Copyright: Public domain

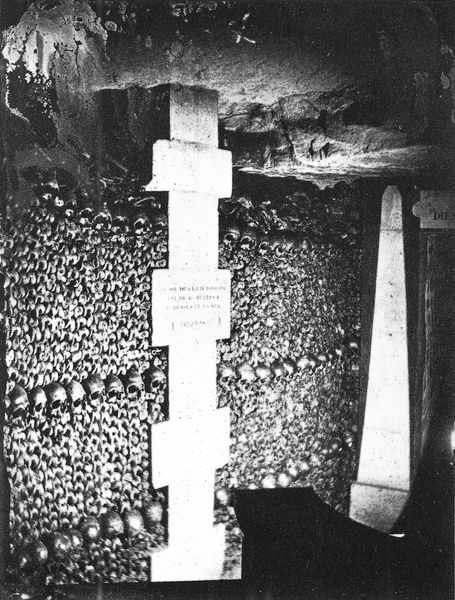

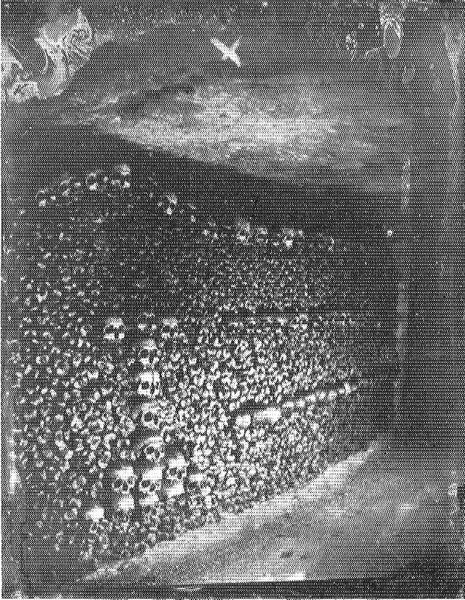

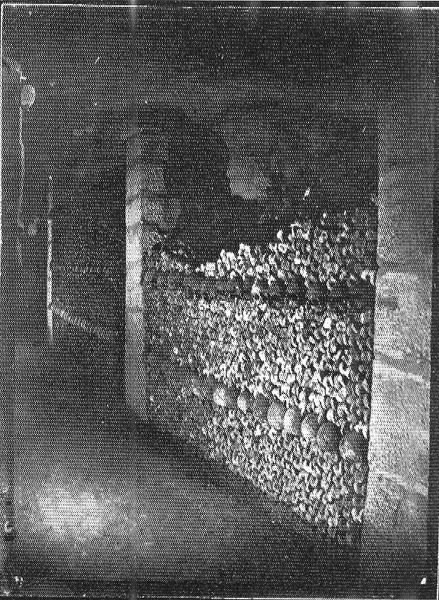

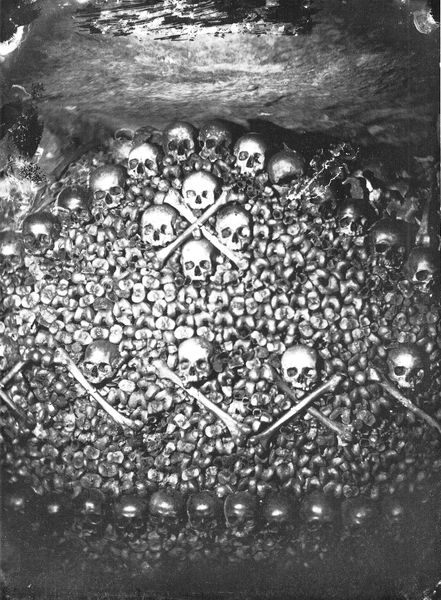

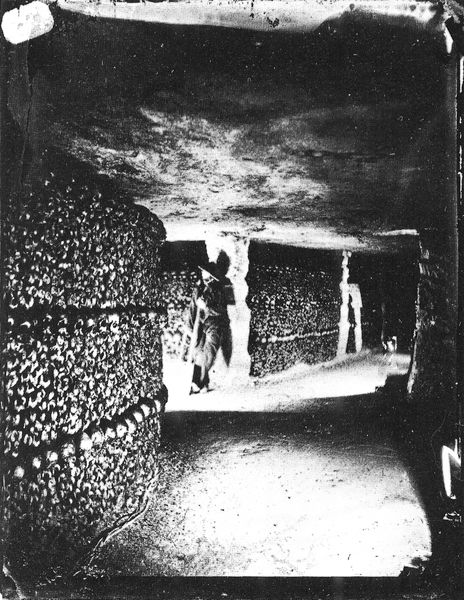

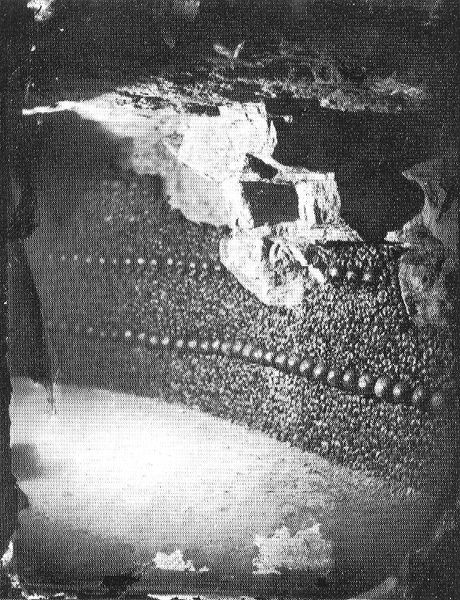

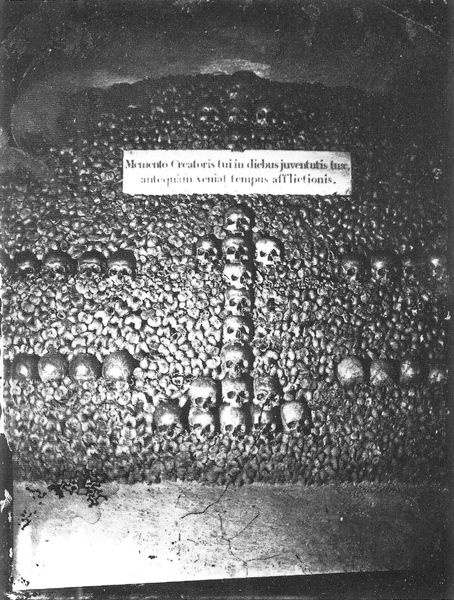

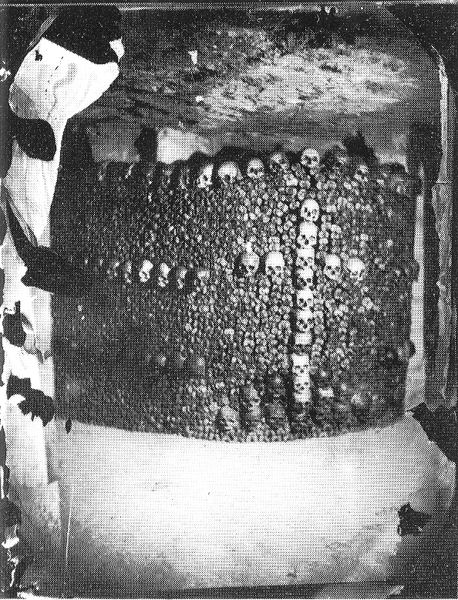

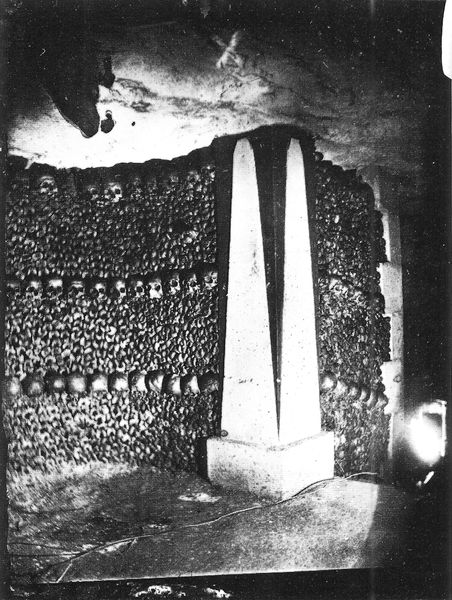

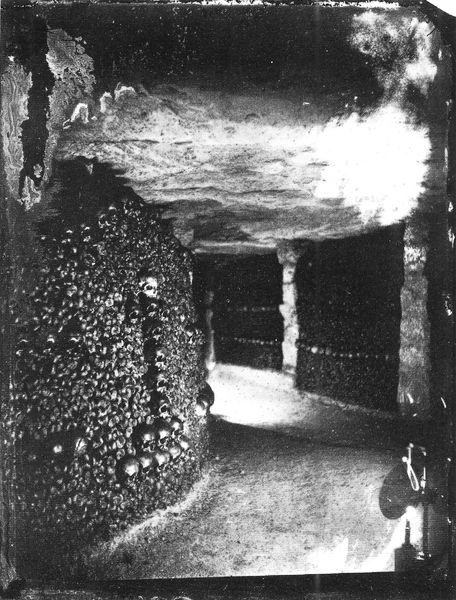

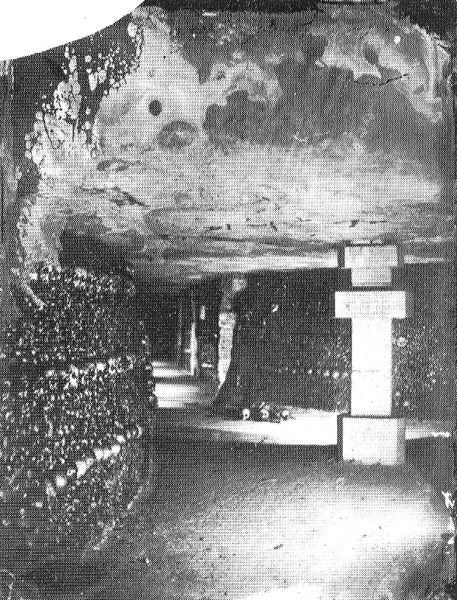

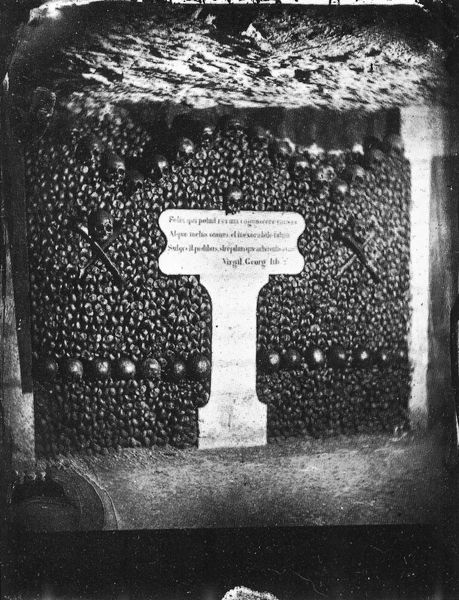

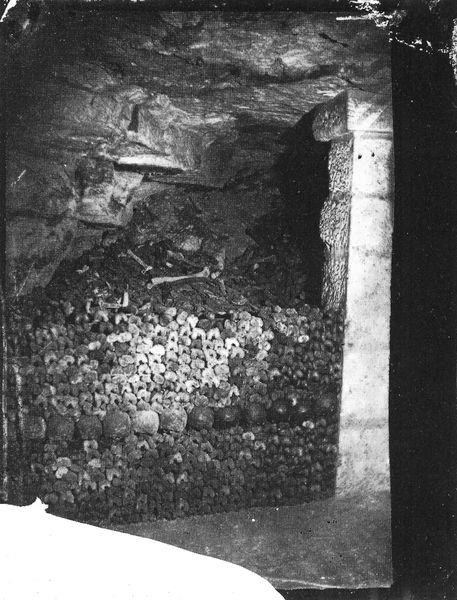

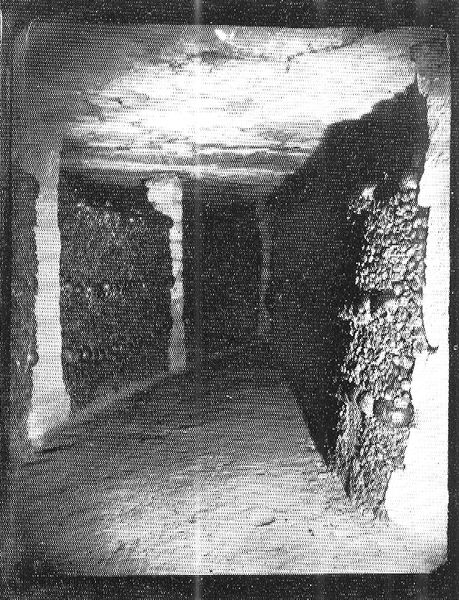

Curator: Good morning, I am keen to discuss Félix Nadar’s gelatin-silver print, "Catacombes de Paris," taken around 1861. It presents a stark scene from within the Parisian catacombs. Editor: My initial reaction is one of intense fascination. The somber arrangement of bones, contrasted against the stone cross, creates a compelling, unsettling tableau. Curator: The composition is carefully structured. Notice how Nadar uses light and shadow to draw the eye across the grid like patterns of stacked skulls, then directs focus with