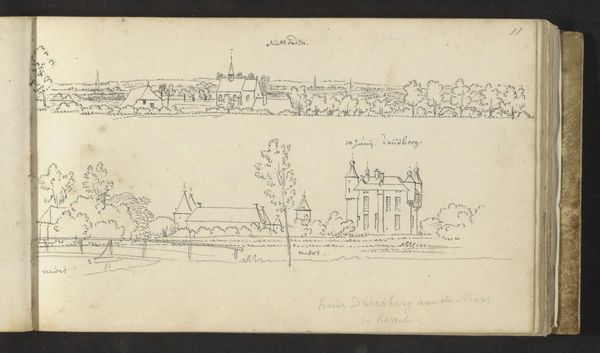

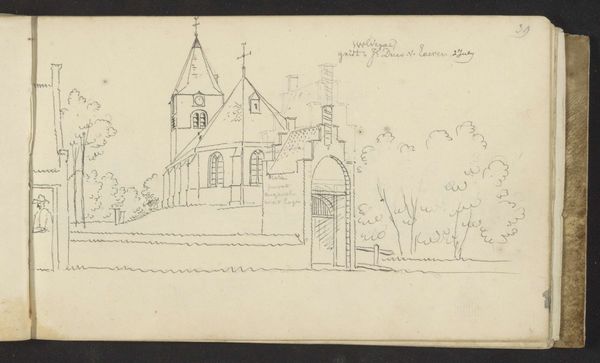

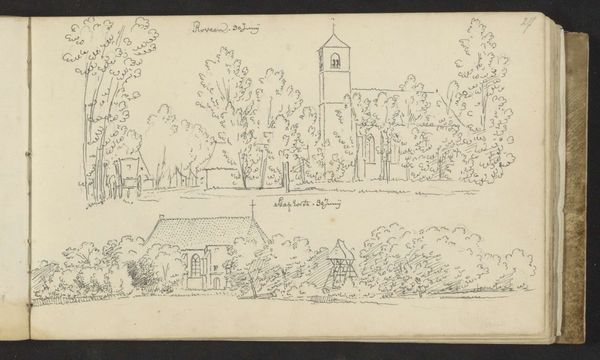

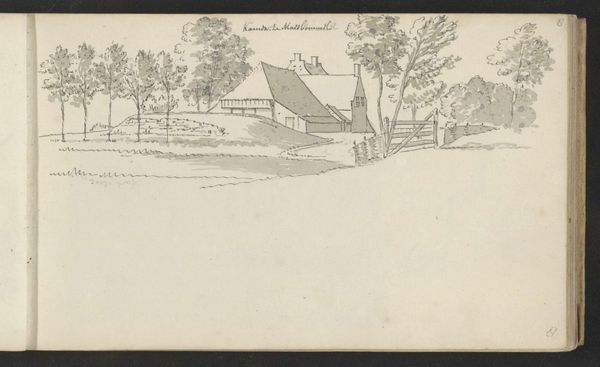

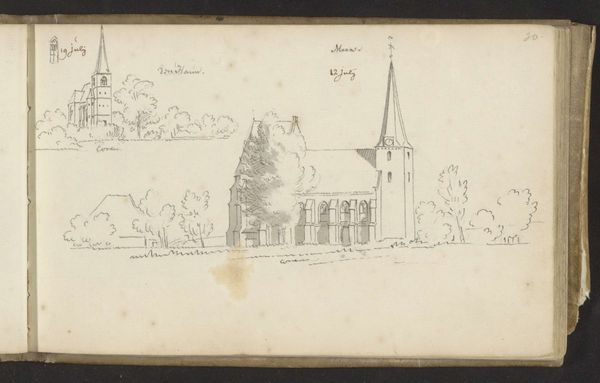

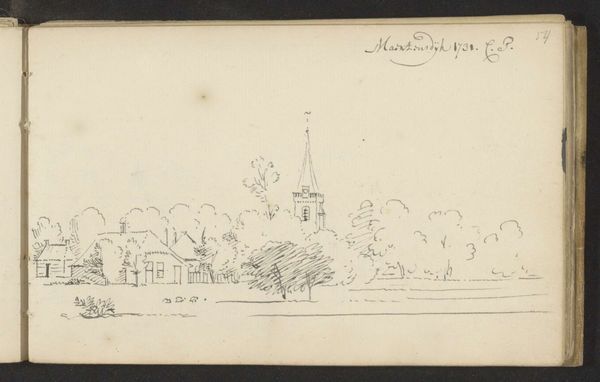

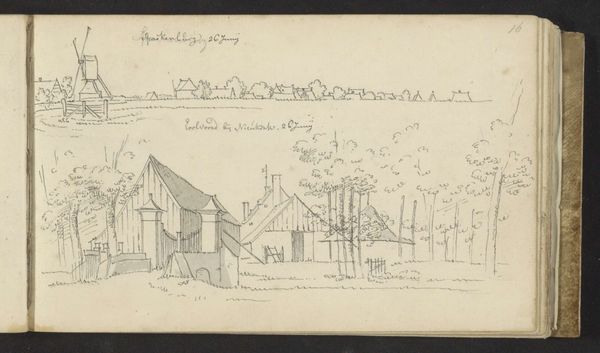

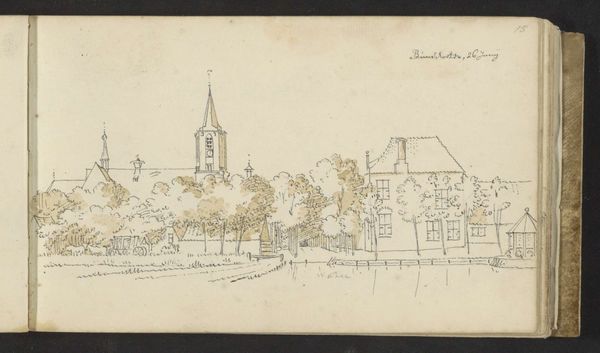

Kasteel Spreeuwenburg bij Coudewater en gezicht te Middelrode 1701 - 1759

0:00

0:00

cornelispronk

Rijksmuseum

drawing, etching, pencil, architecture

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

pen sketch

#

etching

#

landscape

#

pencil

#

architecture

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

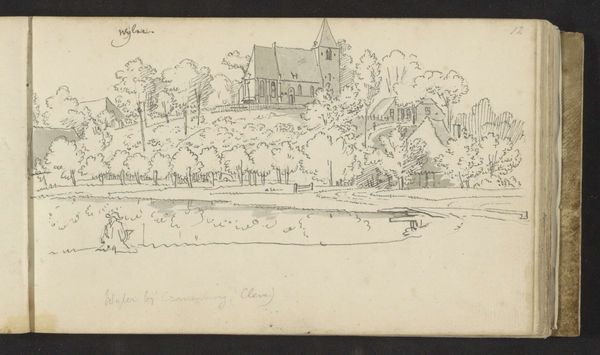

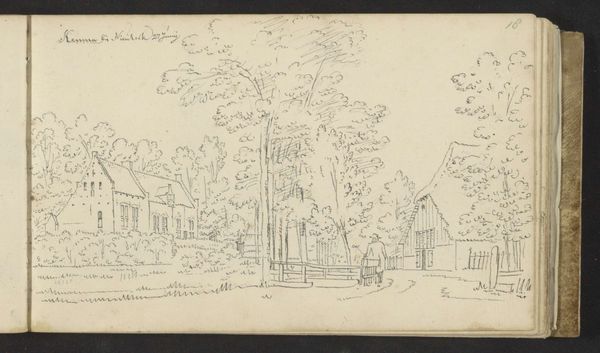

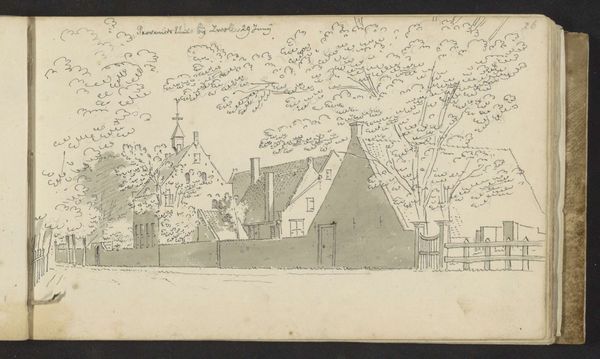

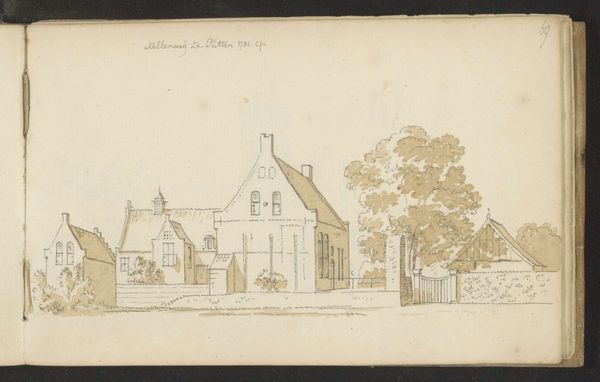

Curator: Before us is "Kasteel Spreeuwenburg bij Coudewater en gezicht te Middelrode" by Cornelis Pronk, dating roughly from 1701 to 1759. It is currently held in the Rijksmuseum. It’s an interesting study in pencil and etching. Editor: My initial reaction? Evocative. There’s a simple beauty in the linearity, the spare use of line creating volume, mass, depth... I find it remarkably effective. Curator: Yes, the technique is deceivingly simple, isn’t it? Pronk, though celebrated, operated in a commercial landscape. He was providing visual documentation for wealthy patrons who wanted records of estates and properties, their holdings and status made plain through commissioned art. Editor: That is indeed relevant: it changes how we consider the form and execution. How does that context change the importance we place on the architecture itself, or perhaps on the representation of ownership? I’m drawn to the composition of the upper register of this sketch— the contrast between the relatively strict architectural detailing of the castle and that wild organic treatment of surrounding shrubbery and plant life. The geometry versus free-form expression of it all. Curator: It does seem to reinforce that era’s perspective on the relationship between humankind and the landscape itself. Control and order over natural forces are a constant motif. Consider the materials too— pencil and etching were readily available and relatively inexpensive. These made mass production feasible, making it accessible to a growing middle class. What story does this piece tell about shifting labor practices or patterns of consumption during the Dutch Golden Age? Editor: That being the context it’s important to not simply be a product of industry— that is why even simple lines and shapes must be thoroughly evaluated. If we remove social factors from art it will not necessarily devalue our ability to dissect form, line and structure but we lose context! What is there if there is no historical reading! The geometry on display versus the natural world represents such a perfect symbology... Curator: Exactly, because even the artistic act – the very creation of that tension between geometrical lines and softer vegetation, even if a kind of record-keeping, has economic and social consequences. I like to think how the artistic touch affected material conditions during a specific historical context. Editor: I concur! It also gives a deeper resonance to such otherwise seemingly quotidian sketches! The impact resonates on all!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.