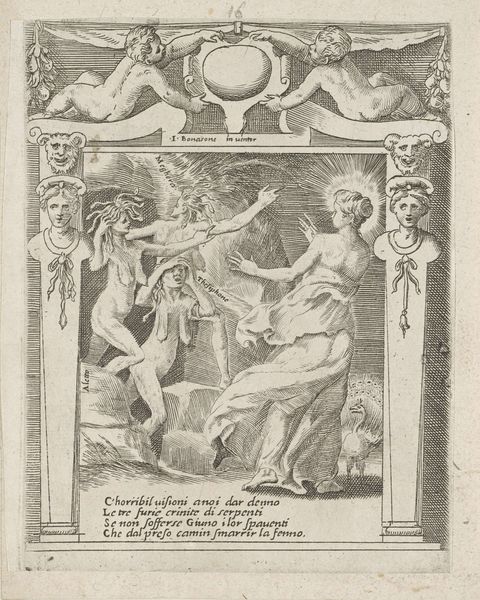

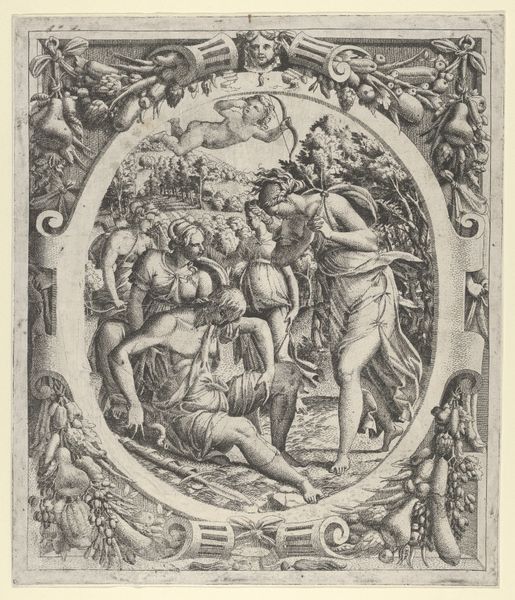

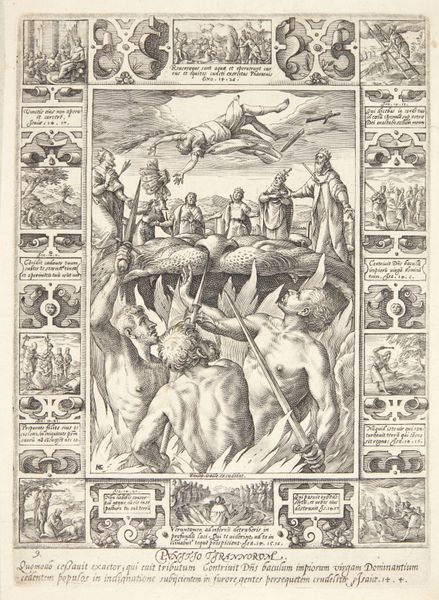

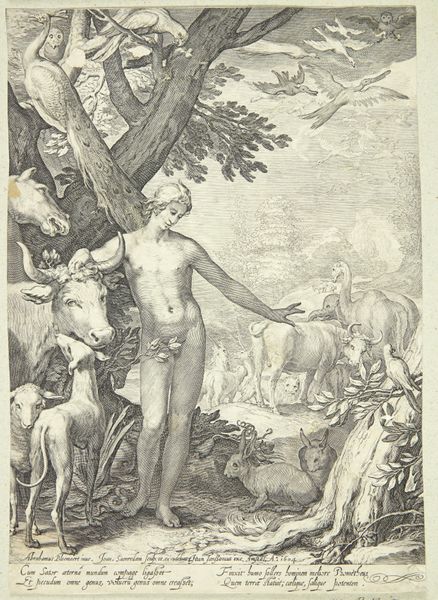

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

pen illustration

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

form

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 289 mm, width 199 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Look at this intriguing print, "Portrait of Gaston Jean-Baptiste of Orléans, on Horseback," made after 1627 by Crispijn van de Passe the Younger. It's currently housed in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My immediate impression is how meticulously detailed the rendering is. The figure feels weighty, and there’s an overall stiffness, perhaps reflecting the social constraints of the time. You can almost feel the pressure of the engraver’s hand on the copperplate. Curator: The composition is rife with symbolism, as was typical of Baroque portraiture. Gaston, the brother of King Louis XIII, is depicted heroically on horseback, but the surrounding figures are allegorical representations, aren’t they? There is an elaborate crown and coat of arms above the equestrian portrait and chained figures below, and each likely carries complex meanings related to Gaston’s power and dynastic ambitions. Editor: Precisely. Let’s not forget this is a print, so the accessibility of such imagery becomes relevant. How does the reproduction of this image through engraving serve Gaston's power? Was the aim for propaganda? To glorify nobility, legitimize power, and perhaps inspire awe or even fear? I'd wager it reached a relatively wide audience. Curator: Certainly. The allegorical figures emphasize specific attributes and virtues associated with Gaston. What’s interesting to me is how these symbols echo established tropes in European art. The influence of classical antiquity, for instance, with the female figures evocative of ancient goddesses. How the symbolic weight given through such an artistic construction can add to a subject’s legitimacy is really compelling. Editor: And the material realities, too. The labor invested, the tools, the circulation of images in 17th century society–it paints a vivid picture of that time. Look closely and you can see the dedication of the engraver, in a medium demanding a great amount of work and technique. The type of paper would matter, the ink, everything pointing towards an effort to solidify a man’s position, which becomes physically tangible through labor and artistry. Curator: I find that such prints, like this engraving by van de Passe, offer unique glimpses into cultural memory. Gaston’s aspirations, fears, and ultimately his legacy, as mediated through the symbolism of his era, speaks volumes about the period. Editor: Agreed. Studying the labor and materials enmeshed in image creation—from copperplate to paper— reveals much about social structures of 17th-century France, beyond the grand symbols and allegorical display. It highlights how the image itself is material, deeply embedded within a particular moment.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.