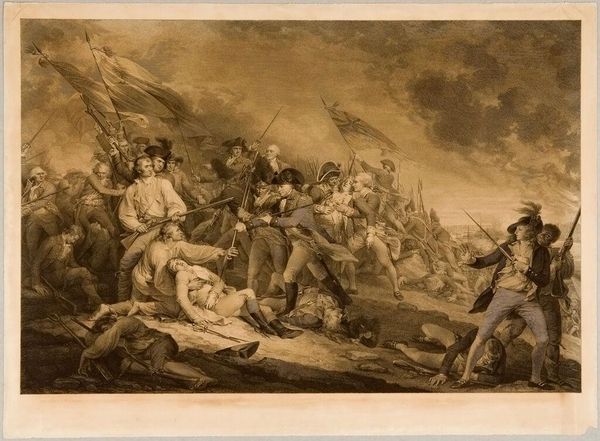

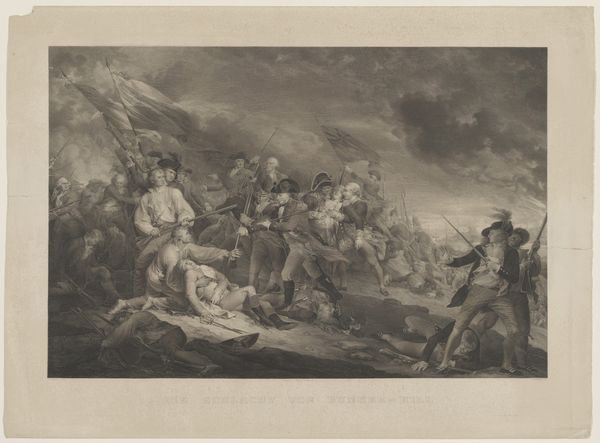

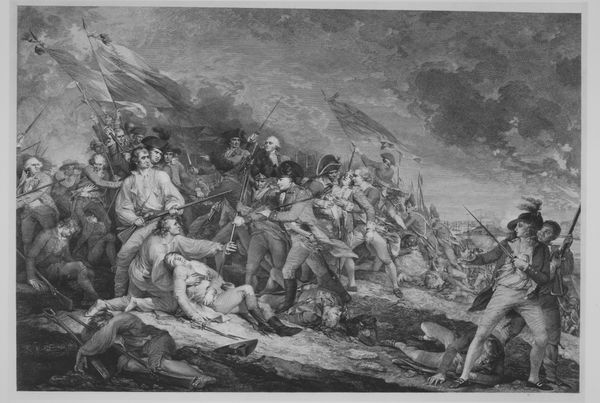

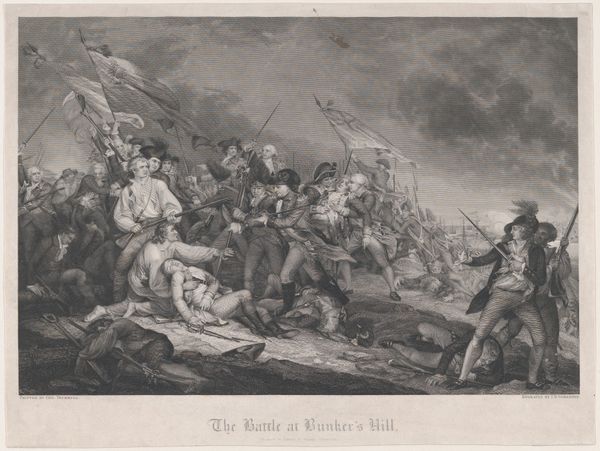

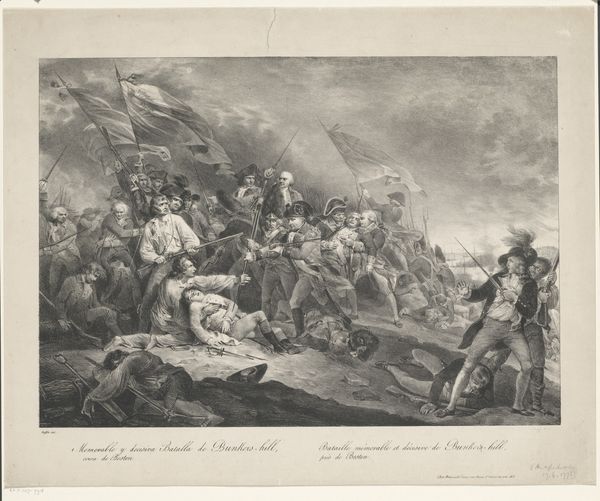

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 580 mm, width 799 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this print, I immediately get a sense of swirling chaos mixed with determined resolve. It’s Johann Gotthard Müller's "Slag bij Bunkers Hill, 1775," made in 1798, an engraving that captures a pivotal moment during the American Revolutionary War. Editor: Chaotic is right! Like being tossed into a dust devil of powdered wigs and bayonets. So much movement! I’m struck by how the composition almost throws you into the thick of it, as if you are dodging the smoke and steel. Curator: That’s a great point about the composition. Müller’s artistry uses that whirlwind of bodies and intense expressions to pull the viewer right into a battle fraught with historical and political weight. The Battle of Bunker Hill, though a tactical victory for the British, galvanized American resistance. The high cost to the British showed the resolve of the colonial militia. Editor: Resolve is one word for it; madness another! Look at the determination, but also the agony etched onto these faces. It is amazing how an engraving, without relying on color, conveys such intense drama. The lines are so dense in places they appear almost black. Curator: Müller's exceptional control of the engraving medium helps intensify the dramatic impact of the historical subject. Engravings like this circulated widely. As prints, they served to inform public opinion, commemorate significant events, and contribute to the burgeoning sense of national identity both in America and, to some extent, in Europe, which watched the revolution with interest. Editor: Interesting that he made this almost 25 years later... So many competing accounts of this very murky battle must have been flying around at the time, and Müller’s had to reckon with those to produce something his audience would see as true. Curator: Absolutely, Müller wasn't simply documenting; he was shaping historical memory. And these depictions played an important role in how both sides understood the conflict. It reinforced a particular narrative, an early example of visual propaganda. Editor: That makes me think, what is lost when history becomes art? Perhaps the gritty reality… or perhaps what is found is a sense of shared identity and purpose, that really lingers beyond all the smoke and gunfire. Curator: A fitting reflection, wouldn't you say, on a conflict defined by such enduring ideological resonance? Editor: Yes. Ideals made tangible in ink, and gunpowder made somehow… elegant?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.