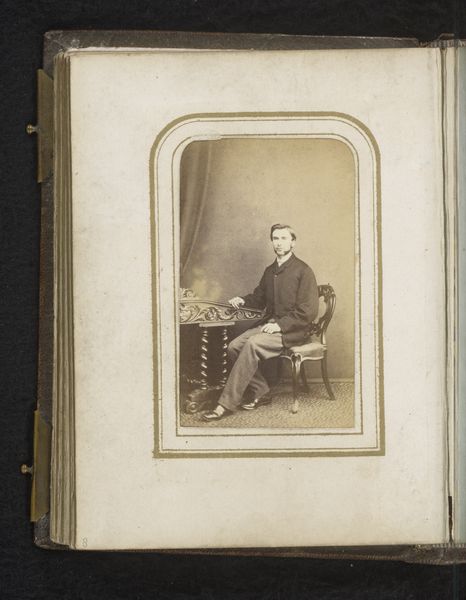

photography

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical fashion

#

genre-painting

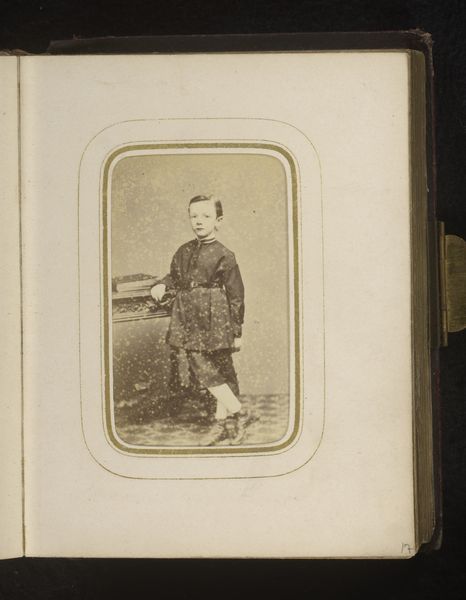

Dimensions: height 101 mm, width 62 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

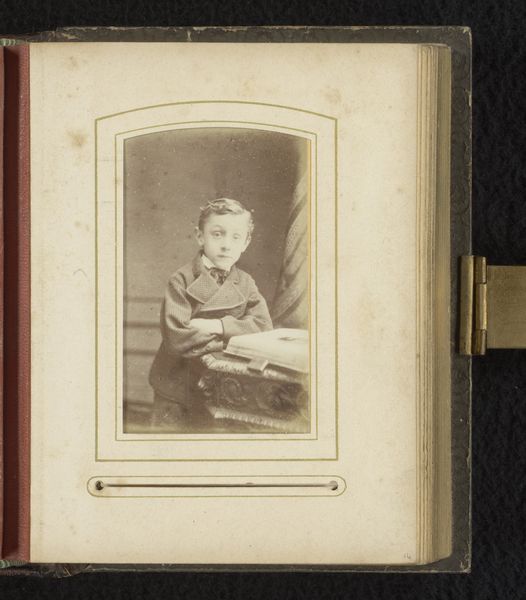

Curator: This is a photograph entitled "Portret van een jongen, zittend op een stoel met wandelstok" which roughly translates to "Portrait of a boy, seated on a chair with a cane", likely created sometime between 1864 and 1878 by Herman Bückmann. Editor: The immediate feeling is one of formality and perhaps constraint. The young boy looks almost… resigned? Curator: It speaks volumes about the era's conventions. Consider the props – the ornate chair, the walking stick – these weren't accidental. They signify a desired status, echoing aspirations within burgeoning bourgeois society. It suggests how image became a tool for social positioning. Editor: And it’s fascinating to consider how carefully constructed the reality is. What material processes and labour went into that chair for example? What's its history? Was this particular photo shoot intended to show a move up the social ladder, in a literal, material sense? The staged nature emphasizes how photography was already being used for fabrication. Curator: Precisely. Photography offered unprecedented control. Families could curate their representation in a way that painted them as prosperous and cultured, sometimes even when reality suggested otherwise. The clothes he wears, the accessories, tell a meticulously constructed story of class. Editor: Looking closer at the photographic process, I wonder about the technical limitations and possibilities. This is before easily reproduced images. So each print carried a significant value. This influences our view – it's a deliberate statement that somebody saw fit to preserve. Curator: Which brings us back to the question of reception. How would contemporary viewers have understood this portrait versus how we interpret it today, colored by decades of shifting social landscapes and photographic conventions? Editor: Exactly. We might be tempted to empathize with the boy, see a loss of childhood. But it may have fulfilled expectations, solidifying connections and belonging. Curator: A photograph is always more than meets the eye—it is enmeshed with social contexts, values, and the mechanics of image-making itself. Editor: Definitely. And teasing out these layered histories embedded within the object lets us rethink both photographic practice, and how materiality shaped historical social norms.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.