carving, metal, relief, sculpture

#

portrait

#

carving

#

baroque

#

metal

#

sculpture

#

relief

#

sculpture

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

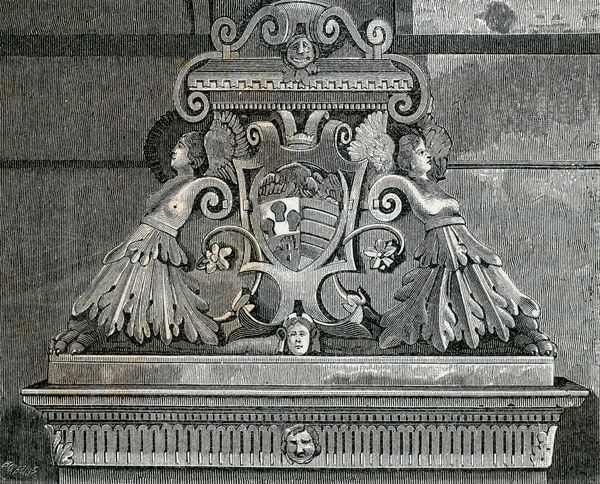

Curator: Immediately, I'm struck by how much power and status are being communicated through this dense ornamentation. Editor: Indeed. We are looking at a "Gevelsteen met het wapen van Wolpherd Hendrik Drinkveld," a relief sculpture, likely carved around 1735. Notice the way the sculptor employed both additive and subtractive methods working with the stone to create the coat-of-arms, all the ornamentation, including what looks like a heraldic boar, and of course, the inscription with the name Drinkveld. Curator: Let's think about the context, though. What does it mean for someone to have their personal heraldry displayed so prominently? Who was this Drinkveld and what claims was he making about his social and political power in commissioning such an imposing display? Was he newly ennobled, using the symbolism of the rampant boar, and the surrounding Baroque flourishes to project legitimacy and lineage? Editor: I'm fascinated by the materiality itself. What kind of stone did the artisan employ, and where did it come from? How long would carving such detail have taken? Labor was definitely being translated into power here. The means of producing an artwork like this stone panel, including how many hands were on deck and the politics involved with displaying this "door stone", would signal clear hierarchies within Dutch society. Curator: The very notion of 'anonymous' craftsmanship invites inquiry too. This wasn’t about individual artistic genius, but more likely part of a collective production system where artisans channeled their expertise into representing the ideals of their patrons, reinforcing certain social values in Dutch society. Were any women involved in producing works of heraldry like this stone panel? Where they excluded from these commissions by trade guilds? Editor: Precisely. The intentional visibility of the carving – intended to face outward toward the street – served a specific social purpose tied directly to material conditions of access and commerce within a developing economy based heavily around merchant endeavors. Consumption becomes another material; the Drinkveld’s status consumption manifested tangibly through commissioned stonework is a political claim, wouldn't you say? Curator: Absolutely. It serves to remind viewers of specific roles played within society, perhaps less obvious now as brick buildings became the norm for construction without displaying aristocratic heraldry. So while aesthetically pleasing, understanding how it functioned becomes key! Editor: Definitely a reminder of how process, skill, material, and place come together in making these historical voices come alive to the visitor.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.