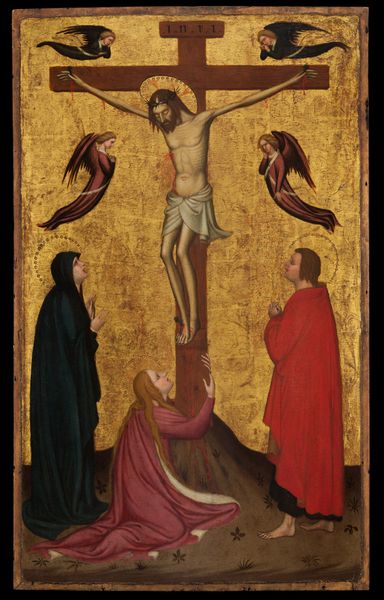

panel, tempera, painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

medieval

#

panel

#

tempera

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

gothic

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

form

#

oil painting

#

crucifixion

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

virgin-mary

#

realism

#

angel

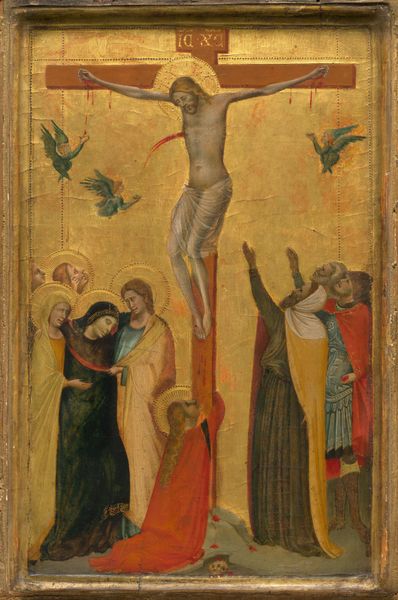

Dimensions: 54 1/8 x 32 1/4 in. (137.5 x 81.9 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

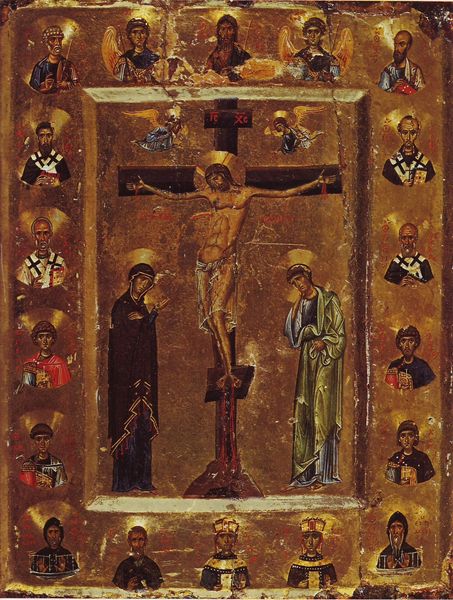

Editor: Here we have "The Crucifixion," an oil and tempera on panel created between 1360 and 1370 by Andrea di Cione, also known as Orcagna. Looking at it, I’m immediately struck by the way the golden background emphasizes the figures and makes the scene feel both dramatic and strangely detached. What catches your eye when you look at this piece? Curator: The dominance of gold, as you point out, is critical. It’s not merely decorative; it signifies the divine and positions this scene within a theological framework. Ask yourself, what socio-political function did this image serve at the time? Think about the power of the Church in the 14th century. Orcagna’s "Crucifixion" wasn't just about religious devotion, but also about reinforcing religious doctrine. Editor: So, it's about authority as much as faith? I guess the intense emotion shown in the faces surrounding the cross contrasts sharply with the rigid formality, creating a kind of visual tension. Curator: Precisely. Note how the figures of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the angels are presented within a complex system of patronage and viewership. These images were deeply enmeshed in the social fabric. This wasn't passive observation, but an active participation in a system that governed life. What effect might the idealized, almost serene depiction of Christ have had on viewers confronting daily hardships like the plague or poverty? Editor: It’s like offering a promise of otherworldly peace and redemption despite the earthly suffering surrounding them. The details in the smaller panels depicting saints reinforce this connection. This makes me consider the communal experience this artwork would have fostered. Curator: Exactly. These artworks were very effective in medieval and early Renaissance society. So what happens to such an artwork once it enters a museum setting, like here at The Met? Editor: That’s a fascinating point. Being in a museum now, it loses some of its original socio-political punch and becomes an aesthetic object. That’s a powerful shift. Curator: Indeed. Recognizing the original context illuminates its lasting power but also forces us to confront how art’s meaning changes over time, within changing political and social spheres. Editor: Thanks, I now see the image with renewed eyes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.