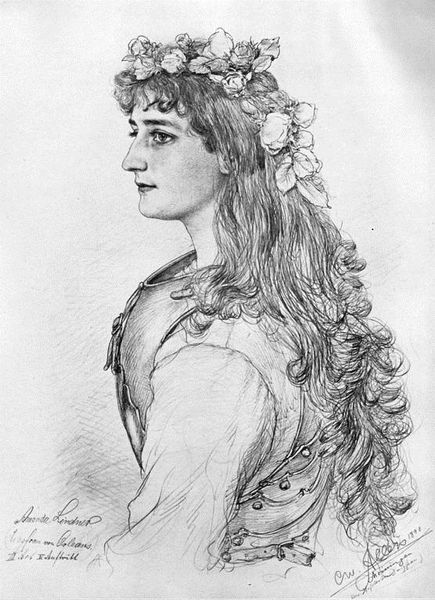

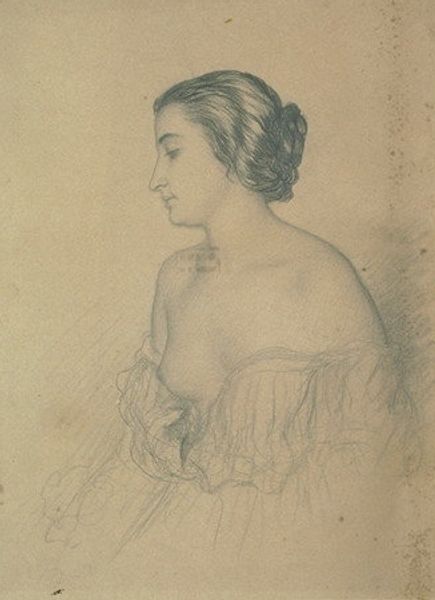

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

facial expression drawing

#

narrative-art

#

portrait image

#

pencil sketch

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

male portrait

#

portrait reference

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

men

#

portrait drawing

#

facial study

#

facial portrait

#

academic-art

#

digital portrait

Dimensions: 6 1/4 x 5 1/8 in. (15.9 x 13 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Before us, we have "Holy Eyes" from the McGuire Scrapbook, a pencil drawing dating back to 1850. It's a striking example of Romantic portraiture currently held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: There’s a softness to the light in this sketch; it gives the figure an almost ethereal quality. I notice the way her gaze is directed upward, as if contemplating something beyond our world. Curator: Indeed. The artist, Thomas Story Officer, employs a delicate touch, capturing the sitter’s introspective mood and imbuing her with this sense of virtue or devotion. The placement of the Holy Bible hints at her religious beliefs and their importance in the 19th century American life. It mirrors, I think, society's attempt to negotiate women's roles through piety and moral guidance. Editor: Absolutely, the book feels more like a prop, doesn't it? I am interested in unpacking the visual rhetoric employed here, particularly around how feminine ideals are constructed. The almost performative way the 'Holy Bible' is embraced is revealing, like piety itself, becomes a staged aspect of this feminine identity. What's going on beneath the surface? Curator: Well, we see academic influence—the careful rendering of form—merged with Romantic ideals about emotion and inner life, reflecting the conventions of the period's artistic production and its ties to social norms. You get a sense of how portraiture became entwined with identity construction. Editor: Right, and for whom were these identities being constructed? Surely not for the woman, but for patriarchal validation, right? This image is part of a legacy of artistic portrayal that both confined and celebrated women within specific parameters, pushing for an understanding of her, yet limited by its narrow portrayal. I am critical about celebrating portraits like this because what are we celebrating about her? Curator: These kinds of questions help us confront the past with open eyes. Seeing art this way provides insights to both art's formal elements and also its lasting and often unacknowledged role in influencing cultural mores and ideals. Editor: Agreed. Examining works like "Holy Eyes," and the historical context in which they exist, gives the capacity to recognize and discuss how such representation has been manipulated throughout history. The ongoing reinterpretation—the discourse that takes place—continues to grant power in defining cultural ethos.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.