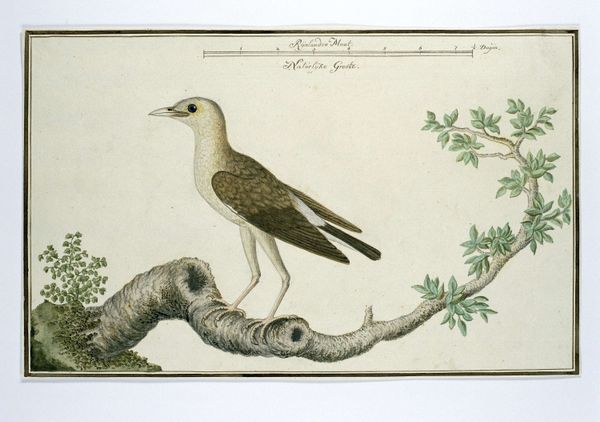

drawing, watercolor

#

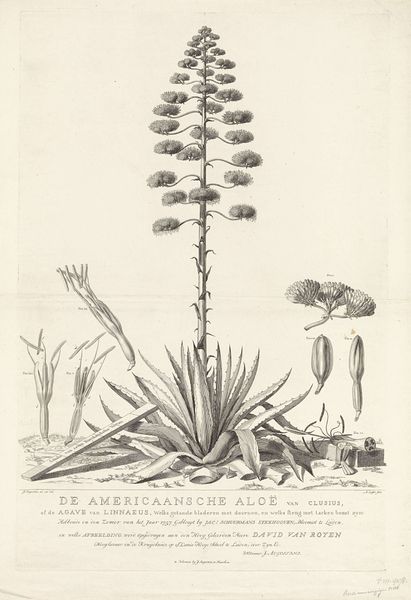

drawing

#

water colours

#

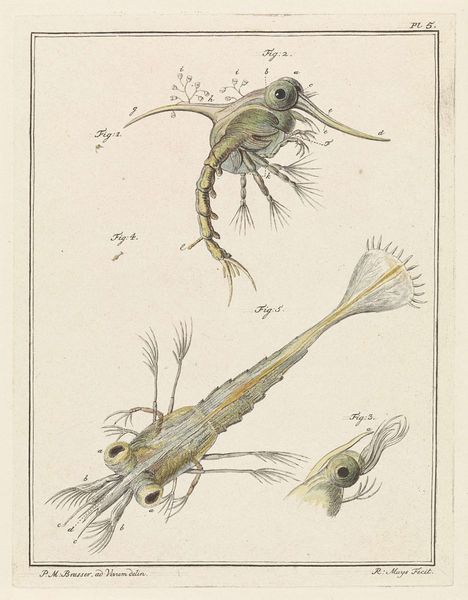

ink painting

#

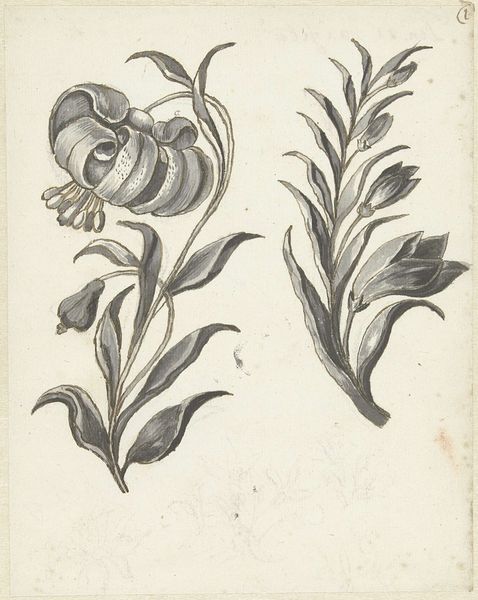

landscape

#

watercolor

#

watercolor

#

realism

Dimensions: height 660 mm, width 480 mm, height 369 mm, width 239 mm, height mm, width mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

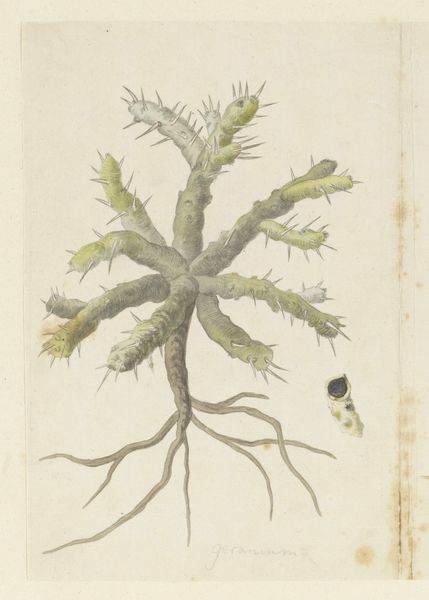

Curator: There’s a certain vulnerability to this drawing. It’s called Apiacea or Umbelifera and is thought to have been made sometime between 1777 and 1786. The artist was Robert Jacob Gordon, who captured it in ink and watercolour. Something about the pale colours and careful detail suggests a delicate, almost melancholy mood to me. What’s your first take? Editor: I see fragility too, but more in terms of coloniality. It's difficult to overlook the act of cataloguing nature by Europeans during that period. The plant and the bird, carefully rendered—are they subjects being stripped of their context, turned into specimens? This wasn't objective science. It served power. Curator: Absolutely, and it’s an important point. I suppose, on one level, it's a study of this plant and a small bird, placed rather perfectly on a bare branch – and how amazing that is; this small creature sitting calmly within what becomes both a scientific and an artistic document! I find this plant quite sculptural, this kind of root ball jutting forward – a living, branching form rendered in muted tones. The detail in those seed heads…it's almost devotional. Editor: That devotion has a flip side. The bird perched so obediently reminds me of the ways in which the colonial gaze often idealized or romanticized the landscapes they invaded, obscuring the realities of exploitation and erasure of Indigenous knowledge systems. Even what feels objective about the approach serves colonial domination. Curator: I suppose it's about seeing beyond the immediate beauty, the technique, the craft, isn’t it? Understanding the historical weight… and that opens it all up to a much broader conversation about who gets to represent nature, and for what purpose. It really does bring into question the idea of objective beauty itself. Editor: Precisely. The very act of naming, of classifying… It all has political consequences. Even this quiet watercolor can become a site of resistance if we allow it to challenge the authority behind the colonial vision of nature. Curator: It’s amazing how a simple drawing of a plant and bird can hold so much, reflect so much back at us about our own relationship with history, with nature and each other. It shows the quiet radicality that art can provide, prompting conversation between aesthetics, representation, and power. Editor: Yes, what appears merely descriptive serves also to justify power relations. By dissecting the gaze that created it, this quiet botanical study can start louder, much needed, dialogues.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.