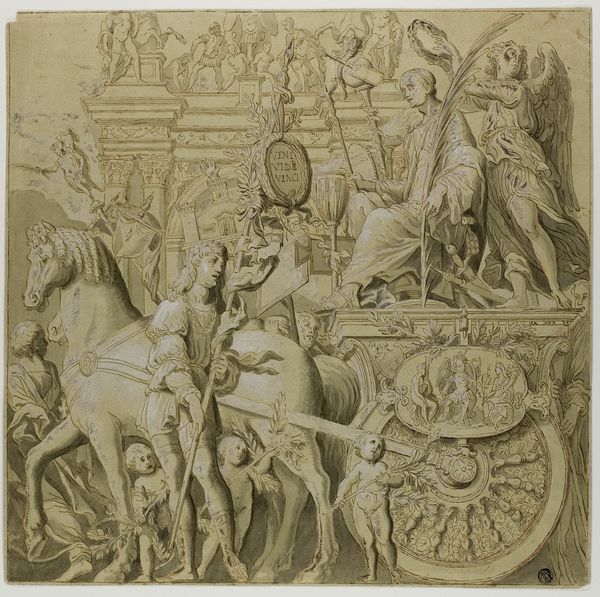

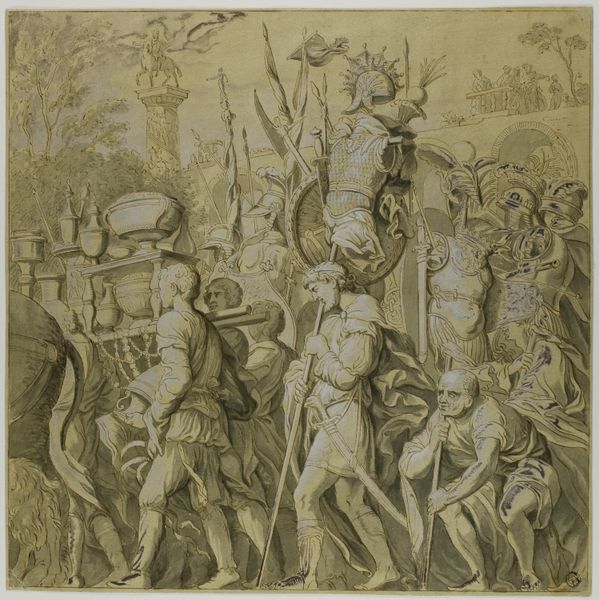

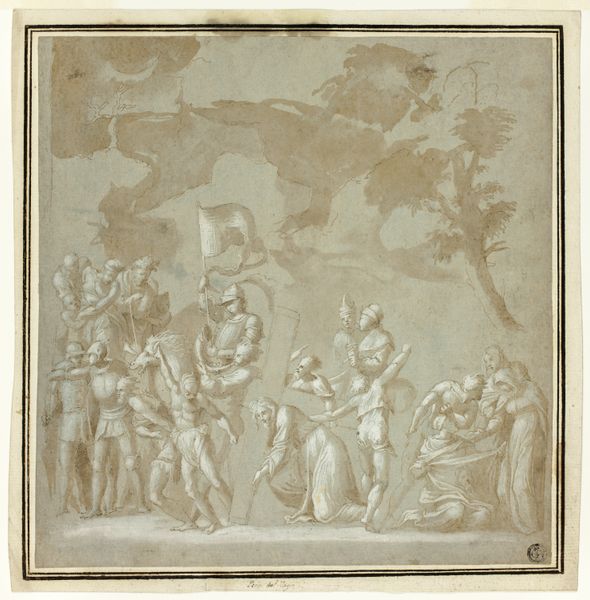

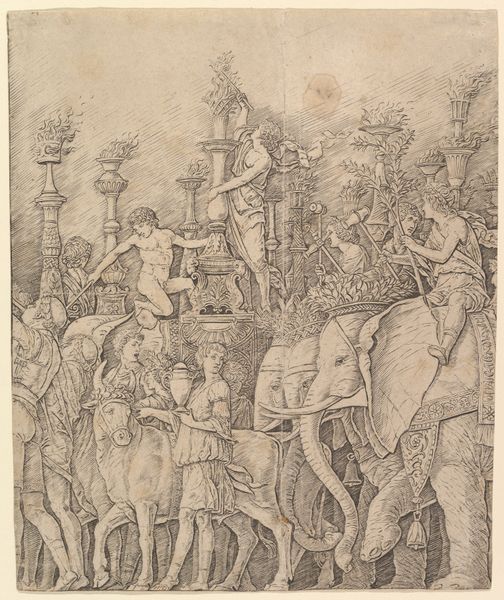

Triumphs of Julius Caesar: Canvas No. V c. 18th century

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, paper, ink, pen, charcoal

#

drawing

# print

#

landscape

#

classical-realism

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

paper

#

romanesque

#

ink

#

pen

#

charcoal

#

history-painting

Dimensions: 371 × 377 mm

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have "Triumphs of Julius Caesar: Canvas No. V," a work tracing back to the 18th century and currently residing at the Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: Immediately striking is the sort of muted, dreamlike quality. The parade almost feels…ghostly. It also reads to me as incredibly male-dominated, both the labor and the figures portrayed in supposed glory. Curator: Yes, it’s attributed to Andrea Mantegna and renders, in pen, ink, and charcoal on paper, a very deliberate imagining of classical antiquity, particularly the performative aspects of power. These “triumphs” were carefully staged events meant to solidify the ruler's image. Editor: Right, because what is triumph without an audience, without the right kind of messaging? This wasn’t about accurate depiction; it's carefully crafted propaganda. What gets depicted—and just as crucially, *who*—says everything about the society. And here, it looks like conquered people, presumably rendered as enslaved persons, were involved. Curator: Exactly. We must recognize Mantegna—and whoever produced this drawing in response— operated within a specific social structure, one with distinct views on class, gender, and authority. Reproducing Caesar's triumph, they're not just illustrating history; they are, consciously or not, participating in a continuing legacy of empire and conquest. Editor: Look at the elaborate ornamentation of the elephants. It is, in many ways, aesthetic violence—transforming living creatures into spectacle and, literally, beasts of burden in the service of power. This image speaks volumes about the systems in play, not just historically, but continuing into today, around labor, othering, and spectacularization. Curator: The original purpose was very much tied to projecting wealth and power, creating a historical narrative to support present-day rule. Museums are now reconsidering such problematic historical representations. Editor: Absolutely. Approaching art like this requires engaging critically, contextualizing it within power dynamics, and encouraging broader discussions about history, representation, and their implications today. Curator: Understanding the intent behind this piece, its relationship to its social context, helps us confront these questions, challenge assumptions, and understand the historical continuity that created our own world. Editor: Ultimately, an artwork like this, if unpacked thoughtfully, is less about what it literally shows and more about what it suggests, reinforces, and helps us undo.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.