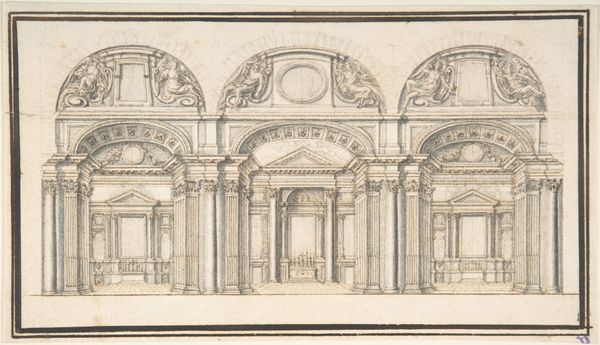

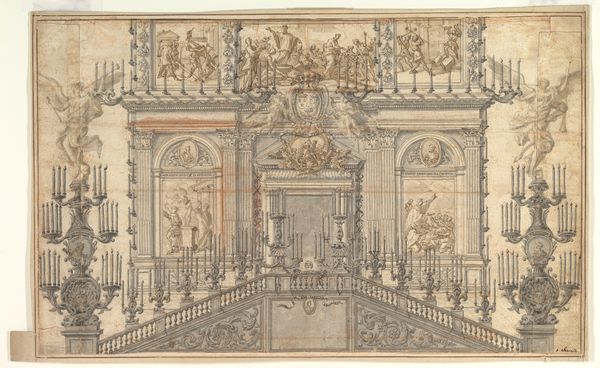

Design for an Architectural Interior 1760 - 1810

0:00

0:00

drawing, tempera, print, ink, architecture

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

tempera

# print

#

ink

#

architecture

Dimensions: 6 7/16 x 11 11/16 in. (16.3 x 29.7 cm.)

Copyright: Public Domain

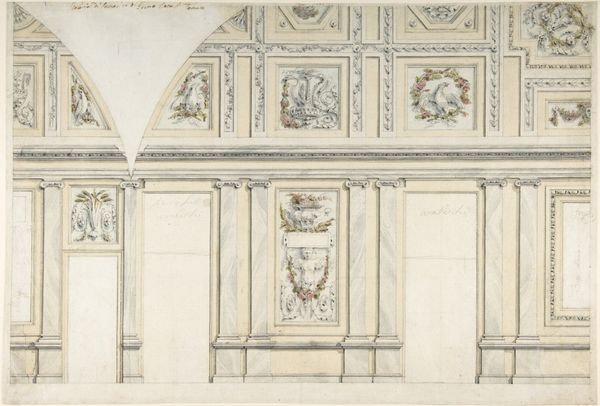

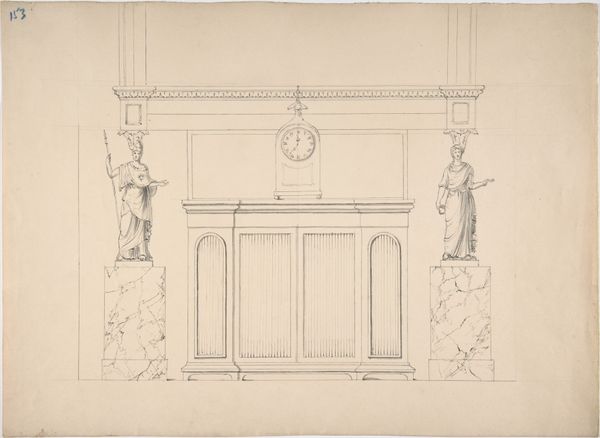

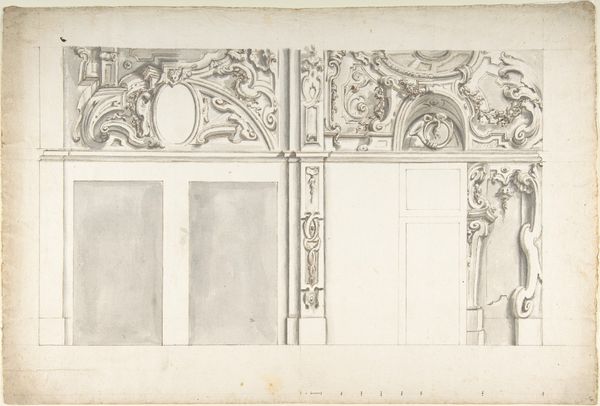

Curator: Here we have "Design for an Architectural Interior," created between 1760 and 1810 and now residing at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The artist, Pierre Nicolas Ransonnette, used ink, tempera, and print to compose this piece. What are your first thoughts? Editor: It feels surprisingly serene for such a formal setting. There’s an almost dreamlike quality to the washes of color and the way the light filters in through those grand windows. Curator: Yes, Ransonnette beautifully captured the Neoclassical style’s aspirations. These designs weren’t merely about aesthetics, but projecting power and civic virtue through architectural design during a time of immense political and social change in Europe. Editor: The details, those symbolic panels depicting classical scenes, and the decorative garlands—they all speak of a desire to connect with an idealized past, almost like imbuing the space with the wisdom and authority of the ancients. Curator: Precisely. The architecture itself is designed as a didactic tool, reinforcing social hierarchies and the established order. Consider how these spaces would function—ceremonial gatherings, elite displays of patronage… it's all carefully orchestrated. Editor: I do wonder about the figures in those panels. They're rendered quite subtly, almost like ghostly presences watching over the room. It introduces a feeling of… history weighing down on the present? Or perhaps celebrating it. It’s ambiguous, but suggestive. Curator: That's a fascinating point. One could argue they serve both purposes. By invoking these historical narratives, the architecture seeks legitimacy, while also reminding its inhabitants of the standards expected of them. This was an era obsessed with moralizing through visual imagery. Editor: Seeing this makes me think about how architecture embodies the aspirations and anxieties of its time. In some ways, buildings can become massive, permanent symbols of our values, which can then affect public space and individual emotion. Curator: Yes, and Ransonnette's drawing, by capturing the nuances of this idealized interior, prompts us to consider the complex relationship between art, architecture, and social order in the 18th century. It definitely underscores how these meticulously crafted spaces sought to mold not just bodies but also minds. Editor: After looking at this design, I realize the potency of imagery as social instruction and of architectural representation, I really am grateful for this glimpse into history through its forms and signs.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.