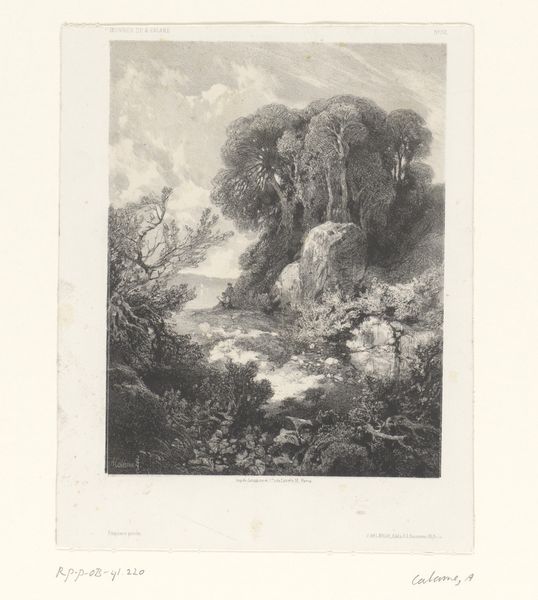

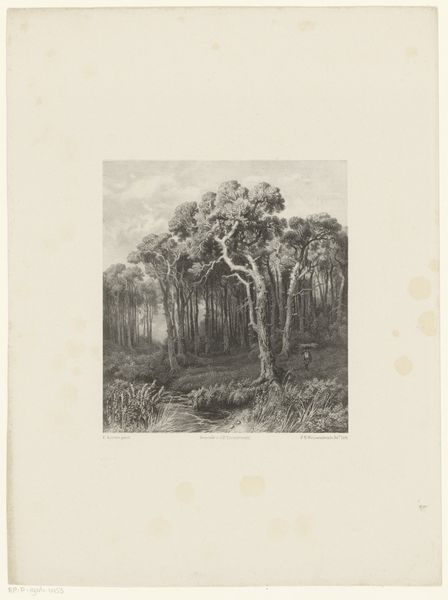

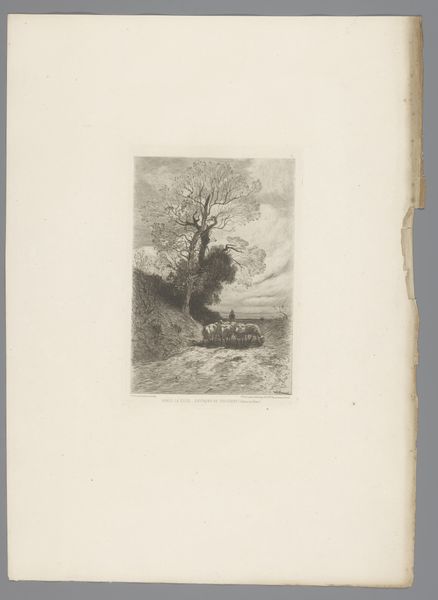

Dimensions: height 317 mm, width 245 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is "Graf van Napoleon in Sint Helena," or "Tomb of Napoleon in Saint Helena," an etching made between 1842 and 1887 by Carel Christiaan Antony Last, here on display at the Rijksmuseum. It's a piece that really speaks to the Romantic obsession with history and mortality, rendered in a medium that allows for intricate detail and broad distribution. What's your take, Editor? Editor: Oh, melancholy in monochrome! The light feels utterly desolate, doesn't it? All those weeping willow branches draped over what I presume is the tomb. It gives me the shivers, like a stage set for a particularly mournful soliloquy. Curator: Absolutely, the etching technique lends itself beautifully to the creation of that atmosphere. Note the lines; the etching process involves using acid to bite into the metal plate, allowing for deep, expressive marks. The availability and affordability of prints like these meant that romantic visions of Napoleon's exile and death could circulate widely, influencing public sentiment. Editor: It's remarkable how such a contained image—relatively small, I imagine—can conjure such expansive feelings of loss and isolation. And the weeping willow is almost cliche but works perfectly! Did everyone at the time have a graveyard stocked with them, waiting for moments like this? Curator: Well, the choice of the weeping willow is quite deliberate. It's a symbol of mourning, deeply ingrained in European culture. Beyond the obvious symbolism, the commercial aspect can't be ignored: the artist, by creating multiples, entered into a system of production and distribution, hoping to capture a share of the market for historical imagery. Editor: Of course. Still, to make something this evocative through a commercially viable medium is an art in itself. I can almost feel the dampness of Saint Helena just looking at it! It has a real immediacy; it whispers tales of thwarted ambition and island solitude. So, was there widespread market interest at the time, do we know? Curator: Historical records suggest so. The image taps into a potent mix of national pride, sorrow, and perhaps even a hint of rebellious admiration for Napoleon, so effectively transforming grief into something commodifiable. The printing of images became intertwined with national sentiment, political views and financial benefits. Editor: Well, considering the afterlife of Napoleon is still pretty profitable, the success of this image makes perfect sense! Though stripped of empire, and even life, Napoleon remains a fascinating protagonist. The composition pulls you in and traps you in the gloom of the location; the effect really lingers with you, which explains its success, I guess. Curator: It certainly does invite contemplation. It gives food for thought how mass-produced objects play such a vital part in the construction of national identity. Editor: Precisely, Carel Christiaan Antony Last’s artistic interpretation is an interesting one to remember. And it does give an afterglow that makes us think about the relationship between memory and material culture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.