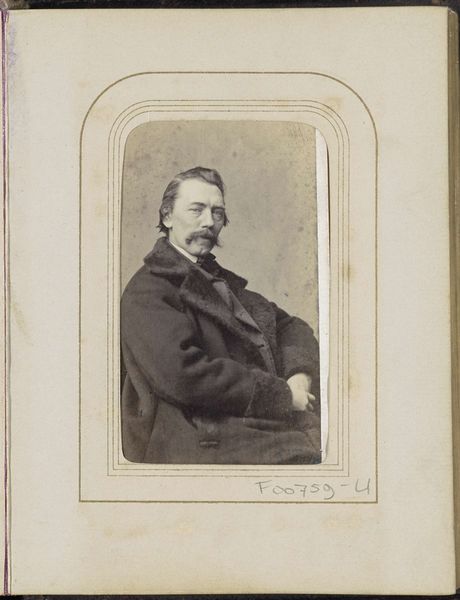

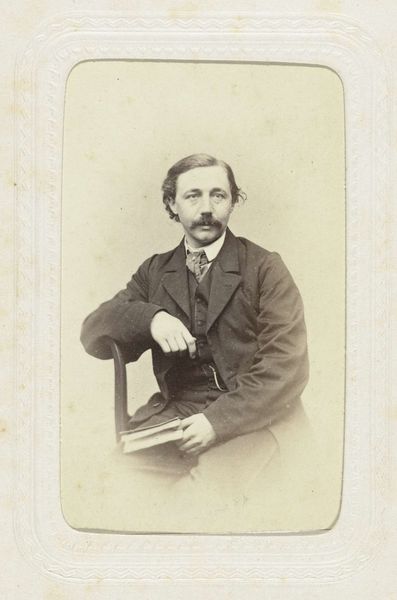

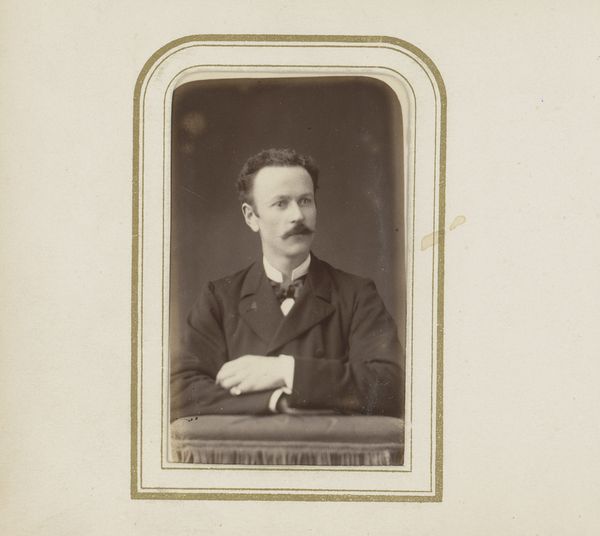

Dimensions: height 83 mm, width 50 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is an albumen print from 1861, titled "Portret van een zittende man met snor," or "Portrait of a seated man with mustache" in English, credited to Charles D'Hoy. Editor: He certainly cuts a figure, doesn't he? The first thing that strikes me is the almost theatrical staging. There's a quiet intensity about his gaze, a stillness, but I wonder about the context of such images. Curator: Precisely. By the mid-19th century, photography had become a potent tool for shaping social identities, even in a newly democratized manner. Though portraiture was once a privilege of the upper classes. What stories do these carefully constructed appearances obscure or reveal? Editor: The democratization angle is definitely a piece, especially since photography was relatively more accessible. But look at his attire. This is not the everyday person. This suggests perhaps bourgeois aspirations? It prompts reflections on who was considered worthy of immortalization, doesn't it? How are the excluded kept outside this frame? Curator: That tension is pivotal. The rising middle class strategically leveraged photographic portraiture to signal respectability and integrate themselves into the cultural and political spheres. Note how D'Hoy employs conventional portraiture styles that further affirmed such new positions of social power. Editor: Agreed. It is clear he aims to present respectability. It's very proper but I can't help but feel a melancholy or hint of sadness beneath the surface. Perhaps an awareness of social anxieties. The photograph can both project and subtly betray inner states of being. Curator: Indeed. I see it as representative of the epoch in that way. Photography’s capacity to portray reality heightened expectations but also created spaces to stage and manage visibility—all caught in this negotiation, even anxiety. Editor: And there is an emotional vulnerability, despite all the artifice. It makes us want to connect with the historical human subject more deeply. It's those unspoken narratives where social power truly begins to move and work its own agenda. Curator: Thank you. I agree it offers much for contemplation, and further discussion in the public arena. Editor: My pleasure. I believe with that reflection, our listeners have been armed to engage.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.