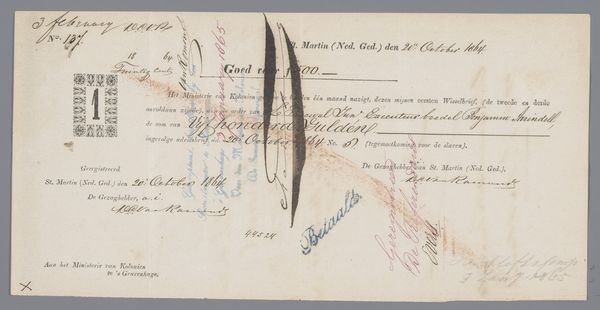

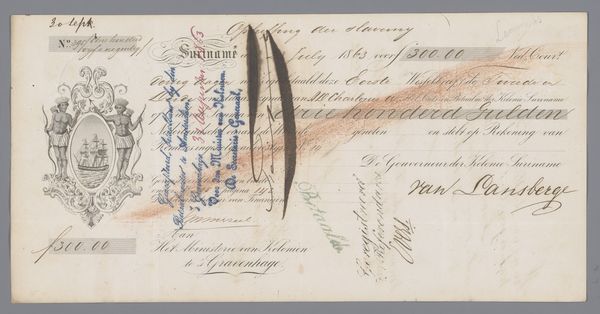

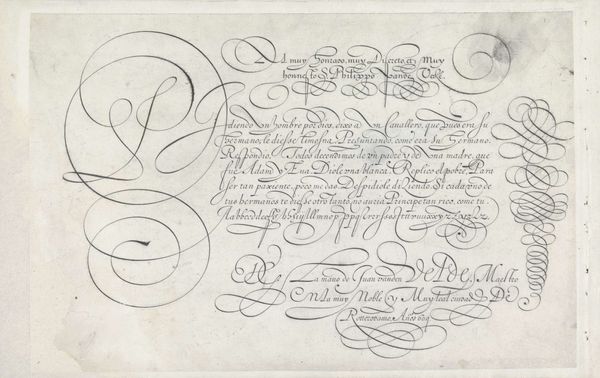

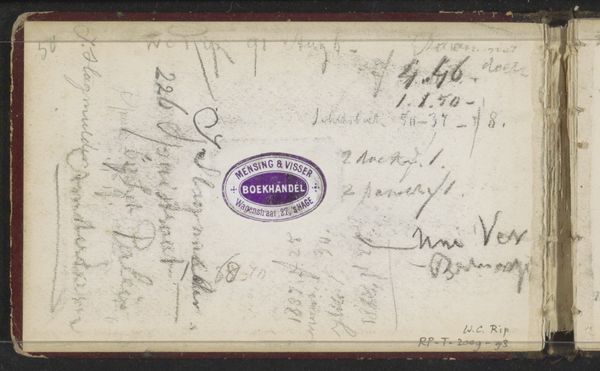

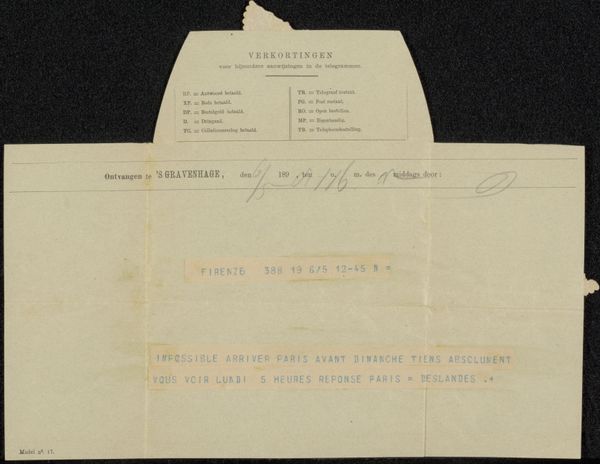

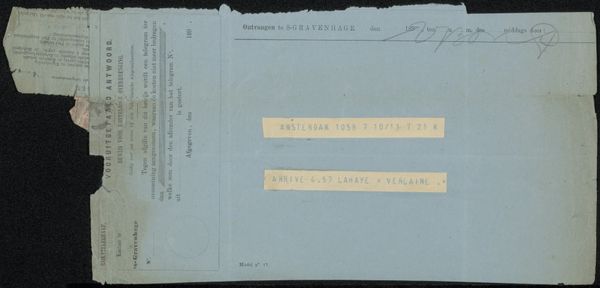

Wisselbrief voor slavenhouders in verband met schadeloosstelling afschaffing slavernij 1863 Possibly 1865 - 1869

