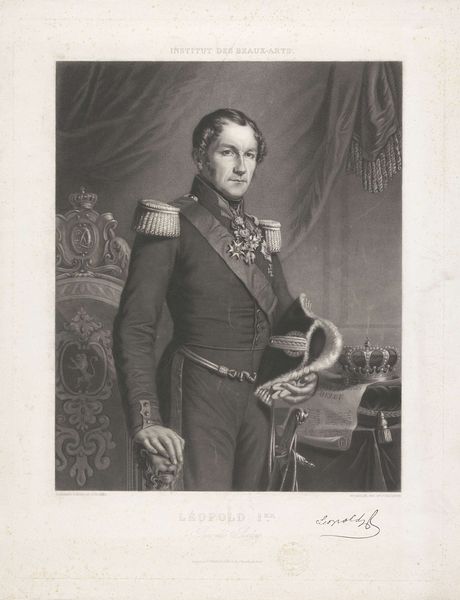

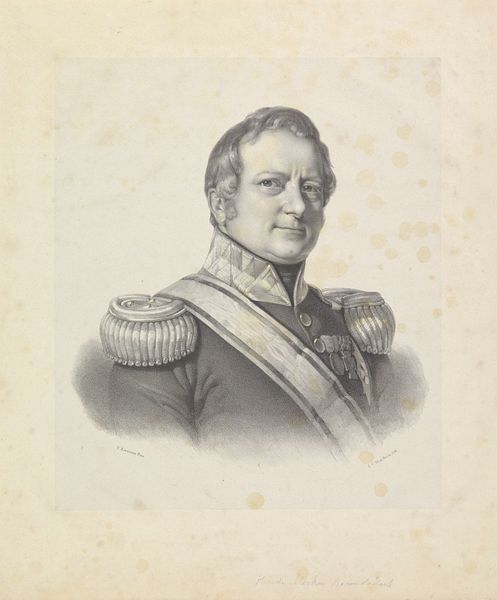

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

historical photography

#

19th century

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 106 mm, width 70 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Carl Mayer’s portrait of Leopold I, King of the Belgians, made sometime between 1831 and 1865. It's an engraving, and the detail is really striking. There’s such an imposing, almost stern quality to the King’s gaze. What do you see when you look at this portrait? Curator: What I see is a deliberate construction of power, typical of 19th-century portraiture, but ripe for deconstruction. The meticulous detail you mentioned is not just about artistic skill, but about projecting authority and legitimacy. Consider the context: Leopold I, a German prince, becomes King of a newly independent Belgium after a revolution. Editor: So the portrait is about establishing his image, creating a brand, in a way? Curator: Precisely! Think about the visual language being used. He is adorned with medals and sashes. Mayer highlights the trappings of monarchy in a relatively new nation-state. What does this choice of imagery say about anxieties of legitimacy, about solidifying a relatively unstable position of power? The Realist style gives an aura of veracity, as if we are getting an objective view. How objective can a portrait of a king really be? Editor: That makes me see the portrait completely differently. The apparent realism feels like a way of naturalizing power, of presenting it as inevitable rather than constructed. Curator: Exactly. It makes you question who this image serves, and whose narratives it silences. Can we look beyond this official representation? Whose stories are absent from this picture? What are the potential implications? Editor: I never thought about portraits that way before. It's like there are hidden arguments embedded in them. Thanks for that different view! Curator: My pleasure! The politics of representation are always at play. Looking at historical context lets us see how identities and authority were manufactured and sustained, then and now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.