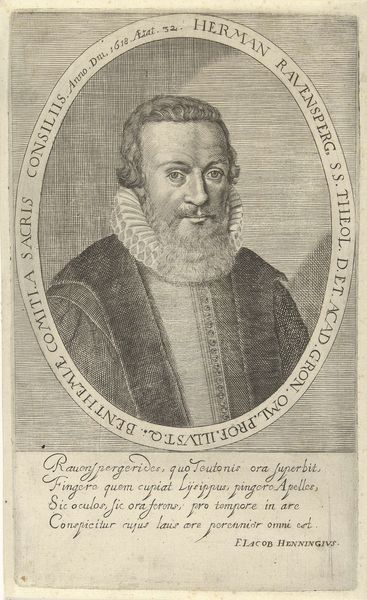

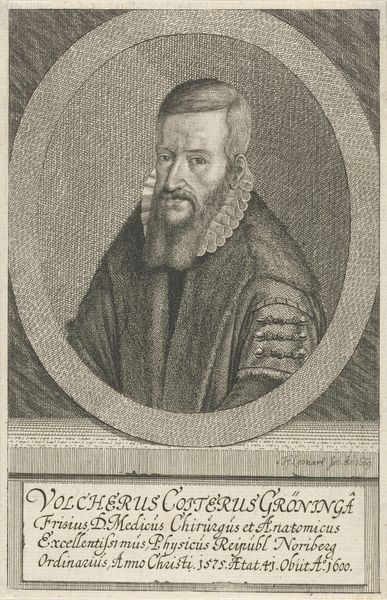

print, paper, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

paper

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 186 mm, width 126 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Gerrit Muntinck's 1618 engraving, "Portret van Herman Ravensperger." The print depicts a stern-looking gentleman, framed in an oval. Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by the meticulous detail! Look at the ruff—how many hours of labor went into rendering those tiny pleats? It feels almost like an exercise in virtuosic printing more than a portrait. Curator: Yes, the technique is remarkable. There's an almost hypnotic quality in the cross-hatching. You feel the weight and deliberation involved. But let’s not forget the sitter, Ravensperger, a theologian, and professor in Groningen. His presence seems both imposing and a little weary. Editor: Weary indeed! Consider the context. The burgeoning merchant class sought legitimization, often commissioning art that depicted themselves surrounded by emblems of learning and status. The printing of the artwork makes multiples that could be distributed to other universities and scholarly institutions as proof of intellectual position. Ravensperger's pose—hand raised, open book—are less spontaneous expressions of intellect, and more a conscious crafting of a public persona meant to be reproduced ad infinitum. The act of printing, then, solidifies status and disseminates ideology. Curator: I see your point. And yet, there’s a certain psychological depth that transcends mere propaganda. I’m drawn to his eyes. Despite the formality, I see a hint of melancholy, as if he carries the weight of knowledge and responsibility on his shoulders. The poem printed below his image, while undoubtedly celebratory, does not give as much insight as his features do. Editor: Melancholy? Perhaps. Or perhaps just the strain of maintaining an image. Regardless, this engraving isn’t just a picture—it's a manufactured representation, meant to be consumed and disseminated in very particular ways. Even the seemingly decorative elements contribute to that material reality, driving forward a specific vision. The labor needed to render the tiny pleats as well as print all the text is astonishing to imagine. Curator: I'm so captured by the sense of dedication infused in the piece: in Muntinck’s meticulous work but also in the sitter's learned attitude. And it feels almost like you and I are also working diligently to find out about it, after so many years. Editor: Absolutely! And that speaks volumes about the endurance of art's social role—to capture, reflect, and project values, even as the materials and techniques evolve.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.