photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

sculpture

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

monochrome photography

#

history-painting

#

monochrome

#

monochrome

Copyright: Public domain

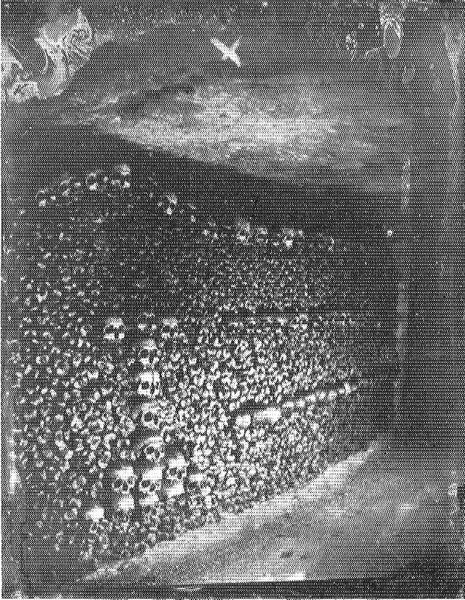

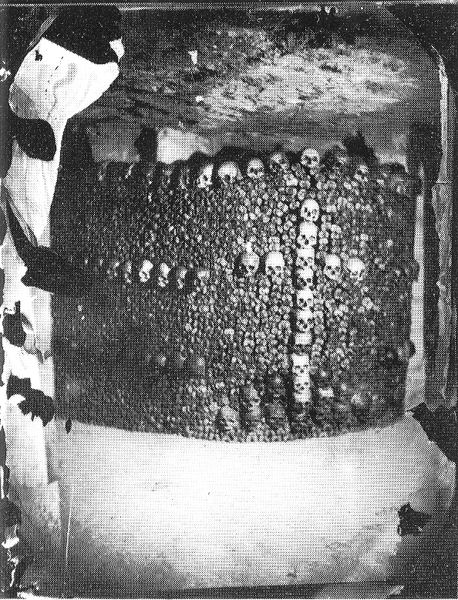

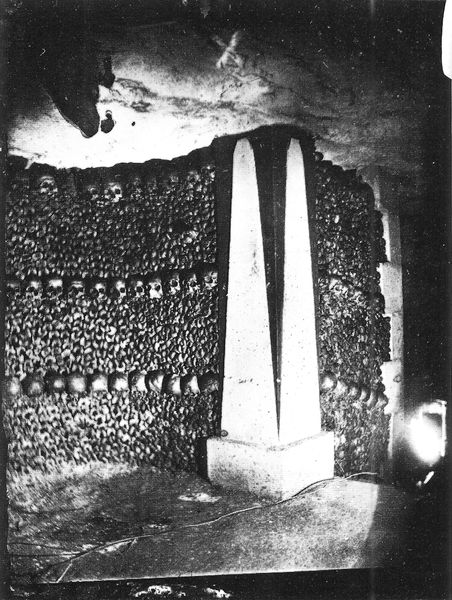

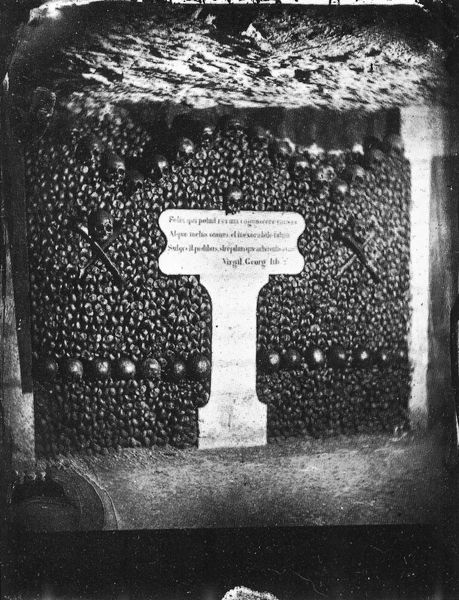

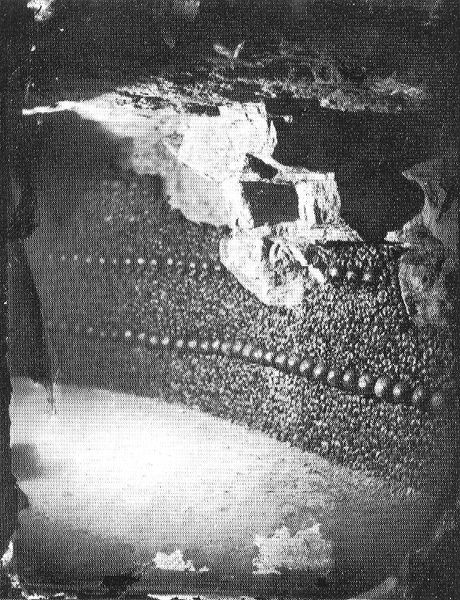

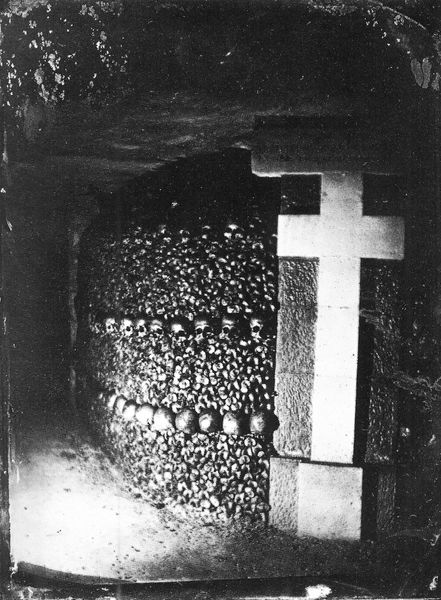

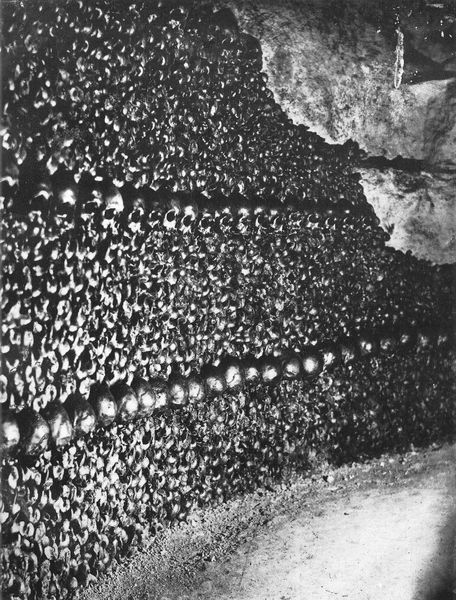

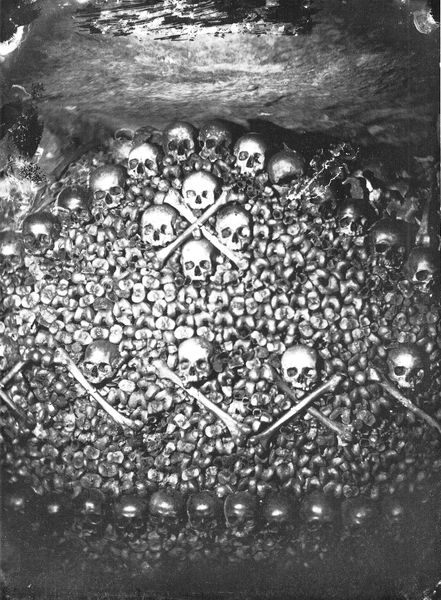

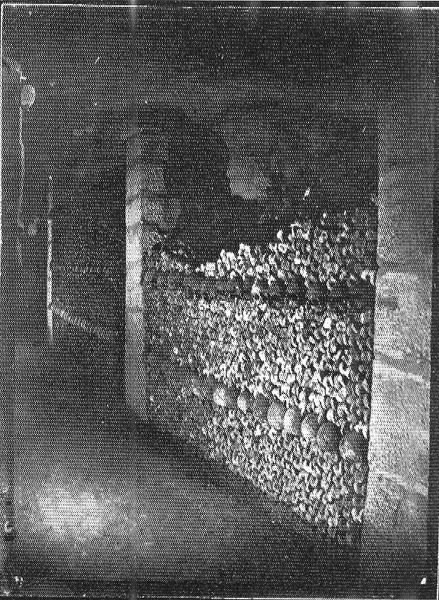

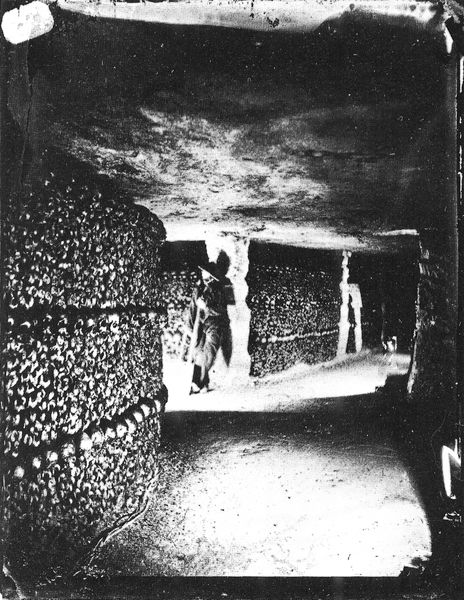

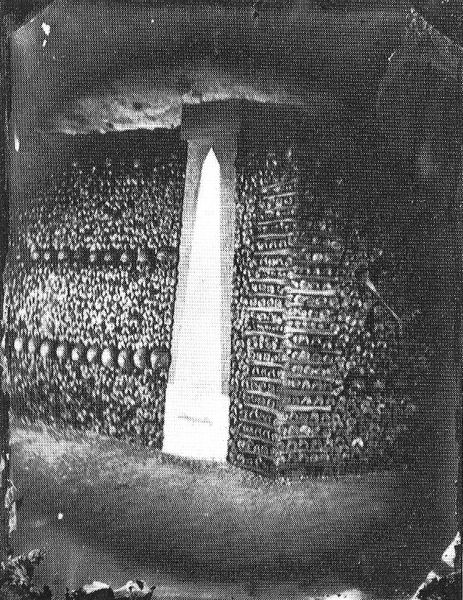

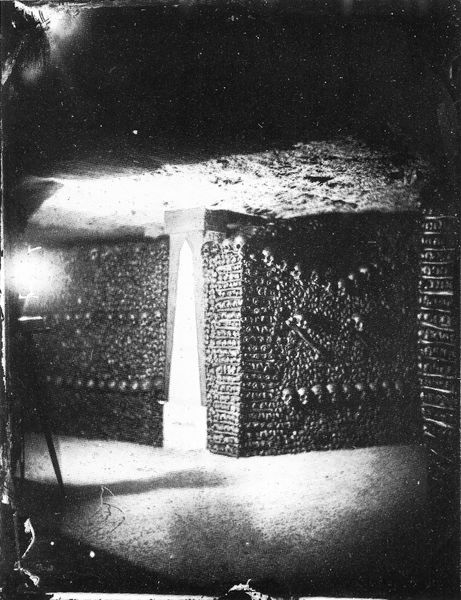

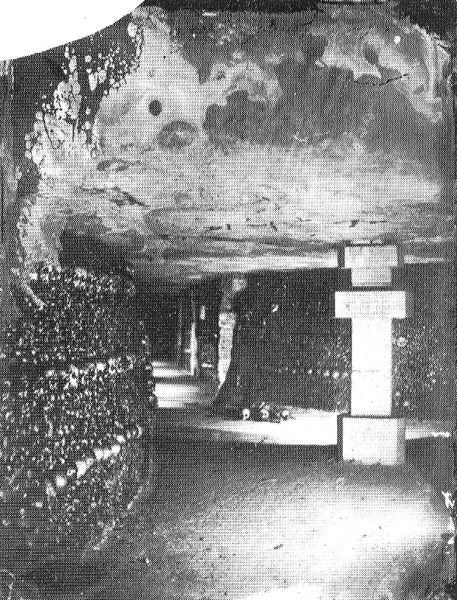

Curator: Oh, wow. It's like a gothic poem solidified into a visual experience. Editor: Indeed. This is Felix Nadar’s “Catacombes De Paris,” a gelatin silver print from 1861. What’s striking is the confluence of art, history, and the stark realities of human mortality it captures. Curator: Mortality is definitely