Standaard voor de Rembrandt-portefeuille met liervogelmotief 1903

0:00

0:00

careladolphlioncachet

Rijksmuseum

carving, wood

#

wood texture

#

carving

#

arts-&-crafts-movement

#

geometric

#

line

#

wood

#

decorative-art

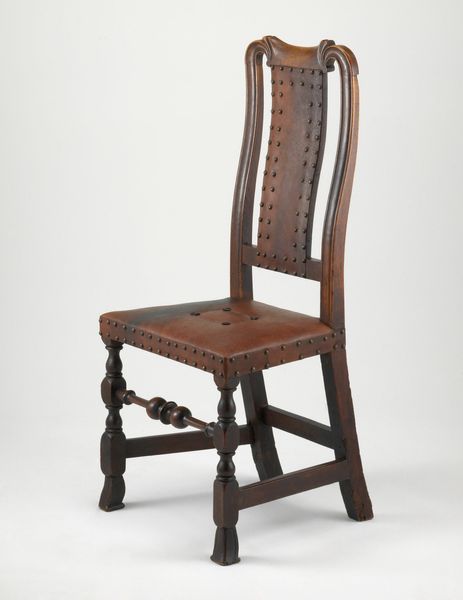

Dimensions: height 140.0 cm, width 72.5 cm, depth 38.5 cm, weight 10.4 kg

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: We’re standing before a rather intriguing object crafted around 1903: a wooden standard designed to hold a portfolio of Rembrandt’s works. Its creator was Carel Adolph Lion Cachet. Editor: It’s strikingly rigid and upright, almost like a piece of furniture aspiring to be a modern sculpture. The carving and the contrasting wood tones give it depth, but I find the subject matter ironic. Curator: The piece exemplifies the Arts and Crafts movement. Think about its dedication to skilled craftsmanship in the face of industrialization, and its aesthetic roots within a broader artistic effort of social reform. Cachet was designing furniture, interiors, and even graphic art for advertising— all with an intense eye for detail. Editor: I notice the emphasis on vertical lines, which appear to elongate and uplift, which contradicts, slightly, my reading. But that carving reminds me of feathers, possibly from the lyrebird, which is an explicit, yet somewhat elusive detail. Is that part of a specific, contemporary trend? Curator: The lyrebird motif speaks to a fascination with the natural world characteristic of the Art and Crafts ethos. The Rijksmuseum holds several other items from his hand featuring a similarly stylized version of this rare Australian bird, hinting at a fascination that recurred through the artist's production. The artist returned again and again to linear depictions from natural phenomena. Editor: So, while the design strives for a functional object, it ultimately prioritizes the decorative. It's as though Cachet imbued what could be a very simple design, and elevates it with a strong aesthetic perspective, referencing exotic places and animals to construct some type of national mythos. It feels quite...charged. Curator: Indeed. I find its visual language inextricably connected to the sociopolitical forces shaping Dutch identity in the early 20th century, caught between an old colonialist outlook and modernist ambition. It also prompts me to wonder: who owned this, and in what sort of space? Editor: I suppose, to me, it's also a symbol of privilege, right? To own a Rembrandt portfolio and then display it in such an elaborate manner is to openly showcase the value and authority embedded in those artistic treasures. Curator: Exactly. And this stand reinforces that social power structure through carefully wrought design. Thank you for sharing that point of view! Editor: Thank you. Reflecting on the politics of display, and the narratives we project onto even functional objects is essential.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.