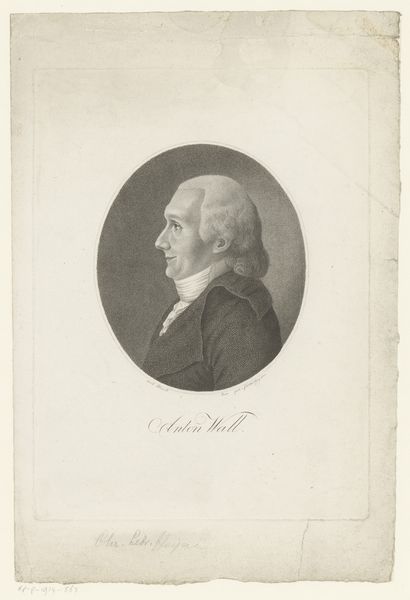

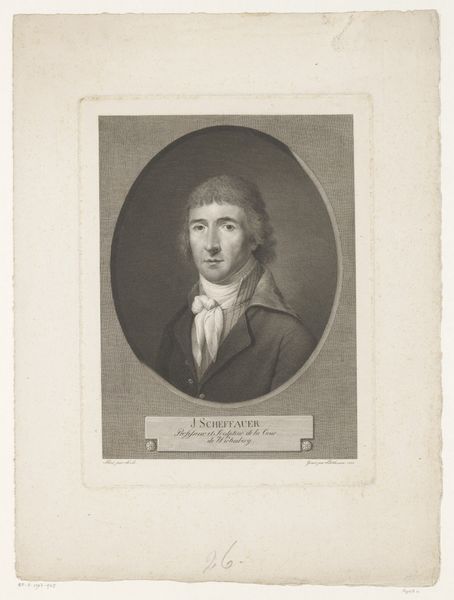

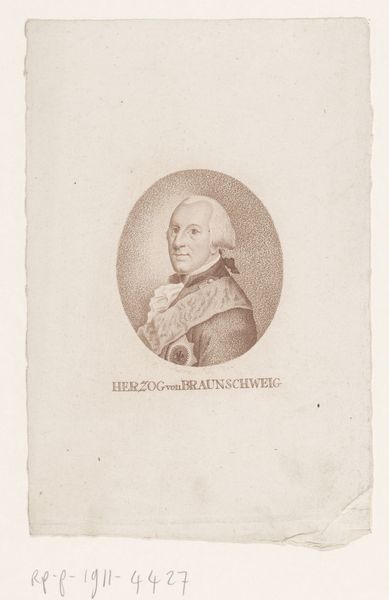

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: 166 mm (height) x 117 mm (width) (plademaal)

Curator: This is a print dating back to 1799, an engraving rendering Carl August Struensee von Carlsbach. The piece currently resides in the collection of the SMK, the National Gallery of Denmark. Editor: An immediate impression is how carefully wrought the rendering is! Considering its relatively diminutive size, the textures achieved through the engraving process convey an imposing formality. Curator: It's fascinating to consider the weight these kinds of images carried, not merely as portraits but as visual symbols of power and legacy, encoding the subject with the gravitas expected of a Prussian minister. Editor: Indeed. And the choice of engraving speaks to accessibility; prints allowed for wider distribution of imagery and ideas, a visual technology of governance and image crafting available beyond the aristocratic class. You can consider this object to participate to the expansion of civil servant culture across Europe during the late XVIII Century. Curator: Certainly. This reminds us that such portraits also perform an interesting cultural function. The crisp realism here is intriguing: his gaze meets yours head-on, as if daring the viewer to question his authority, but he seems… kind, actually. Perhaps deliberately so. It can signal probity and trust. Editor: Well, that depends on who's holding the print, I’d argue! Its meaning would shift depending on whether it hung in a Prussian bureaucrat's office or circulated in a region experiencing the burdens of Prussian administration. Think of the economic infrastructures sustaining the printing too: labor relations within the print shop, the networks for distributing the final image... Curator: Of course. What stands out, now, is the oval shape which creates the kind of "window into history," reminding us we are, in fact, engaging with a crafted representation. That framing invites interpretation and the continual construction of memory. Editor: Absolutely, and I also now reflect on how something as reproducible as an engraving is still touched by a craft of human hand and is embedded within an industry operating with limited resources within precise geopolitical conditions. Curator: Thank you for illuminating its contextual reach; now I'm keen to learn more about 18th-century printmaking! Editor: And for reminding us how even realist images work to create icons.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.