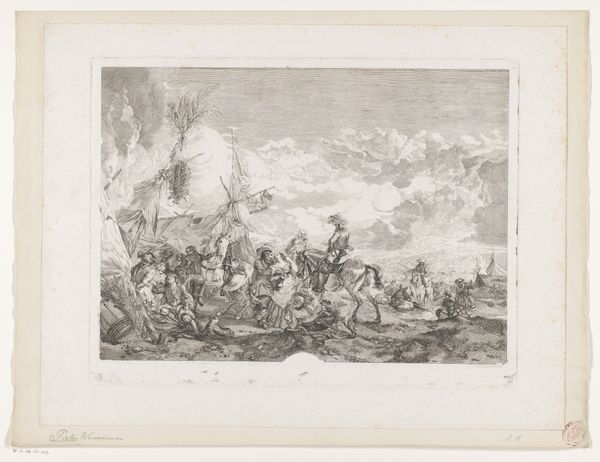

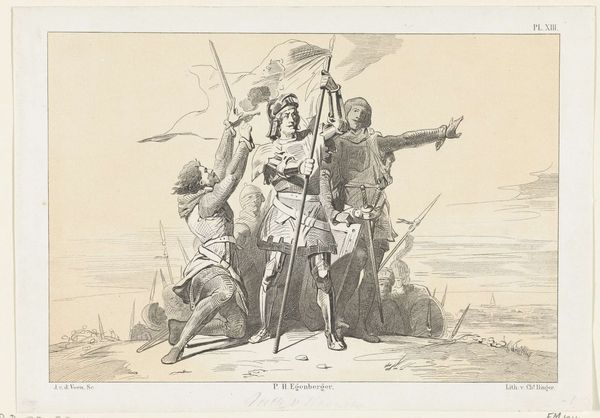

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

group-portraits

#

romanticism

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 650 mm, width 830 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

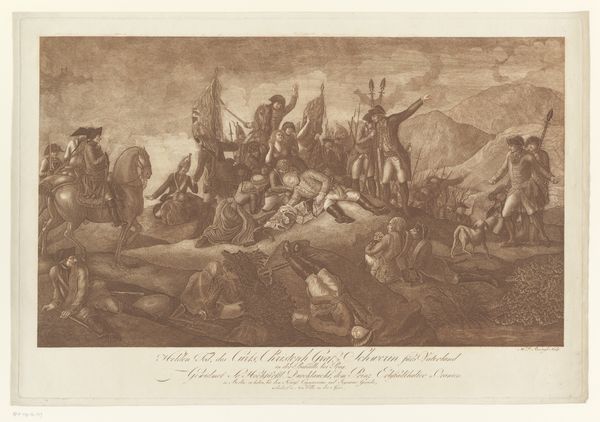

Editor: This is Alexandre Vincent Sixdeniers’ engraving "Napoleon Bonaparte's Crossing of the Alps", dating between 1835 and 1846. It’s incredibly detailed for a print, and depicts a lot of figures on what looks like a perilous climb. What stands out to you? Curator: This work compels me to consider the labour involved in its production. Engravings such as this were not simply artistic expressions but commodities, made by skilled artisans within a specific economic system. Look closely, can you see the repeated lines, the sheer effort required to translate an image onto the plate? Editor: Yes, now that you mention it, the textures are very consistent, which I suppose speaks to the mechanisation of labour and printing processes in this era? Curator: Precisely! Consider, too, who consumed such images. These prints, often reproduced in multiples, democratized art. They served to spread particular political messages – in this case, Napoleon's heroic image – among a wider audience, reaching even those who could not afford paintings. Does the image challenge traditional distinctions between fine art and something merely reproducible, functional, or ‘common’? Editor: Definitely. While romanticized, it’s not something only the elite could enjoy. Curator: Consider further, the materiality of the engraving itself – the copper plate, the ink, the paper. All these elements have a social life, circulated within networks of production and exchange. What could have been the effect of these materials to its production and Napoleon’s legacy? Editor: The wide reach of the prints certainly cemented Napoleon's image and the historical perception of his achievements through strategic dispersal to the masses. It brings a totally different point of view about the role of a historical artwork such as this, beyond the visual appeal. Curator: Precisely. By attending to the materiality and mode of production, we can gain a more grounded understanding of its function and place within 19th century society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.