#

portrait

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

coloured pencil

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 196 mm, width 137 mm, thickness 16 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

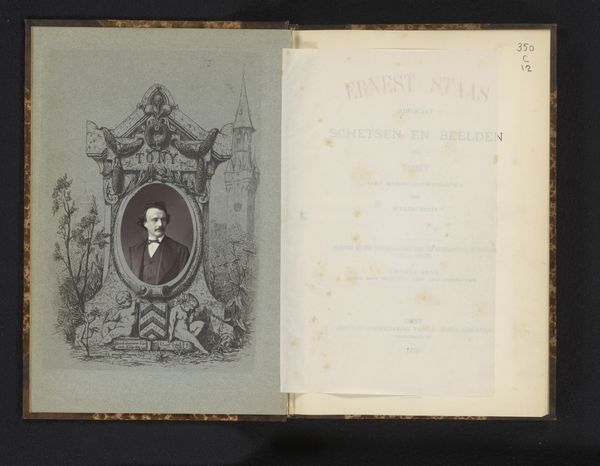

Curator: Oh, there’s a wistful feeling just looking at this. A closed book, yet an open invitation… faded like a dream. Editor: We're looking at the book “Bladeren en Bloemen: Poezy” or "Leaves and Flowers: Poetry" by Jan Jakob Lodewijk ten Kate, circa 1870-1875, currently held in the Rijksmuseum. I'm struck by how much the construction of this object, of books like this, speaks to Victorian-era reading habits and book production, but that subdued tone really hits home. Curator: Exactly. The faint portrait pasted inside is haunting, like a memory trying to surface. Was it intentional, this subdued effect, or simply the work of time? Editor: The discoloration points towards degradation of materials, perhaps acidity in the paper or adhesive reacting over time, a sad fact when you think about how industrialization introduced chemicals in paper production that harmed so many printed materials. Curator: Even in its fragility, there’s a story of enduring affection, you know? The physical wear and tear tells us someone held this close, cherished these verses, leaves, and flowers. Editor: Absolutely, but look closely – you can also tell so much about the publisher’s printing process. The layout, the font choices, even the quality of the binding – all tell a material story. Who was this publisher A.W. Sijthoff of Leiden and what was the landscape of book production and consumption in the Netherlands during the period. Curator: Material, spiritual – both bound together, I think. A collaboration across time and touch. It is what moves you. Editor: Agreed, but that book traveled along very defined networks of distribution, production, and eventually consumption that still matter, these factors shape value as much as beauty. Curator: It seems to beckon me into a vanished parlor, filled with whispered verses and pressed blooms. The soul in that moment of history must surely remain intact through the verses written by Ten Kate. Editor: Indeed. Seeing it helps us to visualize literary practices during that time. It’s a reminder to appreciate the book not just as art, but as evidence of a larger history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.