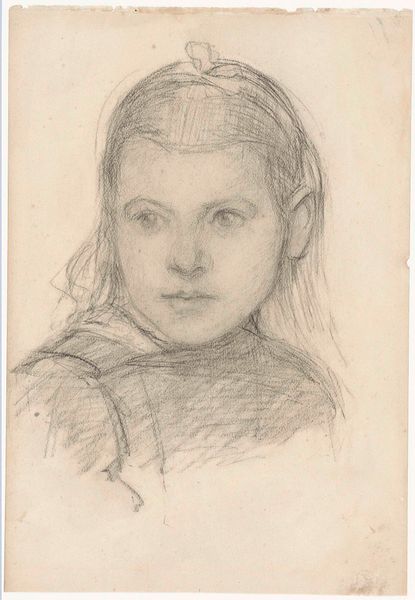

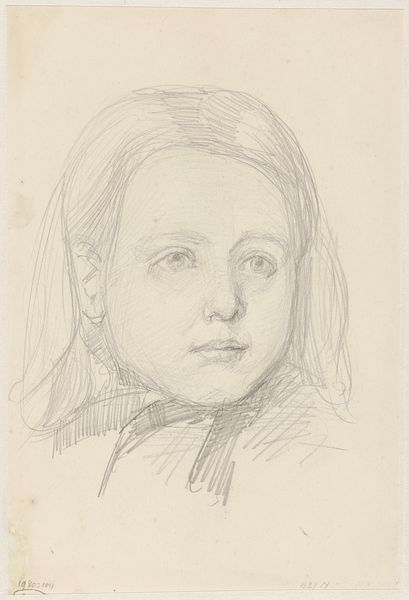

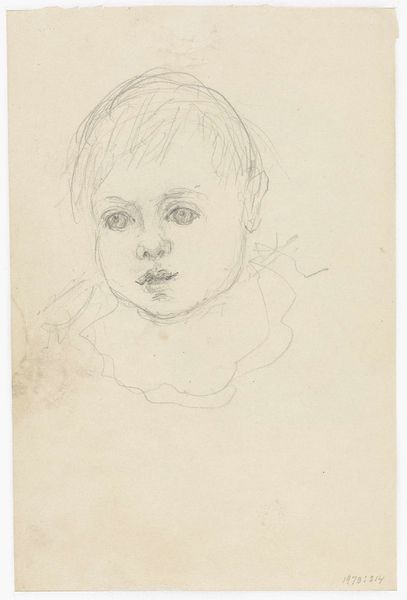

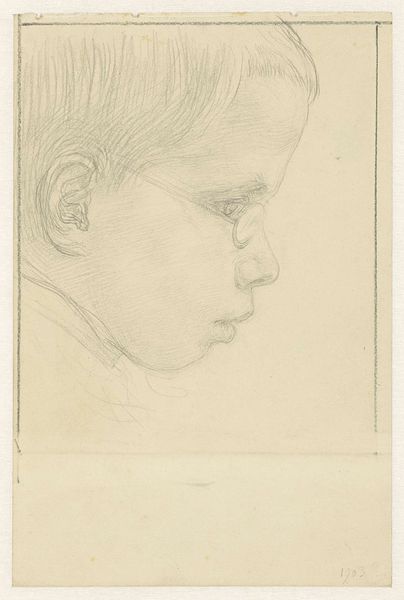

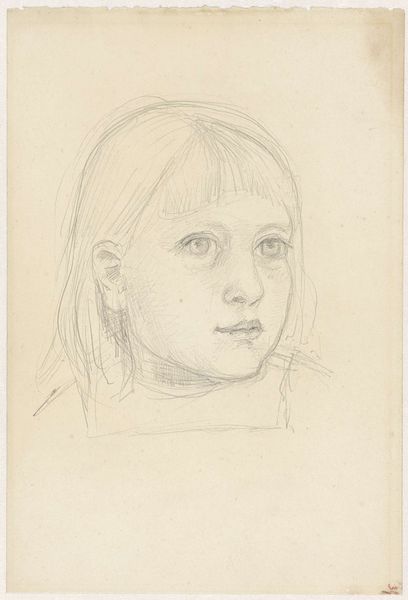

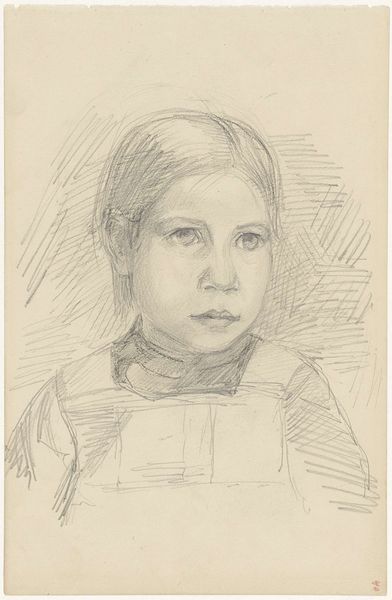

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

northern-renaissance

#

realism

Dimensions: height 309 mm, width 208 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this pencil drawing, what catches your eye first? Editor: Well, there’s a stark immediacy to it, wouldn't you agree? Almost vulnerable. I find myself immediately drawn to the child's thoughtful expression, which seems at odds with the simplicity of the drawing's execution. Curator: Indeed. What we have here is "Head of a Child" by Jozef Israëls, an artist associated with Dutch realism from 1834 to 1911, now residing here at the Rijksmuseum. I'm interested in how Israëls uses the humble pencil, typically relegated to studies, as the primary medium. What does that say about the role of drawing in 19th-century Dutch art? Editor: The medium is significant, certainly. Israëls’ choice reflects a shift away from grand academic painting toward a more direct and democratic form of image-making. Pencil allows for the creation of an intimate, affordable artwork, challenging traditional notions of high art's inaccessibility. Its reproducibility makes the image circulate widely, reinforcing prevailing social ideals, while questioning how accessibility influences artistic value and viewership, right? Curator: Absolutely, but it's more than mere reproduction. There's a rawness to the cross-hatching, an almost desperate quality in how he renders the shadows, and the child's simple clothes. Israëls doesn't romanticize poverty; he presents the reality of children working in factories or farms. Does that influence the way art depicts children in that era? How does the art market impact it? Editor: Well, the image isn’t explicitly about labor. Yet you are correct, the child's demeanor speaks to an understanding that belies his youth. And there is the problem, it shapes public sentiment about children of that period in general. It also reminds me that the institutional support of galleries and museums allows these more sober and, frankly, sad portrayals of poverty to reach a wider public, sparking dialogues around societal change and class disparity, or not. Curator: Yes, and returning to materiality, consider how the texture of the paper itself contributes to the overall effect. You can almost feel the grain beneath the pencil marks. How does the accessibility of art spaces change access to those same materials for production, and who gets left out in those production cycles? Editor: So, it becomes a cyclical question of viewership and accessibility—museums display Israëls, Israëls captures children shaped by certain social realities, impacting social perception. It also forces us to reconsider the accessibility of creative spaces, a poignant echo from our time. Curator: A powerful thought. Thank you. Editor: And to you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.