geometric shapes onto the right. It's about controlling space within the picture plane and about visual relationships. Editor: I'm struck more by the physical act, the labour involved, in both creating and capturing this image. Think of the workers exhuming the bones and arranging them decoratively, then Nadar's own presence down there, maneuvering bulky equipment, experimenting with artificial light. The physical materiality speaks of death but also production. Curator: Absolutely. And there's a semiotic play here, a discourse. The skull, obviously, has connotations of mortality, it signifies transience, of vanitas. Juxtaposed against the Christian symbol of the cross. A representation, really, about finding spirituality and meaning in the face of mortality. Editor: Exactly, yet that materiality extends to the very bones themselves. These aren’t mere symbols but remains – fragments of lives lived and reduced to anonymous building blocks. The Romantic ideal, perhaps, filtered through the cold pragmatism of industrialization and urban planning; a mass grave curated for both morbid curiosity and logistical necessity. Curator: We mustn't overlook the broader historical painting context. Here the historical moment of Paris is being reconfigured through photographs of death and a past both seen and unseen. Nadar makes the political act of building infrastructure almost invisible here. Editor: Yes, and maybe that erasure underscores something darker – how the city both honors and hides its past struggles in those ossuaries. The contrast with Nadar’s portraiture above ground could not be starker. The stark light used is key here to focus your attention and create something akin to historical painting. Curator: Nadar understood implicitly how to work through complex compositions to generate something evocative. And what this particular approach shows us of light, history and pictorial control, is quite fascinating. Editor: It pushes me to reconsider what it truly means to witness history, who constructs the images we deem “important” versus those laboring to make that witnessing possible, from material production to spiritual revelation, all captured through the unique means of gelatin silver printing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.