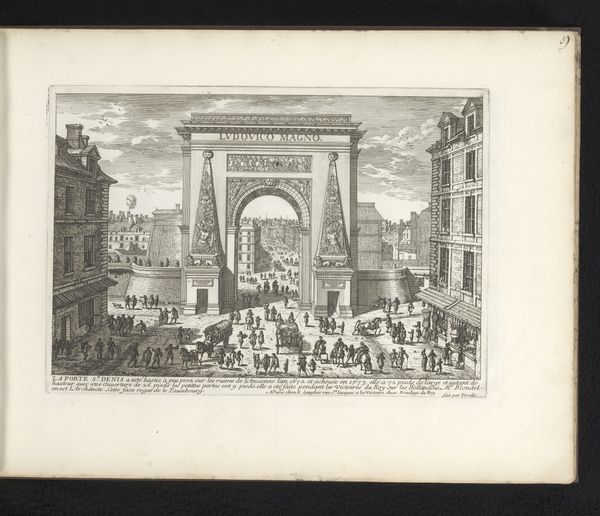

print, engraving, architecture

#

baroque

# print

#

line

#

cityscape

#

engraving

#

architecture

#

realism

Dimensions: height 201 mm, width 293 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here at the Rijksmuseum, we have "Gezicht op de Porte Saint-Martin," an engraving created by Adam Perelle sometime between 1673 and 1695. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: The intricacy of the lines is impressive. It really captures the bustling activity of this cityscape, doesn't it? There's a sense of deliberate order. Curator: Absolutely. The print exemplifies the Baroque interest in civic grandeur, depicting the Porte Saint-Martin as a symbol of royal power and urban sophistication. This wasn't just about architectural documentation; it was about projecting an image of Louis XIV's glorious reign. Editor: It makes me think about the labor involved in creating these images. Engraving is a highly skilled and time-intensive process. Each line meticulously carved to create an illusion, each one reflective of the social conditions and urban fabric depicted here. And considering that the material itself, the engraving plate, could have been repurposed multiple times. Curator: Indeed. Prints like these served a crucial public role. They disseminated visual information, influencing perceptions of Paris and the monarchy across a wider audience. How Parisians, and others throughout Europe, encountered the city would've been through images like this. It shaped public opinion and contributed to the construction of Louis XIV's legacy. Editor: The figures, rendered in such fine detail, show this convergence between architecture and everyday life. Think of the material conditions shaping these anonymous folks gathered around the gate. It all feels intertwined – the monument's creation, Perelle's work and technique, and the viewers who engaged with this print. Curator: And don't forget the patronage system that sustained artists like Perelle. Royal commissions were key to legitimizing both the artist and the monarchy itself. The production and consumption of art were deeply enmeshed in political power structures. Editor: Thinking about the economics, then, allows me to consider questions around what these prints were made of – copper and paper - and how the economics played a role. I agree that they served a broader public function. Curator: Examining this print, one sees not only a snapshot of 17th-century Paris, but also the careful construction of an image, imbued with political purpose and designed to shape perception. Editor: Precisely. By tracing these lines, one can grasp the broader material reality. This city scene serves as more than a record.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.