print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

historical photography

#

portrait reference

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 221 mm, width 161 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

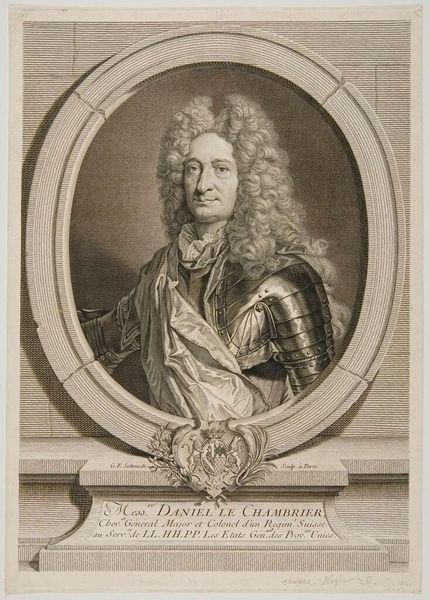

Curator: Before us, we have a print dating from after 1708, housed right here at the Rijksmuseum. It's a portrait of Anne Jules de Noailles, created by Pieter van Schuppen. Editor: My immediate impression is one of restrained power. There's a weight, a gravity to the subject, emphasized by the density of the engraving itself. The man seems almost overwhelmed by his elaborate wig and armor, yet he retains a piercing gaze. Curator: Absolutely. Van Schuppen captures the essence of the Baroque era, an era marked by grand displays of status. It’s worth noting how portraiture, and prints particularly, functioned as political tools in this period, circulating images of power. Anne Jules was a very important military figure during this period, and the artistic composition shows his place in society. Editor: The armor becomes a symbol, doesn't it? It transcends mere protection and morphs into a representation of lineage and societal expectation. Even the elaborate curls convey an almost architectural sense of authority. They add up to this... edifice of power, literally crowning the man. And consider the frame – it’s not merely decorative, it's filled with inscription and suggests layers of meaning that build up Noaille's heroic character. Curator: Precisely! These details also functioned as historical documents and as disseminators of cultural values and expectations. What is striking for me is that his lineage is what matters most here. It shows society that one’s place has already been chosen, which I would argue becomes a major factor to explain the rise of the French Revolution later on. Editor: The inscription is an important cultural feature of this kind of portrait. Even though we can't necessarily understand it today, it is definitely there for a reason and its purpose, if known, should be carefully studied for a more holistic reading. Curator: Definitely. Overall, a glimpse into the workings of power and the mechanics of image-making in the 18th century, where visuals weren’t just depictions but statements. Editor: It's a reminder of the carefully constructed visual languages used to perpetuate certain narratives about class and status.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.