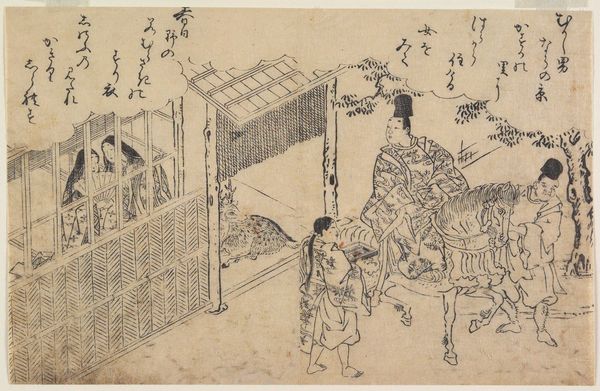

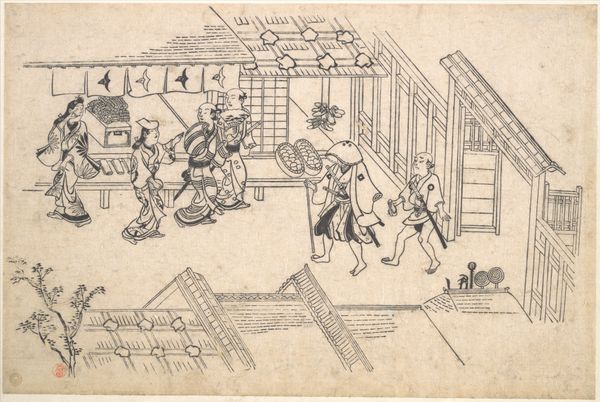

A Passing Palanquin, from the series "Scenes of Flower-viewing at Ueno (Ueno hanami no tei)" c. 1681 - 1684

0:00

0:00

print, paper, ink, woodcut

#

narrative-art

# print

#

pen sketch

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

ukiyo-e

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

woodcut

Dimensions: 27.1 × 40.9 cm

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: There’s a kind of serene simplicity to this piece that draws you in. It feels effortless, even though I know woodcuts are anything but. Editor: That's a lovely sentiment. We’re looking at "A Passing Palanquin," part of the "Scenes of Flower-viewing at Ueno" series by Hishikawa Moronobu, created around 1681 to 1684. You can see it here at the Art Institute of Chicago. Immediately, the palanquin takes my attention – a mobile room if you will – the horizontals giving the impression of a building, while the whole scene seems almost caught between inside and outside worlds. Curator: It does have that liminal quality! And those figures carrying the palanquin look properly burdened but not defeated. It’s like they’re part of a little performance, part labor, part theatrical transport. Is that figure peeking out of the palanquin observing her audience? The woman is seated facing us! Editor: Ukiyo-e prints often serve as windows into cultural moments, especially around fashion and social hierarchy. Consider how the palanquin visually isolates its passenger – a signifier of status. And then the monk, at right, set apart with his robes and staff, the cherry blossoms adding another layer, a marker of time and fleeting beauty... All these details tell us about values in that society. Curator: Yes, fleeting beauty! And social codes, totally. It's like glimpsing a little secret garden, you know? That almost feels rebellious considering its traditional medium. It is like you are viewing another reality as well, a constructed artificial version of space and transport that reflects cultural biases. It must have seemed very provocative at the time. Editor: Well, rebellion may be too strong a word – it served more as a stylized reflection, a commercial rendering that helped to create and satisfy interest in a particular lifestyle, and disseminate popular aesthetics. I’m particularly intrigued by that diagonal line leading to what appears to be other people on the background far left: how has this narrative changed, become lost or evolved into something new today? It still resonates, though. Curator: Absolutely. It has this timeless appeal, because we keep circling around these questions of what status and belonging mean, whether it’s palanquins or…status updates. Editor: A fitting parallel. After spending this time, I notice more, feel more complexity in Moronobu’s vision here. Curator: Me too. What felt simple now hums with possibilities.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.