print, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 577 mm, width 508 mm, height 580 mm, width 513 mm, height 581 mm, width 509 mm, height 583 mm, width 510 mm, height 583 mm, width 495 mm, height 580 mm, width 490 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

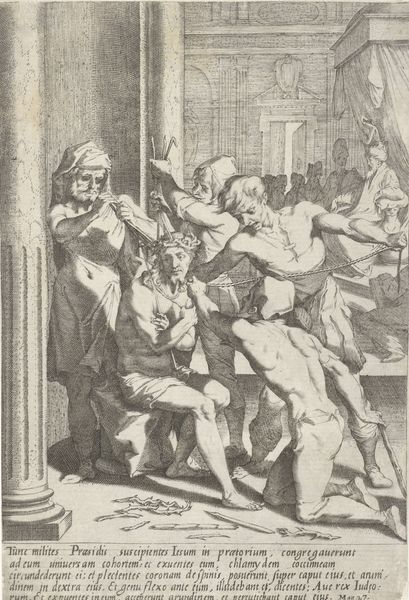

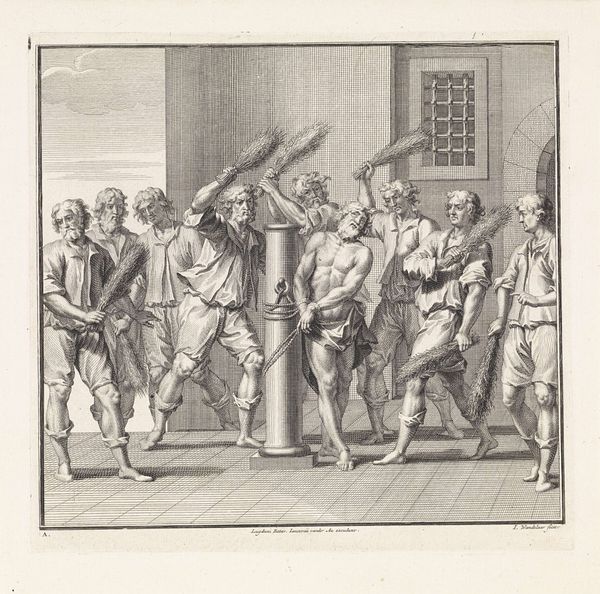

Curator: This is "The Flagellation of Christ", an engraving produced sometime between 1625 and 1670, attributed to Mattheus Borrekens. It's currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It’s immediately striking in its brutal detail, the almost theatrical staging. Look at the sharp lines, the intense contrasts – it really emphasizes the violence of the scene. You can almost feel the sting. Curator: Exactly. Consider the context. Printmaking in the 17th century was crucial for disseminating religious imagery to a wide audience. Prints like these would have been affordable, allowing even poorer members of society to contemplate such iconic moments. Editor: And what a tool it must have been. An inexpensive way to promote doctrine through mass production. It highlights how easily narratives were reproduced through material culture. What I notice are the disparate qualities and textures, look at the executioners' crude weaponry – whips, switches, juxtaposed against Christ’s vulnerable, exposed flesh. Curator: The theatricality also owes a debt to the Baroque style. Dramatic composition, heightened emotion. Look at how Borrekens stages the scene, with the figures arranged almost as if they are on a stage, columns giving scale and classical gravitas while creating spatial divisions. Editor: Notice how the engraver manages to give mass and volume through this very involved layering technique, giving density to these tormentors in comparison to the relative bareness of Jesus. What are we supposed to glean about social stratifications through that intentional dichotomy of making? Curator: One interpretation is of Christ as the figure of hope for a socially disparate audience. Consider too the politics inherent to image making at the time. Remember, in the Dutch Republic religious representation was a loaded subject after the Reformation. Images served social functions of all sorts beyond simply representing a Biblical passage. Editor: And by turning this sacred act of religious iconography into a tangible, material product like a print, the narrative becomes, at once, a token of devotion and also an element deeply rooted in commercial exchange, which certainly changes the original intention. Curator: A fascinating and very insightful way to put it, it reminds us of the complex tapestry of forces at play during its making and subsequent distribution and consumption. Editor: A visceral rendering; one really feels both the weight of materials and their capacity to tell familiar stories anew.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.