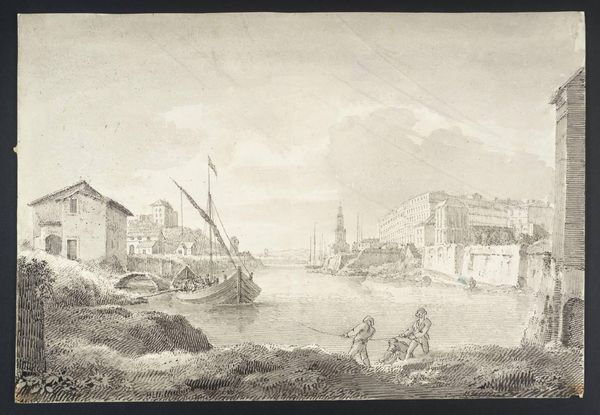

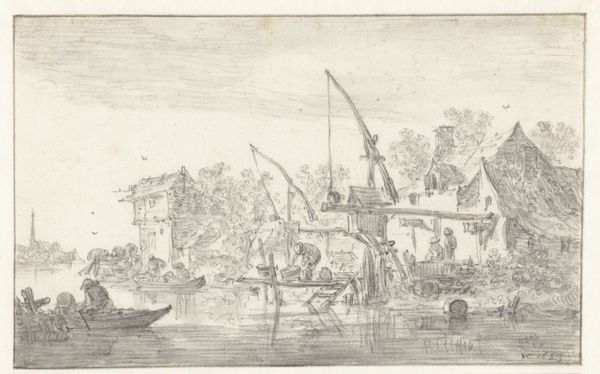

drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

pencil

#

cityscape

#

realism

Dimensions: height 264 mm, width 390 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Jacob van der Ulft’s “View of the Castle of Civitavecchia,” a pencil and pen drawing dating from around 1660 to 1689. Editor: My first impression? It’s airy, almost translucent. The light pencil strokes give it a dreamlike quality, as if the castle and the bustling port exist just beyond our grasp, a half-remembered scene. Curator: That ethereal quality likely comes from the medium itself. Van der Ulft, while known for his paintings of imaginary landscapes, often used drawings like this one for preparatory studies or as independent works for collectors interested in topographical views. The Dutch Golden Age saw a surge in demand for images of both local and foreign locations. Editor: I’m struck by the figures in the foreground. They're rendered with a degree of detail that almost humanizes the scene. But at the same time, their anonymity speaks to a certain power dynamic—the fortress and the state versus the individual. Who are these people in relation to the Castle itself? Curator: The figures absolutely contextualize the drawing. Civitavecchia, as a major port near Rome, played a significant role in papal trade and defense. By depicting the activity around the harbor, van der Ulft highlights the castle's function within the broader economic and political landscape of the Papal States. Editor: It raises a number of interesting questions, about empire, trade and mobility. How do social class and gender inform our reading of who gets to enter such place. The work seems to emphasize both the fortress and a site for cross-cultural interactions in trade and commerce. The sketch's emphasis on small details gives texture to the relationship between global commerce and individual labor. Curator: Exactly. Moreover, the very act of depicting Civitavecchia, an Italian port city, reveals the Dutch Republic’s interest in the Mediterranean and its own burgeoning maritime power. Van der Ulft, though he likely never visited Italy, drew upon existing prints and descriptions to construct his scene, which speaks volumes about the role of imagery in shaping perceptions of distant lands. Editor: It's fascinating how this drawing, seemingly so straightforward, becomes a window onto the complex intersections of trade, power, and representation of the period. And with respect to our current moment, questions about citizenship and social order within heavily monitored national borders emerge in this older port scene, revealing long histories. Curator: Indeed. And van der Ulft’s “View of the Castle of Civitavecchia” reminds us that even seemingly simple depictions of landscapes can offer rich insights into the social, cultural, and political dynamics of their time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.