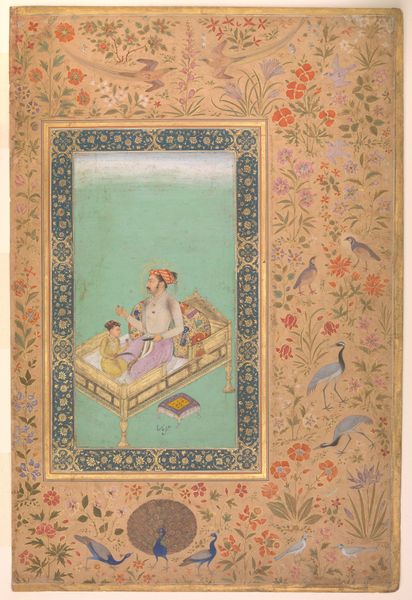

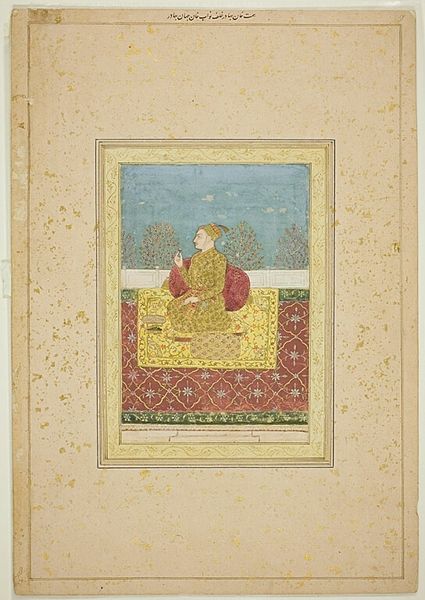

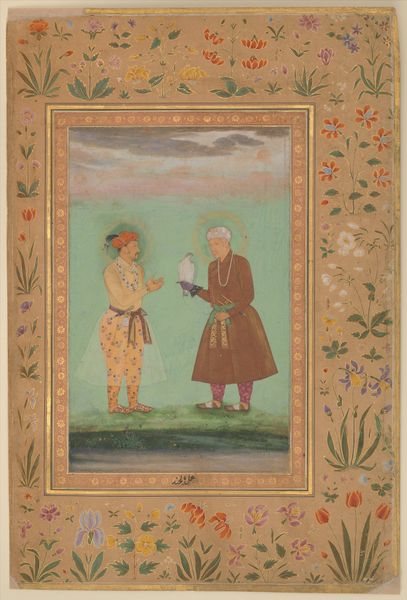

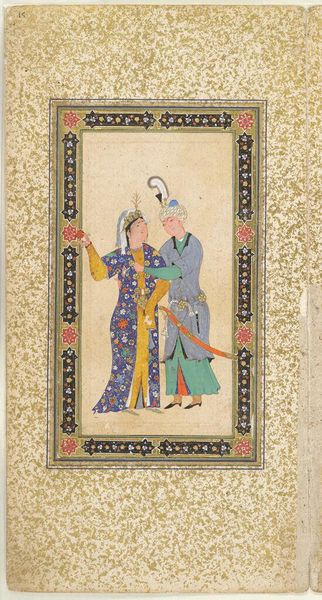

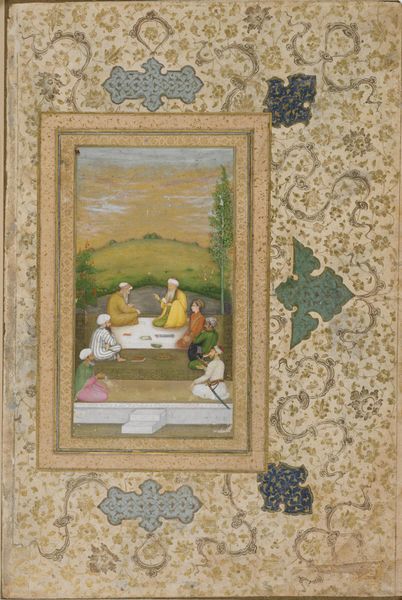

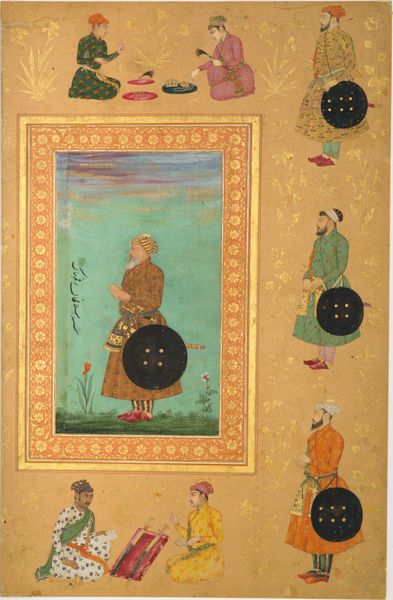

"Jahangir and His Vizier, I'timad al-Daula", Folio from the Shah Jahan Album 1505 - 1640

0:00

0:00

painting, watercolor

#

portrait

#

water colours

#

painting

#

watercolor

#

islamic-art

#

miniature

#

calligraphy

Dimensions: H. 15 3/8 in. (39 cm) W. 10 3/16 in. (25.9 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Let’s take a look at “Jahangir and His Vizier, I'timad al-Daula,” a folio from the Shah Jahan Album by Manohar, created between 1505 and 1640. It's currently held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: My first impression is one of incredible delicacy. The scale is intimate, and the use of watercolors creates a sense of softness, almost dreamlike, yet rich. Curator: The context here is critical. The painting, made with watercolor, is a fascinating example of Mughal portraiture, offering a glimpse into the courtly life of the period. What does the vizier presenting Jahangir with what appears to be a manuscript or decree suggest to you? Editor: Visually, the document is important. Both figures appear serious; the manuscript signifies knowledge, law, power—the very instruments of governance. Gold calligraphy suggests these ideas in visual form. This reinforces a world of refined aesthetics as symbols of social standing. The floral decorations almost amplify the central image, as in prayer beads surrounding a religious painting. Curator: Absolutely. Think about Jahangir's political and personal reliance on I'timad al-Daula. By situating the Vizier within such an intimate and idealized space, what’s really at play? To elevate the status and lineage through visual arts makes him more credible and believable. How might the court at the time received the artwork and responded? Editor: Considering its visual language, viewers in that context would’ve easily interpreted the visual vocabulary. The halo, canopy, and ornate dress instantly code this figure to a kingly power. By association, then, the Vizier himself must have held important, powerful position in the royal hierarchy. Curator: The interplay of these coded figures suggests gendered power. In courtly settings like the Ottoman, being adjacent to powerful people, especially kings or shahs, became gendered territory. To become vizier at the time was about climbing that same gendered and exclusive access. Editor: I see this portrait not just as a record, but also as a carefully crafted assertion of authority, communicated through specific iconographic cues and aesthetic choices, to impress the value in the mind of a viewer then. Curator: And situating this artwork in our moment prompts us to reconsider whose narratives and subjectivities were made most visible, whose weren’t, and why these questions of representation continue to be so vital today. Editor: A powerful visual summary for enduring notions of power and politics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.