0:00

0:00

ministerievankolonien

Rijksmuseum

drawing, collage, print, textile, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

collage

# print

#

appropriation

#

textile

#

paper

#

ink

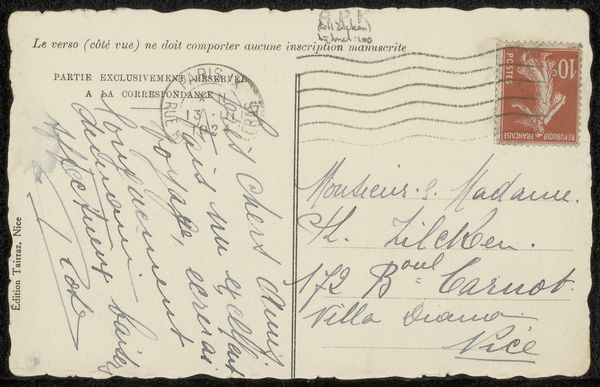

Dimensions: height 132 mm, width 266 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

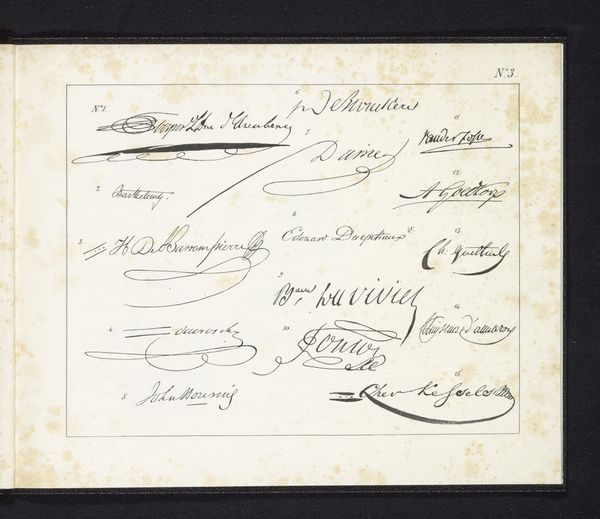

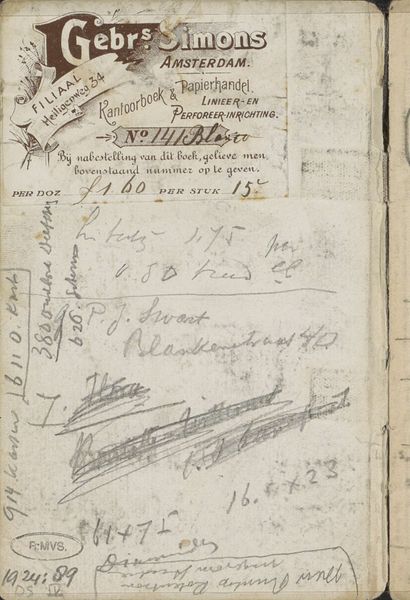

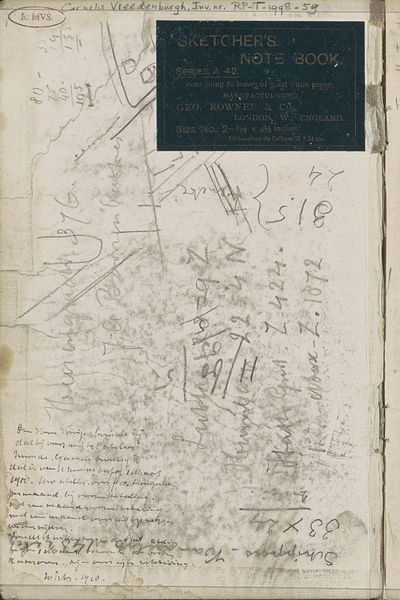

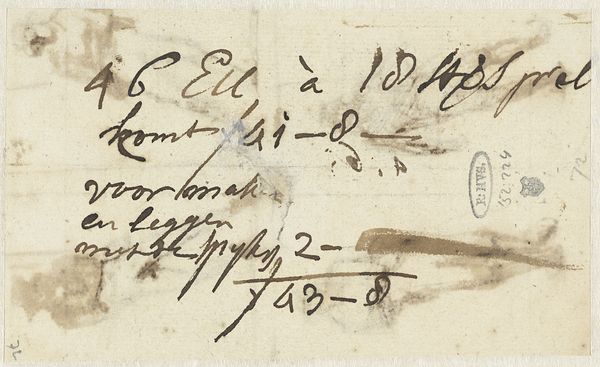

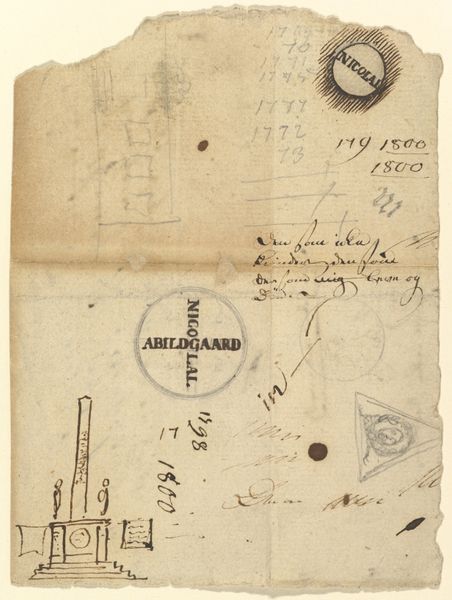

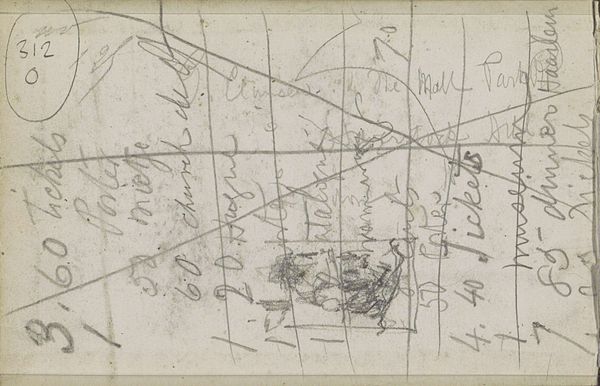

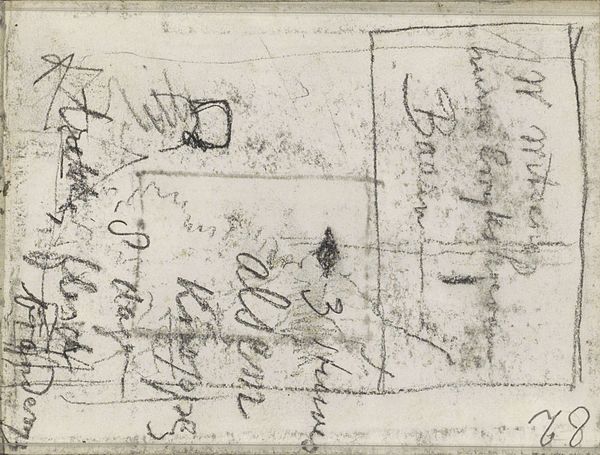

Curator: Right, let’s turn our attention to this document; it’s titled "Wisselbrief voor slavenhouders in verband met schadeloosstelling afschaffing slavernij 1863." The Rijksmuseum dates it somewhere between 1865 and 1869. It seems to be a drawing or perhaps even a collage and involves a print, textile and paper. Editor: It looks like a relic of a deeply troubling paradox. A fragile piece of paper, beautiful in its own way with the ornate script and border, belying the brutal economics at its heart. Curator: Exactly. What we're looking at is essentially a bill of exchange. These were issued to slaveholders in Suriname as compensation after the abolition of slavery in 1863. Think about that – people being given monetary compensation for releasing people from ownership. Editor: And that phrase, “bill of exchange,” it sanitizes the commodification of human beings, doesn't it? This document materializes that cold transaction; labor power rendered into ink on paper. The means of production—paper, ink, the printing press—are all implicated in this story of exploitation and then “redress” for only one party. Curator: Indeed. The elegant calligraphy feels like a calculated distraction. There's an elaborate coat of arms there featuring indigenous figures flanking a European ship. It all points to power and exploitation dressed up in finery. It is not that different from covering your crimes with a beautiful textile. Editor: And consider the journey of this paper: likely produced in Europe, shipped to Suriname, circulated amongst the colonial administration, and now preserved in a museum. Each stage representing a transfer of value, the physical artifact marking a continuous chain of capital flowing on the blood and sweat of enslaved people. Curator: Thinking about the materiality also brings to mind the hands involved in its creation, transfer and now exhibition – those who drafted it, signed it, filed it away and now preserve and present it to us. A physical web, entwined around the financial exploitation that funded them all. It's almost chilling. Editor: A document born of injustice preserved in a museum—the very act of preservation raises ethical questions. How do we reckon with such artifacts that bear witness to this legacy of brutality and attempt some accounting, even in words? Curator: It leaves you wondering about our roles today, doesn’t it? If and how, we are also implicated, woven into similar systems. Editor: Indeed, art compels us to scrutinize those links, right down to the very materials we are using in our own lives and their role in systems of inequity and privilege.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.