the right word. There’s something deeply unsettling and strangely beautiful about it, like looking at a well-organized memento mori on a massive scale. It also has the strange beauty of those symmetrical cemeteries they have here, I recall seeing a similar one in Père Lachaise. Is this that? Editor: These are subterranean ossuaries holding the remains of more than six million people, yes. The overcrowding of Parisian cemeteries at the time made their existence vital. Note the attempt at formal organization here, though—almost a perverse, unsettling act of civilization within the dark depths. Curator: A cross, if I am seeing it well, shaped by human skulls is very on point, very on brand with what one could expect from catacombs. I like this dark humor. I mean...I also shudder. Is this kind of sculptural arrangement part of why it's sometimes categorized as history painting, even though it’s photography? Editor: Precisely. Photography, particularly in Nadar’s hands, elevated itself to the realm of grand historical narrative. Consider the interplay between light and shadow; Nadar pioneers artificial lighting in this environment. He coaxes drama out of the lifeless remains, inviting us to consider universal themes through this specific lens. The monochromatic choice simplifies forms down to their barest emotional context. Curator: So it strips away any potential glamour or distraction. Does that Latin inscription read “Remember your Creator in the days of your youth, before the time of trouble comes?" Which feels... pretty pertinent! In this photograph the idea that this could happen to anyone and that they too will end up down in the catacombs seems imminent, close and personal. And not abstract or impersonal, right? Editor: I concur. Nadar captures not only a space but also an existential condition—the great equalizer of death—rendered in meticulous detail with an awareness of artistic precedent, inviting all into a shared, reflective encounter. Curator: It is the great question, isn't it. Wonderfully thought-provoking work. Editor: Agreed. A morbid reminder but beautifully achieved.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.