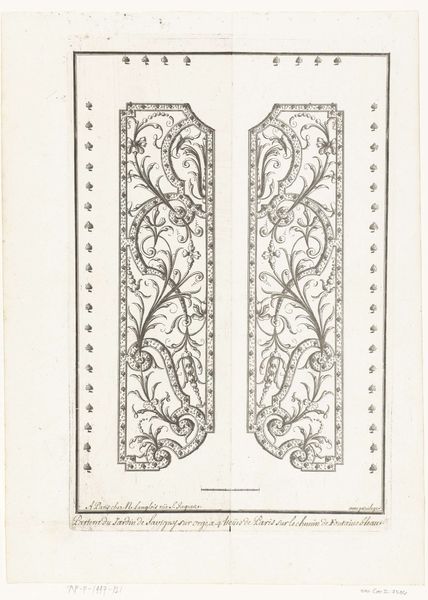

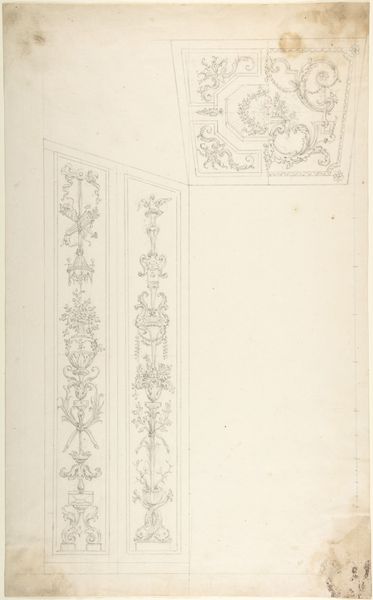

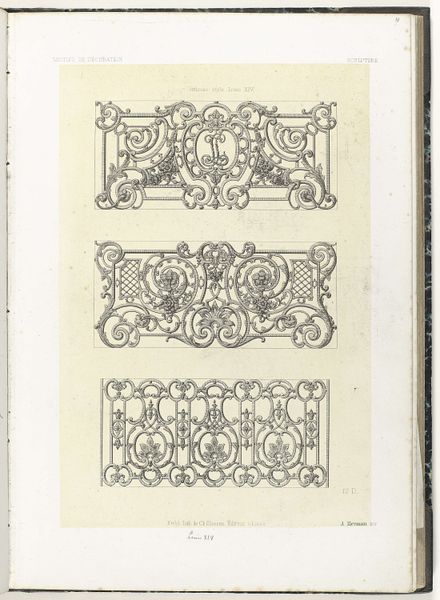

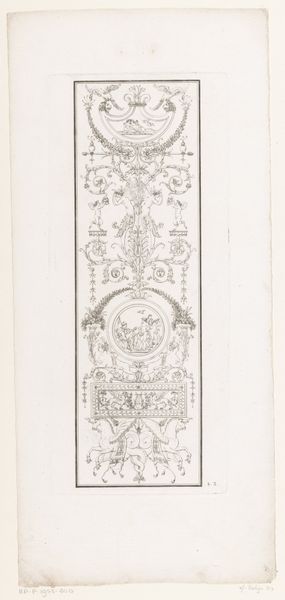

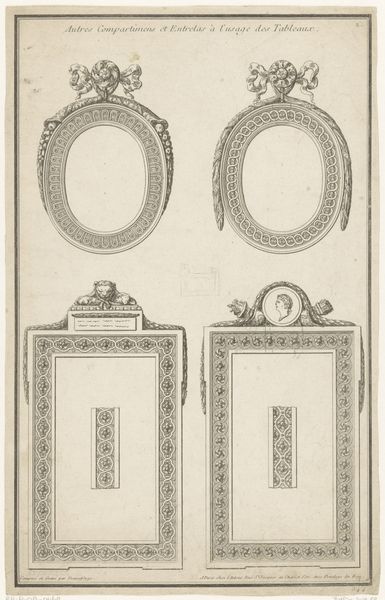

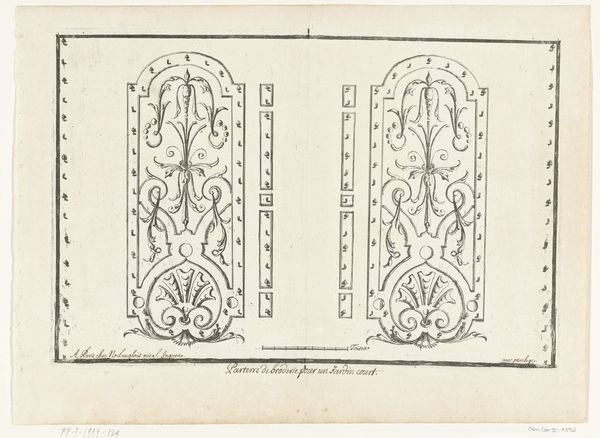

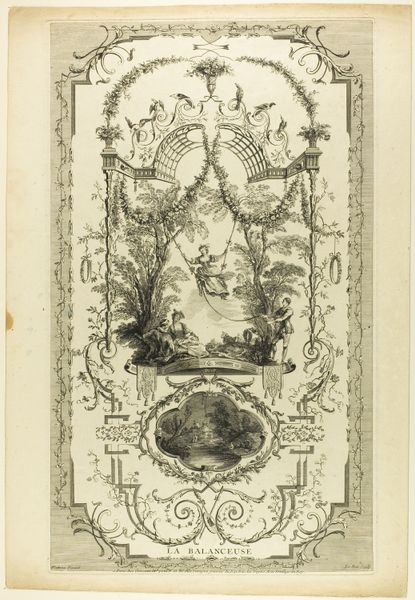

drawing, paper, engraving

#

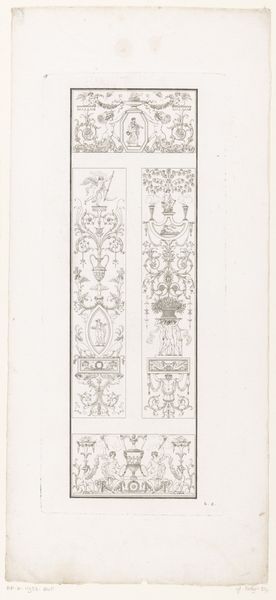

drawing

#

baroque

#

landscape

#

paper

#

geometric

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 320 mm, width 228 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This delicate drawing, "Parterre van tuin van Savigny," an engraving by André Le Nôtre, was made between 1670 and 1680. It depicts a garden plan with ornate, geometric designs. I am immediately struck by the precision and the seemingly endless repetition of the floral patterns. What's your take on this piece? Curator: Well, let’s consider the conditions of its creation. This wasn’t simply about aesthetic beauty. Le Nôtre, designing gardens for the French elite, was engaged in a large-scale manipulation of nature for consumption. The materials -- the plants, the soil, the labor of gardeners – were all resources marshalled to produce this specific vision. What do you notice about the implied labor within the geometric structures? Editor: It's interesting how you frame it as manipulation... the sharp angles feel very manufactured when considering it is a garden! The shapes and details require lots of maintenance and, well, labour. How would it have functioned in Baroque society? Curator: Exactly! This represents control – control over nature, and the control exerted through wealth. Baroque gardens weren't just for looking; they were stages for social performance. How does the reproducibility of an engraving, a medium designed for circulation, complicate our understanding of something so exclusive? Editor: I never considered that. Making it an engraving allows the design to be disseminated. Does that democratize the design to a certain degree? Curator: Perhaps in theory. More directly, engravings aided in standardizing luxury. Le Nôtre’s designs could inspire other wealthy patrons and garden designers across Europe, expanding his aesthetic control. They weren't mere pictures; they were templates for material appropriation, wasn't it? Editor: I guess seeing it as a drawing is somewhat misleading – it’s more like a blueprint or manual for labour. I can understand the connection between materials, making and social class now! Curator: Yes, the drawing becomes secondary to its instrumental role, showcasing how artistic production is intrinsically tied to resource management and societal power. We moved away from an emphasis of “what” the drawing shows towards the socio-political conditions of "how" and "why" the image got created.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.