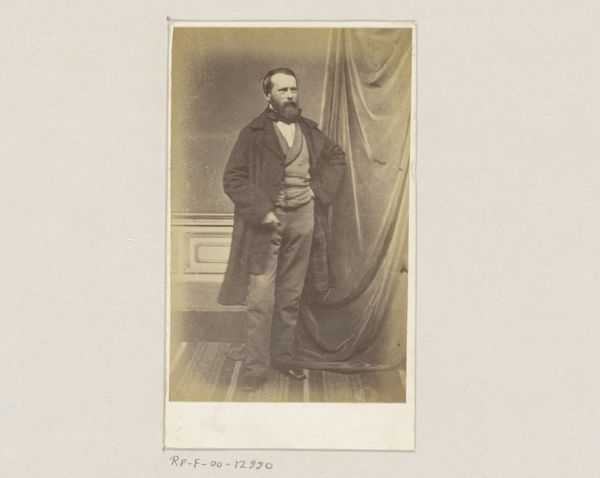

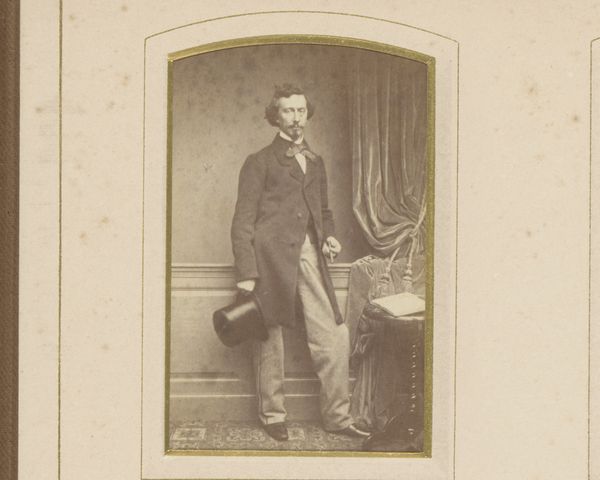

photography

#

portrait

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

19th century

#

realism

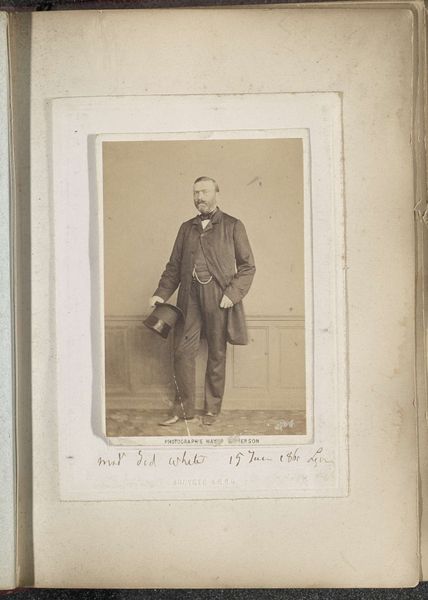

Dimensions: height 83 mm, width 50 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here at the Rijksmuseum, we have an albumen print titled "Portret van een staande man met hoge hoed," dating from 1860 to 1894, attributed to Ghémar Frères. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: It’s austere. The gray tones flatten the figure somewhat, but it’s the formality of the pose that really strikes me. There is a tension between what is revealed and what is concealed. Curator: I see it as a study in controlled composition. Notice how the vertical lines of the curtain, the wall paneling, and the man himself create a sense of stability. The slight curve of his coat mirrors the arc above, in a clever alignment that stabilizes the pictorial field. The high hat serves as a counterpoint, drawing the eye upward. Editor: I am interested in the choice of albumen as the printing method. What was its particular appeal during this period? And albumen requires a very thin coating of egg whites – a messy and smelly affair to produce these photographs! What does the materiality of that production suggest to us about this era’s values surrounding portraiture? Curator: Albumen prints allowed for finer detail and a wider tonal range, providing a degree of verisimilitude then unmatched, enhancing the image. The high degree of crispness amplifies the reading of the subject as an individual, worthy of prolonged contemplation. Editor: Precisely, this individual, like many from the burgeoning middle class, understood that this particular photographic method provided an aura of status. By literally embedding oneself in egg, one created an elaborate symbol of class aspiration through a novel technology that elevated the individual above the mess of the social fabric. Curator: I hadn't considered the social aspirations encoded in the albumen print itself. Interesting. Editor: In that way, the photograph almost ironically gestures beyond the constraints of the figure standing there—the materiality speaks loudly to production, class, and the performance of one's place within the 19th century. Curator: Indeed. It's a testament to how even seemingly straightforward portraits can reveal intricate layers of meaning when examined through different lenses.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.