graphic-art, lithograph, print, poster

#

graphic-art

#

art-nouveau

#

narrative-art

#

dutch-golden-age

#

lithograph

# print

#

figuration

#

line

#

symbolism

#

poster

Dimensions: height 348 mm, width 252 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

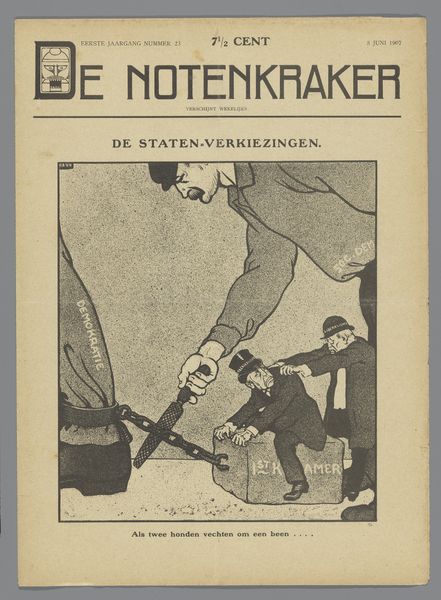

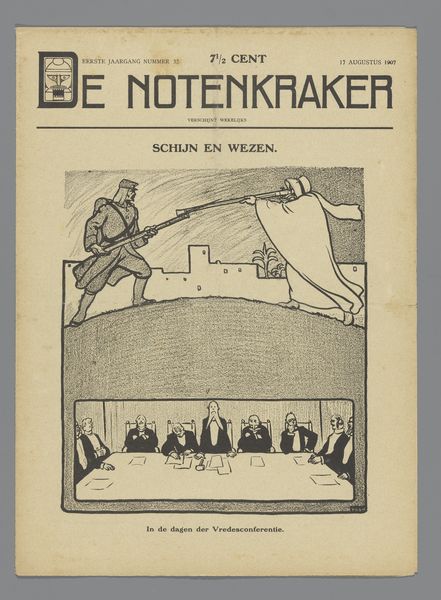

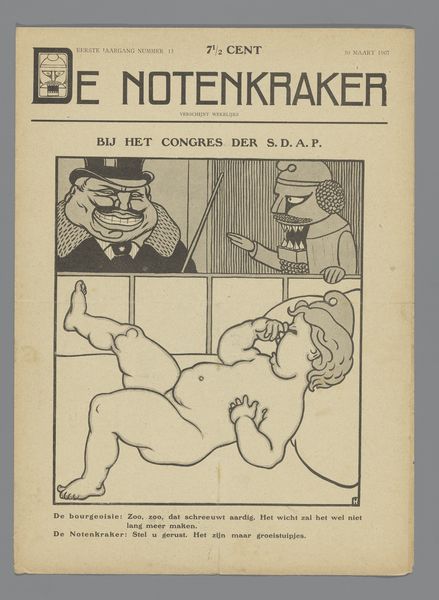

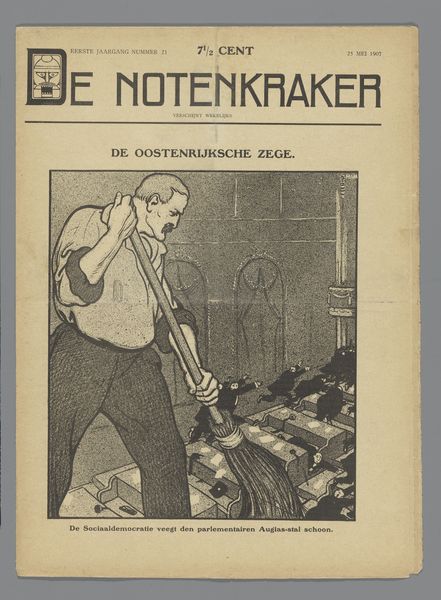

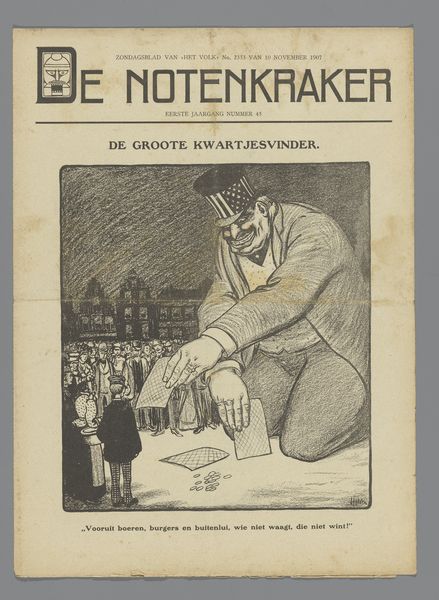

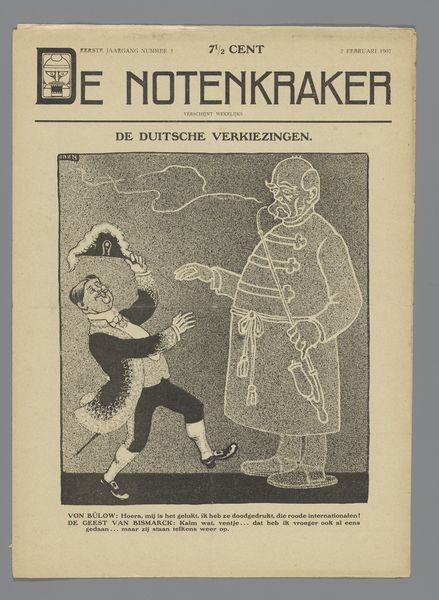

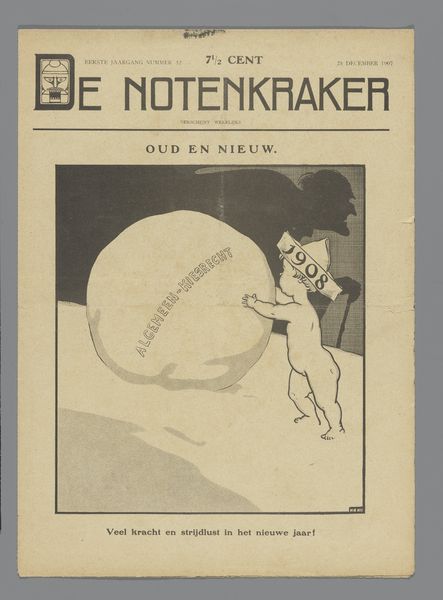

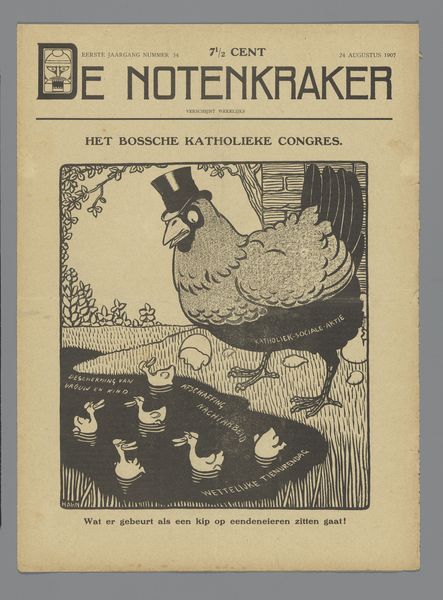

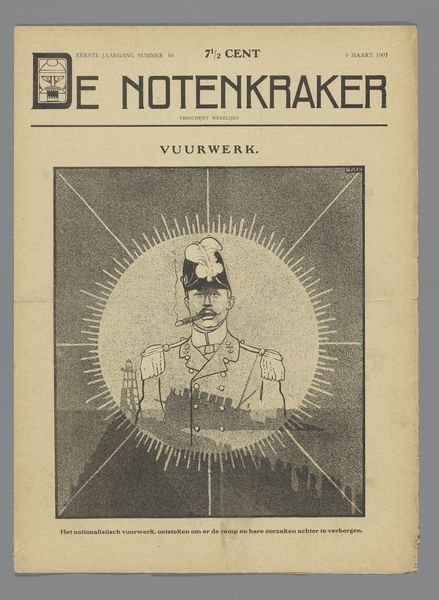

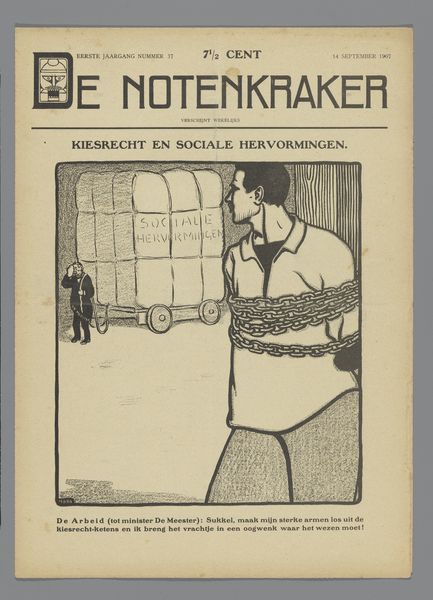

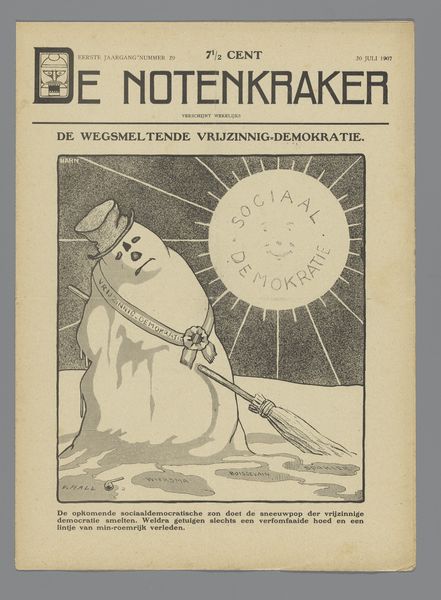

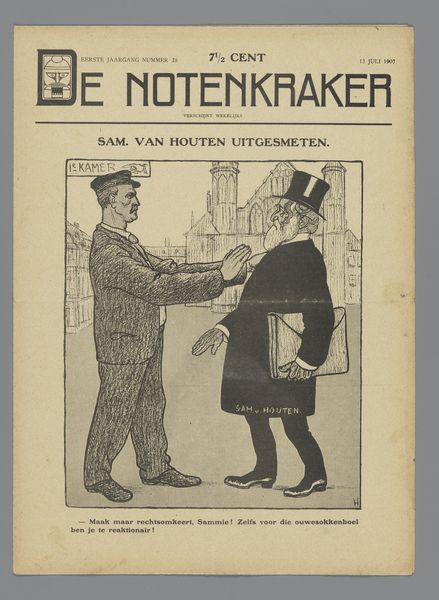

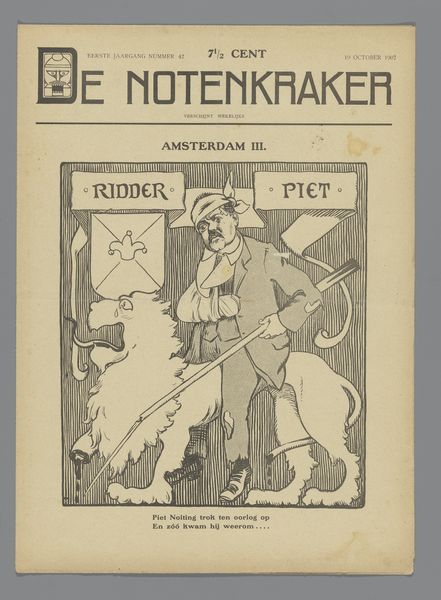

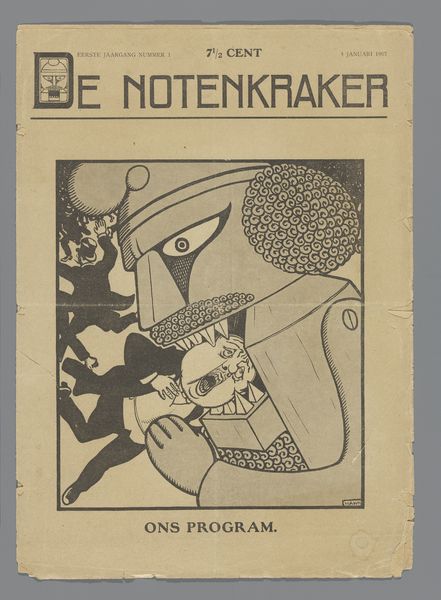

Curator: What strikes me immediately about this lithograph, from possibly 1907, titled "De Notenkraker, 18 mei 1907 / Eindhoven" by Albert Hahn, is the clear depiction of societal strain and struggle. It's quite somber, with these two burdened