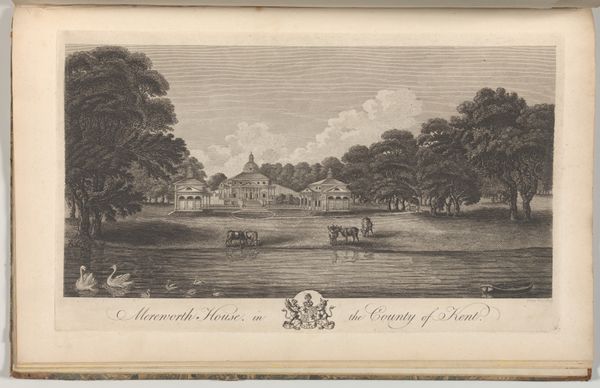

Merenorth House, in the County of Kent, from Edward Hasted's, The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent, vols. 1-3 1777 - 1790

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching, engraving

#

drawing

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

neoclassicism

# print

#

etching

#

book

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

engraving

#

building

Dimensions: Book: 17 5/16 × 11 × 13/16 in. (44 × 28 × 2 cm) Sheet: 16 15/16 × 10 5/8 in. (43 × 27 cm) Plate: 10 1/16 × 14 in. (25.5 × 35.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have "Merenorth House, in the County of Kent," an engraving by Richard Bernard Godfrey, dating from between 1777 and 1790. It comes from Edward Hasted's "The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent." Editor: My first thought is of understated elegance. The toned paper, the meticulous lines of the etching—there's a real sense of craft here. Almost feels like a lost world, observing this grand house in the English countryside. Curator: Indeed. These county surveys served a very specific social purpose. They documented land ownership and status, solidifying the position of the gentry within the broader societal structure. Godfrey's work, in particular, highlights the increasing interest in neoclassical ideals and architecture. Editor: The choice of engraving as a medium feels quite deliberate, too. Consider the labour involved in creating this level of detail and consistency across multiple prints. It speaks to the growing market for these types of visual representations of property. There's even the texture, the almost tactile feel of the light pencil work that emulates the very materials it seeks to portray. Curator: Precisely. The landscape, bathed in a gentle light, emphasizes the tranquility and prosperity associated with land ownership. It evokes a vision of England deeply rooted in its aristocratic past. Look closely at how Godfrey uses perspective to position Merenorth House as a dominant, yet harmonious, feature within the scene. It’s all about reinforcing social hierarchy through idealized imagery. Editor: The print almost hides labor behind this tranquil image, too. Consider the actual agricultural labour needed to support a family in a great house. That connection to raw materials is entirely abstracted. The print transforms property into art. Curator: I agree, the print becomes a carefully constructed commodity in itself. It is something exchanged, collected, and used to reflect prestige upon the owner. A status symbol broadcast across the volumes. Editor: It leaves me considering what labor might have remained invisible. Both within the grounds depicted and in the processes required to arrive at the finished engraving. It offers so much about the cultural landscape of the period, once we move past that surface impression of tranquility. Curator: And to recognize how prints such as these actively shaped the perception, and indeed the value, of property and social standing. Editor: Absolutely. The artist’s contribution is undeniable, adding value through skillful engraving.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.