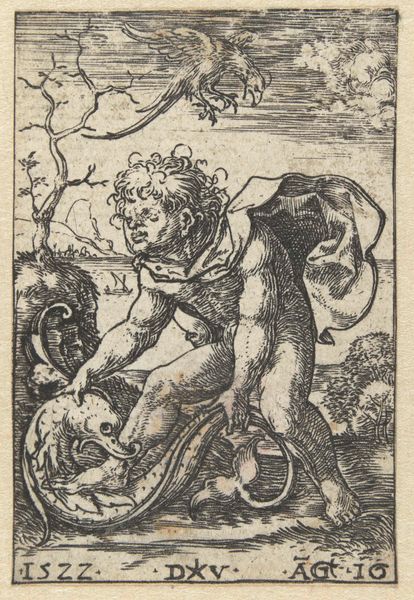

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

# print

#

figuration

#

coloured pencil

#

pen-ink sketch

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet: 1 13/16 x 3 3/16 in. (4.6 x 8.1 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Sebald Beham's "The Little Buffoon," an engraving from 1542, immediately strikes me with its intricate detail and the almost comical pomposity of its central figure. The burly toddler seems both vulnerable and absurdly self-important. Editor: It’s a peculiar mix, isn't it? My initial reaction is that there is a satire on full display; the chubby figure juxtaposed against those swirling calligraphic banners reads as an intentional jab at authority. It speaks volumes about social structures of the time, questioning power dynamics. Curator: Let’s examine how Beham directs the gaze. The figure, although small, dominates the composition, thanks to the tightly woven banners that seem to almost prop him up. His direct gaze meets ours, holding us captive within this bizarre scene. His rotundity—almost exaggerated—provides an interesting tension. And the impish smirk, it pulls the whole scene into absurdity. The materiality of the engraving allows for the sharpness of line, reinforcing detail, lending the entire figure this monumental presence despite its small stature. Editor: Indeed, but consider who is afforded monumentality, and what cultural statements that artist makes by centering this figure. We can delve deeper when we contextualize within Northern Renaissance sensibilities of hierarchy and class. The engraving medium itself made it accessible; thus, was it mocking someone above him? A satire such as this could function as a form of subversive social commentary—particularly within rigid 16th-century social hierarchies. Curator: But consider the purely visual aspect: the rhythm of the lines! Note how they contour the forms of the figure and objects to create contrast through shifts in the marks used by the artist, modulating weight and the optical grey values achieved. Also, those meticulously rendered banners— they aren’t just support structures for the text but active design elements, lending a sense of motion. Beham’s technique is remarkable when viewed solely from that perspective. Editor: Absolutely. What seems decorative in those winding bands is a form of political language—perhaps even coded. We need to decode that in relation to the era; perhaps it is speaking against religious dogma. The little buffoon becomes an antihero or subversive figure. These engravings became powerful and portable ways to speak to, and critique the people in power. Curator: I still see an emphasis on compositional balance and tension – on its form more than solely symbolic gestures. I value its presence within a complex art historical continuum, referencing and engaging within a longer discussion about drawing, mark making and its place amongst its contemporaries and artists that came after. Editor: I'm more convinced than ever of the social impact of artworks. In fact, the figure's very presence, particularly during that time, suggests the powerful confluence of art and social activism. It's an exceptional case study.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.