figures depicted, contrasting the one perched precariously above the one stooped over. Editor: I'm most drawn to the production of this image as a political poster. The rough texture from the lithographic process—the gritty application of ink—enhances the message of toil and injustice. What specific materials were accessible, and how does that influence its mass production? Curator: Mass production implies accessibility, especially when you consider this image appeared on the cover of a satirical magazine, indicated at the top. The figures and their positions, especially given the period when tensions of labor movements were brewing, symbolize something very powerful. The man below bearing the weight—seemingly representing the working class—supports the oppressor on top. Editor: Indeed. The contrast is telling, and Hahn’s choices about who holds weight in this economic architecture are clear. It speaks to the artist’s hand as a craftsperson participating and reacting to the larger system, rather than floating above it. Is the figure above rendered as parasitic? Curator: Yes, that’s certainly what the artist evokes! His suit and obesity suggests prosperity from the expense of those he stands upon. But notice he seems equally burdened. And below this evocative illustration reads, “Zelfs in het duister kiemt nieuw leven!”, translated, "Even in the dark, new life germinates!" Symbolism through textual reference adds another dimension. Is this darkness that of social depression? Editor: The line evokes the tension between what labor generates—value—and how unequally its rewards are dispersed, reflected in this single print. One wonders about distribution of labor and class consciousness at the turn of the century, especially the economic shifts felt in Eindhoven, a place printed distinctly below the masthead! Curator: Absolutely. Seeing it within its context opens further the multiple symbolic layers and its original significance. Editor: For me, exploring art as an act of production allows us to consider it an object in dialog with its own creation and societal reception, providing crucial material and symbolic links in social dialogue.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.