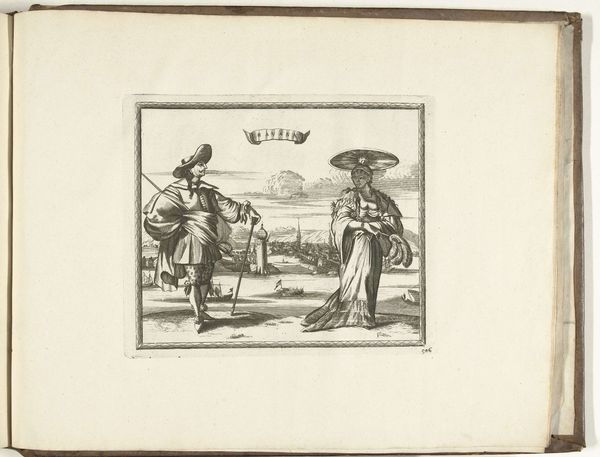

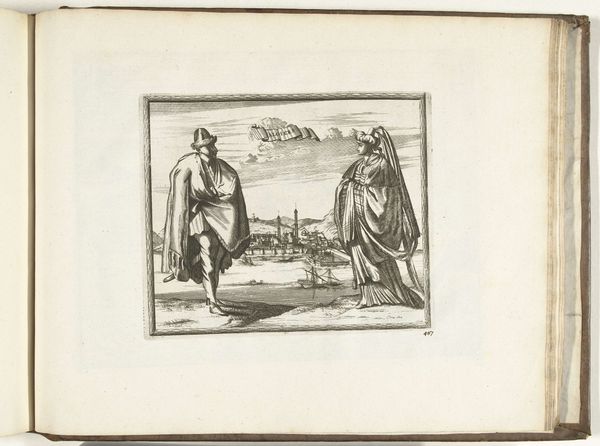

drawing, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

pen sketch

#

landscape

#

ink

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 175 mm, width 209 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This drawing, created in 1726 by Carel Allard, is titled "Inwoners van Pernambuco," which translates to "Inhabitants of Pernambuco." It's currently held in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Well, first impressions: the crispness of the lines is quite striking. It feels staged, almost like characters posed on a proscenium before that flat horizon. Curator: Absolutely. Allard utilized ink to create this engraving, demonstrating impressive control over line weight and texture. Notice the details in the clothing, meticulously rendered, hinting at the social standing of the figures depicted. Editor: The texture is very controlled, I see where you're coming from. The woman's dress, particularly, reads as extravagant. And that parasol feels symbolic – perhaps of status or even protection. Curator: Perhaps, yes, but it's worth considering the social context of its creation. The drawing presents an idealized vision, potentially obscuring the complex colonial realities and power dynamics at play in 18th-century Pernambuco. The printmaking trade reproduces these scenes on a large scale to normalize what is ultimately exploitation. Editor: While your interpretation certainly bears weight when considering the context, focusing solely on that runs the risk of overlooking how meticulously the piece itself has been structured, framed in such a deliberate, contained space. How do we reconcile the beauty of execution with that colonial exploitation? Curator: The material reality of art making doesn’t exist separate from ideology. Consider how this particular method, drawing and engraving, allowed Allard to reach a broad audience with this representation, imprinting these perceptions into the popular imagination. Editor: And yet, within that potentially propagandistic image, there are elements of pure formal brilliance. The dynamic poses of the figures, for instance, lead the eye through a circular path—note that the eye is almost obliged to acknowledge the way the landscape seems almost sketched in as opposed to fully realized, thus drawing your attention immediately to the main figures of the image. It's captivating in its own right, irrespective of what it portrays. Curator: So, are we complicit by appreciating formal qualities alone? Perhaps. But acknowledging the processes—the labor, the intended market, the conditions of production—allows us to critically examine not just the drawing but also the historical moment. Editor: That's a potent point. Ultimately, I suppose both the meticulous details and the overarching narrative force us to engage with layers of meaning, which might, at least, broaden the historical interpretation we give to the art work itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.