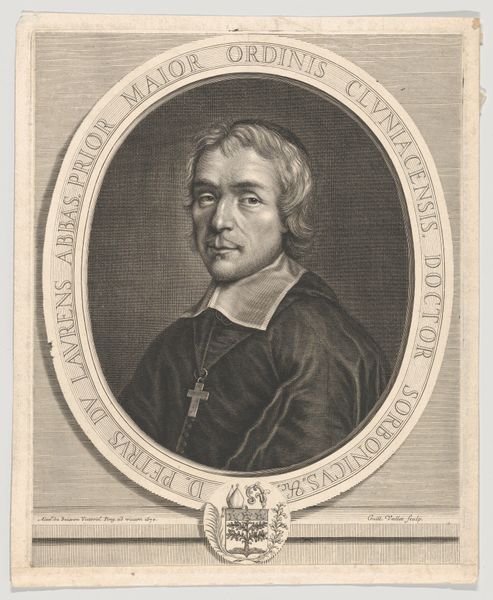

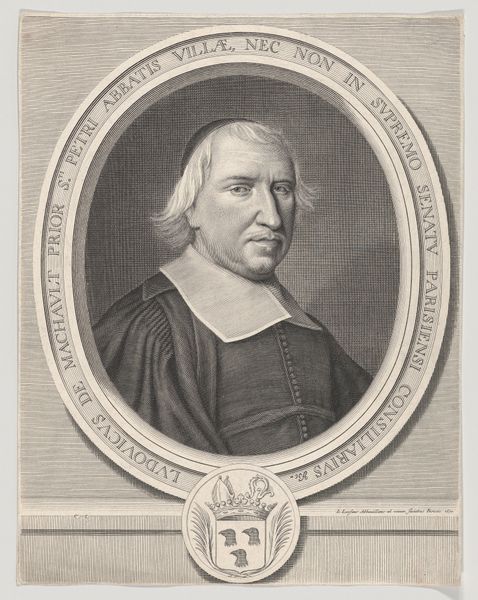

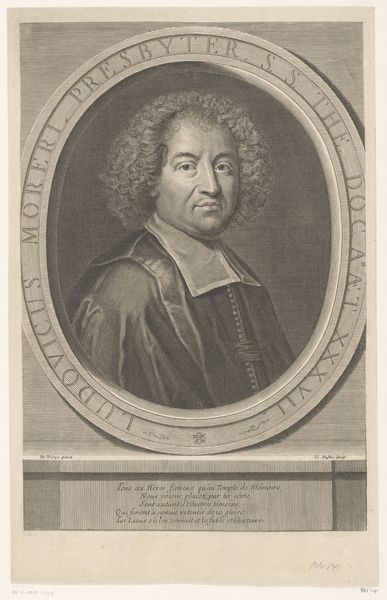

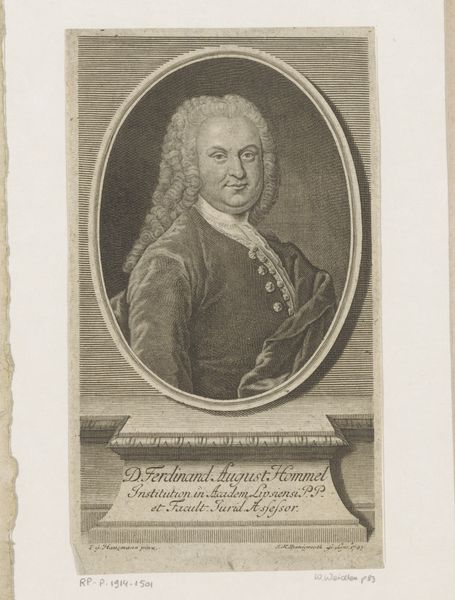

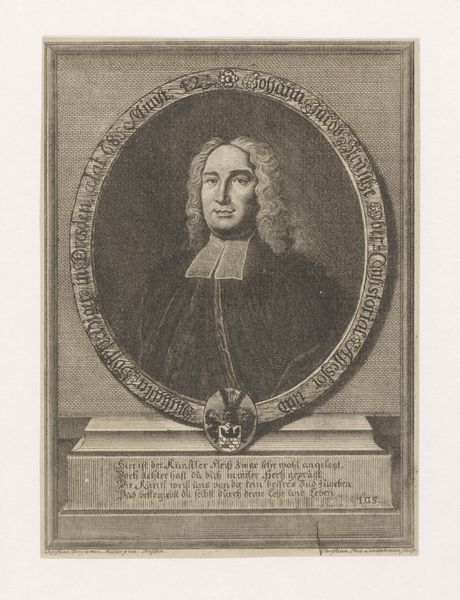

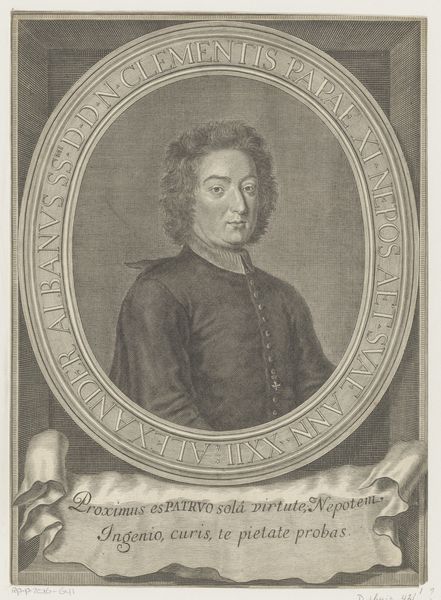

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

baroque

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

charcoal drawing

#

pencil drawing

#

portrait drawing

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 228 mm, width 200 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: At first glance, the gentleman in this 1745 engraving exudes a certain sternness, doesn't he? There's a gravitas to his gaze that speaks volumes even before we delve into the context of the piece. Editor: Absolutely. The weight of expectation seems to settle heavily on his shoulders, almost palpable despite the delicate lines of the engraving. Let's contextualize this. We're looking at Francesco Polanzani's "Portret van Camillo Tacchetti," currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Curator: Yes, and as the inscription circling the oval frame denotes, this is Camillo Tacchetti Veronese, Abbot of the Lateran Congregation, portrayed in his 42nd year. Now, the symbols of his office are understated, aren't they? He is pictured, yet, we, the audience of a later time, see in his posture a symbol of dignity. Editor: Precisely. The Baroque era often intertwined personal portraiture with expressions of societal standing. Note how the engraving itself – the *print* – becomes part of the message, signaling accessible (if relatively exclusive) public imagery. This Abbot, in having this image reproduced and disseminated, plays an active part in creating the desired perception of his public image. Curator: Indeed, and what is so compelling, speaking about perception, is the very human aspect brought to life by the hand-drawn character of the medium itself. The lines create a texture that humanizes him. See, how in contrast to an actual painting with vivid color the light here symbolizes more than what the print may appear. It is bringing his humanity forth in his day as well as to ours. Editor: And one wonders how widely these prints circulated and what purpose they ultimately served. Were they commemorative keepsakes, circulated amongst members of his congregation, or broader attempts at cementing his legacy? This is part of the enduring question regarding the role of image production within social hierarchies. Curator: In that sense, one can consider this artifact more than just an engraving; it’s an index of cultural aspiration, reproduced and circulated, an echo rippling through history. Editor: It seems to tell a silent story of a man consciously shaping his image within a world of religious and societal structures. A quiet and evocative experience of image and identity!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.