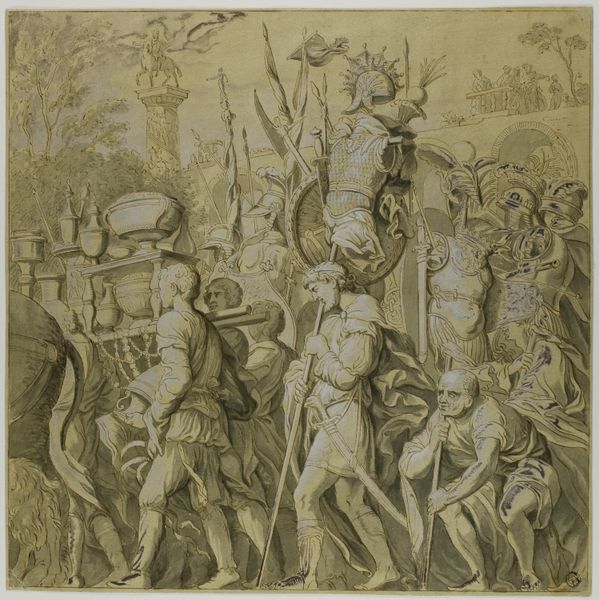

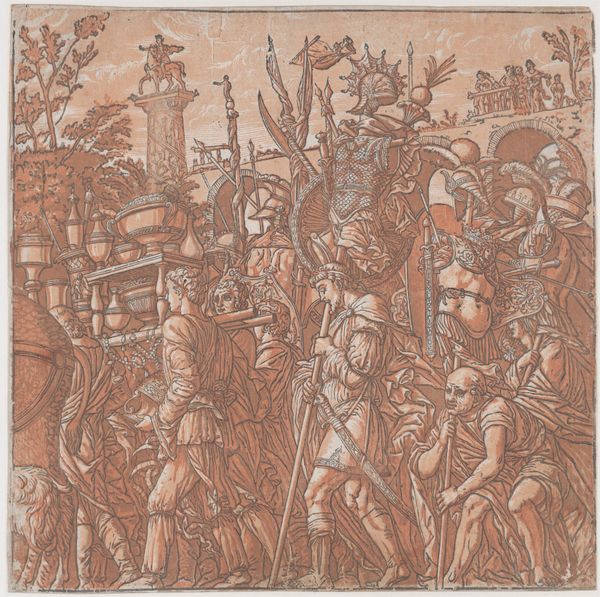

Triumphs of Julius Caesar: Canvas No. VII c. 18th century

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

high-renaissance

#

narrative-art

#

ink painting

# print

#

figuration

#

paper

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

history-painting

Dimensions: 370 × 373 mm

Copyright: Public Domain

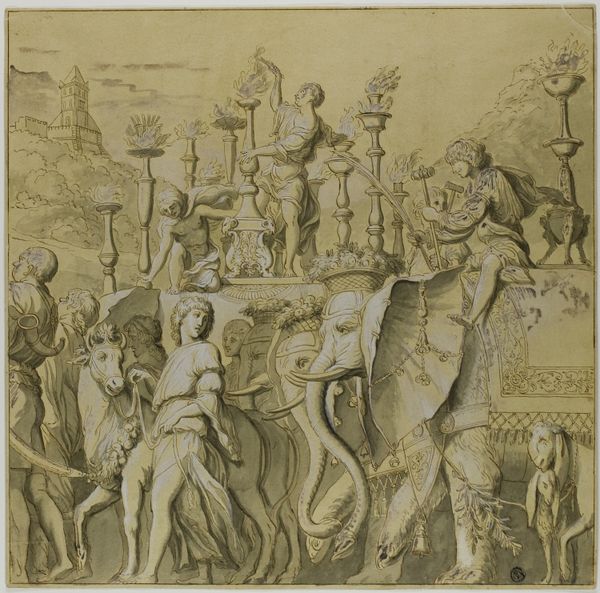

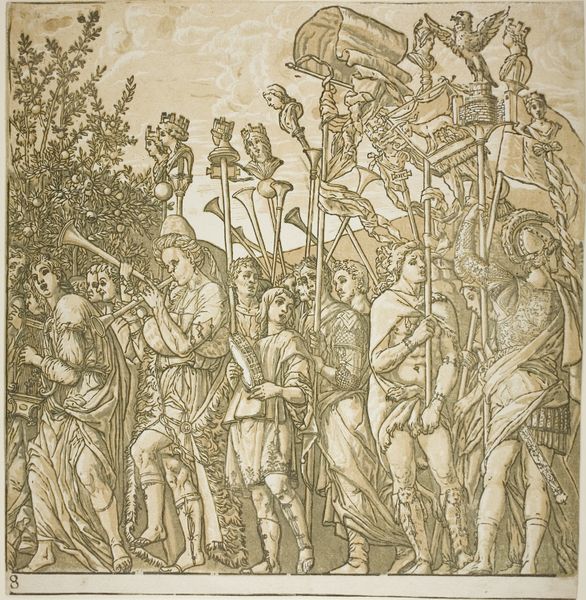

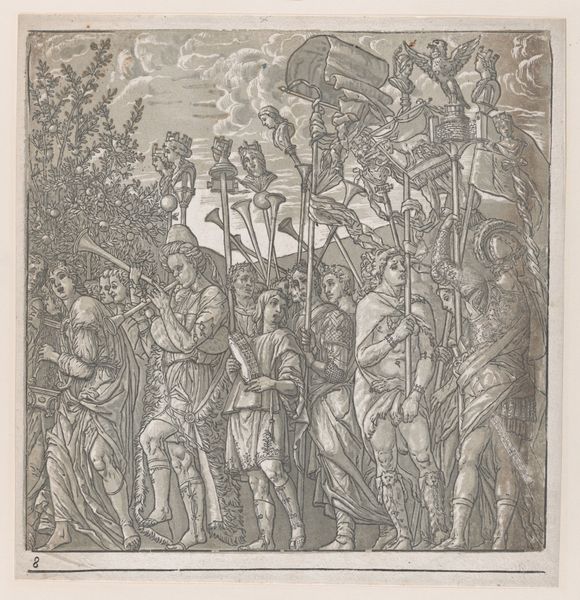

Curator: Welcome. We're standing before "Triumphs of Julius Caesar: Canvas No. VII," a drawing from around the 18th century currently held here at The Art Institute of Chicago. The piece is thought to be after Andrea Mantegna, rendered in ink on paper. Editor: My first thought is how grand and ceremonial it feels, almost like a meticulously planned procession. The monotone ink makes it timeless, while the detail suggests an epic tale waiting to unfold. Curator: Absolutely. These triumphal scenes were highly significant in both Roman and Renaissance cultures, representing military prowess and imperial power. Consider Mantegna’s own series, painted around 1485-1492: those depictions of Caesar's victories were a profound statement about authority and legacy. Editor: It strikes me, though, how these triumphs—celebrated through art and performance—sanitize the brutal realities of conquest. There’s a distinct lack of the cost of war—the enslaved, the displaced—just triumphant figures. Who benefits from these historical representations? Curator: That’s a crucial point. These images functioned within a complex social fabric, reinforcing existing power structures. They provided a narrative frame through which the elites of Mantegna's time could connect themselves with Roman Emperors and assert dominance. Editor: I notice also how stylized the figures are, almost like actors playing roles in a grand play. The trumpets, the banners, all the performative elements underscore the curated nature of power. And whose stories get lost or erased to allow that to remain in focus? Curator: This is history written and visually proclaimed by the victors, yes. Understanding the political environment during the Renaissance clarifies why rulers such as Caesar were used as tools in cultural production, to solidify legitimacy of a contemporary ruler by association with a figure of history. Editor: Indeed. This drawing challenges us to not only admire the artistic skill involved, but also consider the ideological project it’s participating in. Whose narratives are amplified, and whose are silenced, in the creation of heroic legacies? It makes me want to look past the image to reveal unseen narratives. Curator: By reflecting on the purpose of these works, both during the Renaissance and afterward, we gain an awareness of how such visuals work to influence perspectives and manipulate beliefs—how imagery and its place in cultural narrative is power. Editor: Precisely, and this helps us consider the complex legacy that pieces such as this inhabit today, when ideas around nationhood and imperialism continue to shift. Thank you for pointing the direction towards these discussions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.